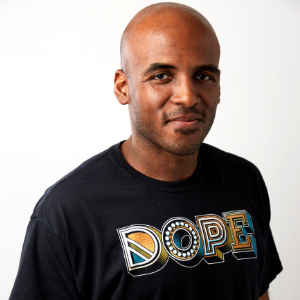

Kevin Tufts is the real deal when it comes to tech and design. With over two decades of experience working across a number of companies in the Bay Area — Lyft, SendGrid, and Twilio, to name a few — he’s now a product designer at Meta working on their Creation team. So believe me, we had a LOT to talk about.

Our conversation begin with a look at the current climate inside Meta (pre-Threads, FYI), and he gave some thoughts on where the company is going as it approaches its 20th anniversary. From there, Kevin talked about his path to becoming a product designer, and we took a trip down memory lane recalling the early days of web design and what it was like working during such rapidly changing times. He also spoke on what he loves about product design now, and how he wants to help the next generation of designers through mentorship.

Kevin’s secrets to success are simple: seize opportunities for growth where you can, embrace collaboration, and remain flexible. Now that’s something I think we could all take to heart!

Maurice Cherry:

All right, so tell us who you are and what you do.

Kevin Tufts:

I am Kevin Tufts. I am a product designer currently working at Facebook, and I live in San Jose, California.

Maurice Cherry:

How has this year been treating you so far?

Kevin Tufts:

I’d say personally the year has been pretty good. I am grateful to be employed and obviously you’ve seen in the media that Meta has had several waves of layoffs, unfortunately. So all things considered, I feel pretty grateful. Feel pretty good, but a little anxious. I’m human, so it’s definitely some wild times not just within Meta, but the tech ecosystem as a whole.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Do you have any plans for the summer?

Kevin Tufts:

Plans for the summer are going to be pretty chill. So one of my side hobbies is I’m an avid cyclist, so I’ve been doing bike events from beginning of April up until just a couple of weeks ago. So this summer I think I’m just going to chill, stay local and got some family stuff happening. I got some folks coming into town, so should be hopefully a quiet summer.

Maurice Cherry:

Nice. That’s good. Is there anything in particular that you want to try to accomplish this year, like for the rest of the year?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, there’s some kind of like more career-oriented things that I want to sharpen up on and that’s with mentorship and maybe doing more design oriented workshops where I’m teaching kids from different backgrounds but mostly from people of color how to use design tools and how to get into product design as a whole.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, I think that’s a really good thing, especially now when I’d say I feel like over the past two or three years we’ve started to see a lot of the younger generation, like Gen Z and younger are starting to look at tech more as a viable opportunity for them to go into for their career. So that’s a good thing. I hope you get a chance to do that.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, looking forward to there’s a couple of avenues and programs that I’ve been working with here in the Bay Area that’s been awesome. So yeah, there’s some big things on the horizon for me personally.

Maurice Cherry:

Nice. Talk to me about the work that you’re doing at Facebook. Like, are you working on a specific product there?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, mostly working within what’s called Creation, and that’s the organization that handles a lot of our creation tools like Reels and Stories. And so for me, a lot of my work swirls around Stories, so I get to touch everything from the gallery to the Stories composer, just the experience itself, which has been pretty cool. And then I also work across Facebook, Lite, iOS and Android. And I call that out because most people that are listening, that are here within the US. May not be aware that we have such an app called Facebook Lite, but it’s a stripped-down version of the app that runs on Android and it’s a popular app in kind of like more developing nations.

Maurice Cherry:

So like if you’re using, say, like, I know there’s this terminology of a dumb phone as opposed to like a smartphone, but like a phone that’s not maybe always connected to the Internet.

Kevin Tufts:

You got it. Yeah, you nailed it. So there’s different flavors of that where you can go into low data mode, and then you’ll see almost just a very plain Jane. Just a few images and some text, just a stripped down version of the core app.

Maurice Cherry:

What does your team look like that you work with?

Kevin Tufts:

Team is pretty big, so within the organization there are different pillars that handle different aspects of the experience. I’m on the Creation Growth team, so we run tons of design experiments. It’s a really fast moving, fast paced.org, can be challenging, but really fun because you get to try all types of different unique design directions that you wouldn’t necessarily try in other product spaces around Meta. And we have quite a number of designers as well.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, what does a regular day kind of look like for you? Are you working remotely? Are you back in the office now? What does that look like?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, I’m working remotely, and just recently, like most companies in the Bay, we have a new return to office policy. So a lot of us will be continuing to work remotely. And some of us that live here in the Bay are going to be going in three days a week.

Maurice Cherry:

So you would have to be going into the Menlo Park office then?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, that’s my closest office.

Maurice Cherry:

I’m trying to place the Bay geography. How far away is that from where you’re at in San Jose?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, it’s about a 20 minute drive. 25 minutes? I mean, it takes a while because of traffic.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Okay, that’s not that bad. That’s not that bad at all. Yeah. The last time I was in San Francisco was in God. Oh, that was 2016, actually was 2016. I spoke at Facebook, and I remember it took…oh, wow. I think it took an hour to get from San Francisco to Menlo Park. And I was thinking, “people make this commute every day. This is a lot.”

Kevin Tufts:

That sounds great compared to doing like an hour and a half or two hours if there’s an accident.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. I want to approach this part of the conversation rather gingerly. I feel like there’s a third rail that I really don’t want to touch with regards to Facebook. But what’s the mood like there right now? I mean, as you mentioned, they’ve been in the news recently because of conversations around the metaverse. The Meta Quest 3 just dropped fairly recently, and then right after that, Apple dropped their AR headset. Yeah. What’s the mood like at Facebook overall?

Kevin Tufts:

I think because of the frequency of the layoffs, you know, we went into the end of last year with the first big wave, and then we just had the two more recent ones. People, they seem to be resilient, but a lot of us are kind of reserved and really just a little numb because all this stuff has been in such close succession, right. So ultimately everyone is just kind of moving forward and performing their duties as they always would. I think a lot of us are just trying to like, ride this out because we know that it’s going to be challenging for at least quite a few number of months before the dust truly settles. After every large layoff at any company, then there’s always the trimmers that you experience, right, because you’ll have a series of reorgs, so then you have to ride those waves. So that’s kind of where we are right now. But for the most part, everyone is pushing forward and we’re now into roadmap planning season. So it’s like our minds are occupied with just trying to plan for the next half.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, it can be a very odd place to still work somewhere after a layoff. Sometimes you have I guess the best way to call this, or the best thing to call it, would be survivor’s guilt that you’re here when maybe a team member has left or someone else you knew at the company has left. And then especially when these kinds of things happen in succession like that, it can almost kind of feel a bit like you’re walking on eggshells, I guess.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, in some regards it’s exactly like that because this is also impacting our performance reviews, right. So a lot of us engineers as well, you’ve been working on a project or maybe you’ve been reordered. So now the work that you had going on, you had to drop it midstream to go pick up something else from someone else’s team. And yeah, it’s chaotic and so there’s the stress of like, hey, how is my performance review going to look? That’s just kind of like where we are. It’s like you can only worry about what you can control. And I guess we’ll cross that bridge when we all get there.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Now for those of us who have been online for a very long time, when I say that at least 20 years or so, we remember when Facebook launched. Facebook launched in the early 2000s, like 2003, 2004…I think right around that time. And we’re now about to come up on Facebook’s 20th anniversary, which is wild to think of for an Internet company. What do you think, like Facebook’s place is now in this kind of modern internet era that we’re in?

Kevin Tufts:

Well, obviously we’ve tried to well, I shouldn’t say try, but we’ve entered the VR space, so I don’t see that going away anytime soon. But I think what we’ll start to head is maybe putting more development and focus into AI things as everybody is sort of racing to get there wherever there is. So we may have more of a shift towards AI oriented experiences and less attention on the metaverse and then obviously just kind of moving forward with the ultimate goal of just having a totally connected planet. Right. And what I noticed between the US. And just working on things that will be tested in other countries is that here in the US. The way the media spins things is that Facebook’s dying. And it’s really just kind of how the media frames things. But it’s not. It’s like the popularity of the app hasn’t really dipped and it’s actually increasing outside of the U.S. market. And then within the U.S. market, there’s quite a number of unique things that I think we’re going to be able to latch onto and really just kind of like shock the general public.

Maurice Cherry:

Sort of reminds me of that saying about the reports of my death are greatly exaggerated or something like that. I think Mark Twain said that probably. I mean, with a company as big as Facebook that has a global reach like that. I get what you’re saying about the media, like tech media here or even the more mainstream outlets here will make it seem like, oh, Facebook is this big dying site. But Facebook is still the number one website in the world. And the world is a big place. It’s not just the U.S. I mean the U.S. media scene, the U.S. tech scene, et cetera. Facebook has not only just Facebook the social network, but Instagram and WhatsApp. And there’s other apps and things that are out there in the world that are heavily used. So to say that Facebook is dying feels kind of premature just because it has a reach that eclipses so many other products, so many other companies. It’s a lot bigger, I think, than we might think that it is based on what the media might say it is.

Kevin Tufts:

And we don’t think about a lot of the other sub-products. Right. We have Groups, which is the communities based product within the app. It’s extremely popular messenger. We’ve got our foot in so many different pools right now that it’s really just kind of like the media, the U.S. focused media that’s always basically picking on the company.

Maurice Cherry:

Right. And I mean, folks that have listened to this show for any period of time know I am not a Facebook fan. I’m not going to say I’m a Facebook hater, but you can’t knock the fact that Facebook has…it’s got its reach in a lot of different places across a lot of different products. And so just the social network itself is not the entirety of what Facebook is about.

Kevin Tufts:

That’s right.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah.

Kevin Tufts:

And I never thought that I would be working here. And now that I’ve been here almost three years, I could definitely see both sides of the coin, especially in terms of how the media positions things, but also rightfully so. We have a huge trust deficit that we’re continuing to try to improve. But it’s a hard mountain to climb, especially after the ways of layoffs that we’ve just seen. And some of the initiatives that the integrity teams have been cut. It’s tough, it takes time, and unfortunately things move faster than we can react to.

Maurice Cherry:

And some of those things are not even in Facebook’s control. Like the things that happen with workforce reduction and things, a ton of tech companies are doing that because they’re looking at the economy and seeing is the country going into a recession? So they’re trying to sort of react and pivot to what might happen. Like they’re trying to forecast the future here. So I think the longer a tech company and I’d say this is any company, not just tech companies, I think tech companies are specific in this case because they span so many different industries outside of just like software development or whatever. But the longer a tech company sticks around and almost feels like the more issues people will find with it one way or another, the companies are going to mess up. They’re going to inadvertently say something or inadvertently do something or maybe purposely say something or do something. Like the longer a tech company sticks around, it feels like…I’m a Math guy, so if I think of the duration of a tech company as like the limit of a function, it’s like as the limit approaches zero, or wherever the end of the company is, so to speak, things are going to happen. Things are just going to happen because social media influences culture and that influences technology. And so what might have been good five years ago is no longer good now. And if there’s one thing that’s going to be constant, it’s change. And I think when a tech company sticks around long enough, unfortunately they’re going to possibly come up on the short end of the stick when it relates to that.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, definitely. Absolutely.

Maurice Cherry:

Okay, enough pontificating on my part.

Kevin Tufts:

Love it.

Maurice Cherry:

Let’s turn this back on you. Let’s learn more about you and about your journey as a designer in tech. I want to really take this back to the beginning here. So talk to me about where you grew up.

Kevin Tufts:

So I was born in Cleveland, Ohio, the town and city known for LeBron James and it’s river catching on fire in the 1970s and terrible sports. Right. So that’s where I was born and right around the time I turned like eight or nine is when I moved to Southern California. So I have a big group of large group of family in Ohio, and then I have a family based in Southern California between the L.A. and Orange County area.

Maurice Cherry:

Okay. Were you exposed to a lot of design and technology growing up?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, so I was fortunate growing up that my dad, he was a computer guy, so I had a computer in the house growing up, which is completely rare, especially for the 1980s. So my dad, coming out of Vietnam, he was in a program that taught him how to work on mainframes. So when he got out of the military, he ended up landing a job in downtown Cleveland at one of the it’s really just kind of like a storage company, I guess you would say. I remember going to work with him and one computer took up the entire room and there’s these big reels and tapes. Yeah, I’ve always been exposed to tech stuff. And he was also like a big science fiction guy. And between having a computer in the house and then playing games at the arcade at the mall and just really watching science fiction flicks with him, there’s no surprise that I ended up doing what I’m doing today as for a career.

Maurice Cherry:

Now you went to Cleveland State University where you majored in design. I’m curious, before that, did you know that design was something that you really wanted to study?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah. So by the time I went to Cleveland State and it was a total fluke because I moved to Ohio for other reasons. And while I was there, it looked like I was going to stay for a few years. I just come from Southern California and went to Ohio and got myself enrolled in university because I wanted to make sure I didn’t have any huge lapse in time to get my education out of the way. By that time, I had already been doing freelance things. Like, I was pretty much thinking I was going to be a print designer around that time. So the late 90s, probably around like ’96, ’97 is when I had thought, “okay, yeah, I’ll get into graphic design.” At the time, I didn’t even know it was called graphic design, but I was always the kid at high school doing the hip-hop flyers, a lot of flyers for open mics raves. So it was like the starter. The inkling of me being coming to designer was back in those days doing like bootleg flyers.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, those early print days back then were something else. Just the amount of creativity that you had, even though the medium itself was sort of fairly limited, I mean, that was a lot of fun.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah. Do something like really weird on the computer and then print it out. And then I would take some markers and then do something on top of that so it’d be like this multimedia flyer thing. Cut stuff out, paste it on and then xerox it again like at Kinkos. All that kind of stuff. Using QuarkXpress.

Maurice Cherry:

Oh, man. QuarkXpress. I just had someone on recently and we were sort of talking about those early days with like PageMaker and Quark and trying to figure all that stuff out because I remember Quark specifically because I used that along with PageMaker to design my high school newspaper. And the instruction manual that it came with could choke a horse. That thing was huge.

Kevin Tufts:

And you had no one to read that stuff.

Maurice Cherry:

Nobody was reading through all that. This is way before online documentation. I mean, this thing came with a brick of an instruction manual that you had to go through. And I’m like, I have to know all of this just to use the software. It almost didn’t feel like it was worth it.

Kevin Tufts:

Right. Oh, wow.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, while you were in college, you were also a working designer too, is that right?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah. So I went to college, I was probably in my mid 20s, so basically I thought I had the world figured out because after high school, I didn’t go straight away to college. And that’s when a lot of my high school friends and people around me were just getting hired out of high school to just do HTML and build some wacky website. So I followed that path. And then when the.com bubble burst, it was a hefty smack in the face of reality. So that’s kind of like, what got me into Cleveland State. But by that time, yeah, I was working for E-Business Express, which is a web hosting company. So I was very fortunate. I was already kind of knowing my destiny, what I needed to do, where I wanted to go. And then I was also, like, in practice where other students in the class were just kind of like, figuring out what Illustrator is or Photoshop.

Maurice Cherry:

E-Business Express is like a quintessential 90s online business.

Kevin Tufts:

Right?

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Exactly. What kind of stuff were you doing there?

Kevin Tufts:

I started off as a Linux server admin, so I wasn’t even doing, like, design stuff. But what I was doing that was valuable was because it’s a web hosting company is now I understand how things work behind the scenes, like how websites function. So I had that foundation of, like, I guess you would say webmaster at that time. That’s what it was considered. But yeah, just understanding how DNS works for www, your web domain, registering names, taking servers offline, like, really heady stuff. But I enjoyed it. It fulfilled, like, a side of me that I really like to tinker and explore things, and just being a Linux admin that it did it for me. But then it also gave me access to kind of like host my own little microsites and really just enable certain things on the server that people just don’t have access to. Right. Or if you’re designing a website, you’re certainly not thinking about uploading things on the command line and just really kind of Star Trek stuff at that time. That’s how I treated it.

Maurice Cherry:

Well, I mean, also the thing back then is a lot of that stuff around web hosting was very opaque. Like, you almost had to be a command line or a terminal coder to know how to really get around, because the graphical user interface, or the GUI, I guess what we called it back then, like, the GUIs, were just not super user-friendly to that point. So you did have to know maybe how to telnet or how to or use a Linux command in order to change the permissions on a directory. Like you couldn’t just click a button or something to make that happen.

Kevin Tufts:

That is a great point. Yeah, in the early days it wasn’t for everyone. You definitely had to have some technical prowess in order to upload a file or to get your web address, like get it all working, pull up a page.

Maurice Cherry:

I remember I was in high school in like the late 90s, and I remember even doing FTP stuff and being told at the time…I think maybe one of my teachers that told me was like, “oh, so you’re hacking, you’re a hacker now.” I’m like, it’s not hacking, it’s just FTP. But because they don’t see any graphics, all they see is just code. Because you know, this was like right before The Matrix or right, Matrix came out in ’99. I remember because I was a freshman in college, it came out in ’99 and yeah, all that stuff about FTP and oh my God.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, it was crazy, right? It’s like the only context the common man had was like some science fiction movie and then you think about it…it’s really like quite simple stuff.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, in hindsight, when you look back at it, it definitely is simple stuff. But yeah, during that time, just knowing how to do some of that sort of stuff, like people thought you were like a magician or something. You can make a website, you can put a picture of yourself online. How do you do that? And even what does online mean? Because the concept of being online in the 90s, like mid to late 90s, is such a different thing than now because social media didn’t exist. So for you, do you remember what that time was like for you?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, it was a whole new world and it felt like there wasn’t much online to look at. But I do remember like in the early days you had to work hard to make friends. So forums were real big, the IRC channels, so forums and chats, so AIM or Instant Messenger, Yahoo Chat. I remember all those different worlds and rooms and just whatever your interest was, you would just go out into that forum or chat, find your folks and then it was just kind of like not even instant replies, especially in the forum. You go in there, you chatted up, and then maybe 24 hours later you got a response. A lot of that stuff was amazing. I remember downloading my first video and it was a clip of a race car. It was like a drag strip. It was a 30 second clip. And I think it took like an hour and a half, maybe even two hours for that 30 second clip to download so that I could watch it over my 56K or whatever the modem was at the time. But yeah, it was just such a cool adventure and tinkering around with HTML and doing all the corny stuff like making the animated tickers. It was the Wild, Wild West, and I loved every bit of it. But it definitely took some patience. And you had to work hard for anything that you wanted to do on the Net.

Maurice Cherry:

Going back to E-Business Express for a minute, I mean, you worked there for almost eight years. When you look back at that time, what do you remember the most?

Kevin Tufts:

I remember that it really helped me understand how the web functions and everything that’s needed for standing up a business. Because E-Business Express also specialized in helping medium, like small to medium sized businesses get set up online to sell. So it also gave me experience working within the realm of e-commerce. And then while working there, I worked there for eight years. And part of that was because the first few years I spent doing Linux admin stuff before I moved into becoming a full-blown just web designer for the company. So I’d switch roles, and the back end of my tenure there is what gave me experience with design, working with clients. So working more in, like, an agency style format is where I cut my teeth, as I guess you’d say, a traditional Web designer before moving into product.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, let’s talk about that shift. After E-Business Express, you’ve kind of started your career as a product designer at DotNetNuke, which now is known as DNN. How can I explain DotNetNuke? It’s a content management system. I have minimal experience with it. I worked with it briefly at WebMD and just thinking, like, how could someone make software so convoluted and confusing?

Kevin Tufts:

Well summarized.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Tell me about your time there.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, so the company is very unique because, as you said to CMS, and we had a lot of big government contracts, and there’s some educational institutions as well. And it was I’m trying to think of how to compare it maybe like a behemoth compared to WordPress. WordPress was really easy to get up and running. But there is a large community for Net Newt and primarily ran on Windows. So then you’ve got the IIS crowd of folks that are into it. So you got the engineer side, a lot of developers that supported the community. And then you also have the support side because there’s a lot of folks that were spinning up businesses around, like installations and helping you get up and running. On DNN, we also had those services as well. And then for me, it was awesome because it was my first foray into product thinking and product design. So when I worked at the company, we had, I think, three designers. Two of them were in marketing, I believe. And it’s just one product design person that did everything. It was like the jacket of all trades, but it. Was really cool. This is the first time getting experience with a design system where at that time we had a sticker sheet. So working in that capacity and then also working on product features. So where I’ve kind of come from more or less building websites that are catering to businesses to sell online now I’ve moved into kind of like more enterprise software. And a lot of the nuances of working within these product spaces and different product features and how to plan accordingly and doing a light amount of user research to the community, things like that. So kind of like an entry level crash course into product design.

Maurice Cherry:

Now. Was it a big shift from E-Business Express? I mean, you’re going from this web hosting environment where you said you were in the back half of your time there doing design to now focusing on product, which I feel like during that time, if we’re talking like, the early 2010s, product was still kind of a new ish sort of term in a way. Did you know what a product designer was when you started there?

Kevin Tufts:

No, because I think around that time also, we were still seeing on job listings, UI/UX. We were seeing like a myriad of job titles that meant the same thing, like visual designer or UI/UX and product designer. So when I moved out to the Bay Area, I had to kind of wrap my head around like, okay, I’m seeing these titles, but the job description is just a product design role interaction designer even. And then the description would be nothing more than just, like, a product design role. So, yeah, it took a while to kind of figure out what the companies were looking for. And then also, what did that mean? Like, what are the job functions that are necessary for me to be successful?

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, there was definitely a shift in the industry right around that time where web designers, graphic designers, visual designers just suddenly started becoming product designer, UX designer. And, I mean, that’s something even I’ve encountered now. Like, if I tell people I’m a designer, I feel like nine times out of ten, they’re going to think that means a UX designer. And I’m like, oh, actually, I haven’t done UX design. Maybe not in the way that they’re thinking it, but I feel like that shift just kind of happened. Was that something that you noticed also?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, I did notice. It naturally sorted itself out because prior to that, I guess in our era, we kind of came up around the time where you’re expected to know all these different things. You had to be a visual designer. Also, Flash was pretty big too, so it’s like you had to know Flash and then programming languages, right? There are all these things. And I was also a front end developer at E-Business Express, so I did a lot of the integration work as well. And when I came to the Bay Area. I still had that mindset that I had to be a jack of [all] trades and know all these things. And then I was noticing that there are actually specialized roles now. Like, no longer are we living in a day and age where they’re expecting you to be a webmaster. Like, I hated that term and seeing that, it’s like you have to know Java. JavaScript, there was all these back end languages that were on our job description roles. When you just want to use Photoshop.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. When I worked at AT&T as a designer, I think my title was just web designer. But we were doing web design, we were doing graphic design, we were doing front end design because we had to, of course, actually build the whole thing from scratch. And this was at the time when layout switched from tables to CSS. So you had to learn that with all the different cross browser compatibility, especially with IE6. And yeah, we had to know like, a little bit of Flash. Actually we used…oh my God, do you remember Swish? Yeah, Swish was like “Flash Lite”, I guess. It wasn’t made by Macromedia, which Adobe ended up buying, but it was a totally different company called Swish, and it was a more, I guess, sort of user-friendly interface to make Flash animation. But we had to know Flash. We had to know a little bit of Java, and I mean, like actual Java, not JavaScript. Ironically, we didn’t have to know JavaScript, but we had to know Java because we would do these web audio applet things and so we had to know how to troubleshoot the applet. So this is one position, graphic design, web design, Flash, Java, and you’re also sometimes doing some debugging of other people’s stuff. It was a lot into one particular title, and I feel like now that’s five different jobs at a company. After your time at DotNetNuke, you worked for a lot of other companies out in the Bay Area. You worked for — I’m listing off here — Workday, eBay, SendGrid, Twilio. And before Facebook, you were at Lyft for a short period of time. When you look back at those positions collectively, like, what stands out to you? Do you remember any particular things?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, I remember at DNN had an amazing time there and I felt like that was the kickstarter to my official tech career in the Bay and just getting my feet wet with engineering teams because we had a team of roughly like 100 engineers or so. And so that was the first time going from like a small web shop where there’s three developers and they’re within arm’s reach, to now I’ve got to talk to engineering leads and have these presentation reviews. So that was kind of like the world that I was living in at DNN.

And then when I moved over to Workday, that was my experience into the world of enterprise software and really how to work within the confines of a design system. Coincidentally enough, I worked on the internal tools team, so that was really unique to be on the team that has to essentially vet and take in requests from other product areas, different components that may need to be built or reviewed to see if there’s any efficacy to having engine spin up resources to bring to life. And then also working across different time zones. So Workday was amazing. And having to work with engineering teams in Ireland, and I’ve also got a couple of trips to Europe out of that as well. So can’t complain with that. The design culture at Workday at the time was growing, so design hadn’t been around at Workday for too long before I got there. I think maybe like a couple of years at the most. So we had a young but super talented design team that was working at Workday at that time, research, I want to call that out as well. So we did have a few research partners that were at Workday. So that was my first time interacting with research, other than me standing up some guerrilla survey or just doing kind of like personal research. My own living from Workday.

So I left Workday and went to eBay. And eBay was awesome because I met some incredible people and I’m still friends with a lot of them to this day. eBay was just a special time in my career where I was able to again, work at a massive company, work on different product spaces. And also, I’m an avid eBay user, so I came in with some personal knowledge of how the product works because some people that work at eBay, they don’t necessarily use the product. I’d say the same thing is probably like for a meta as well, right? Which probably is problematic. But I actually used the thing that I worked on, so that was really cool. Several opportunities to travel throughout Europe, mostly Germany, and eBay was close to home, so I didn’t have that long commute, like a lot of folks in the Bay Area. So that fulfilled my mood, was incredible back then.

And then transitioning from eBay, this is where things get interesting. So I ended up at a company called SendGrid. And SendGrid is kind of like an API communications company, more around the email marketing space. Really powerful tool. A lot of companies use it today. It’s kind of like the rival to Mailchimp for anyone that’s not familiar with SendGrid. So if you know Mailchimp, that’s basically what SendGrid is. And SendGrid was acquired by a company called Twilio. So that’s how I ended up at Twilio — through an acquisition.

When the acquisition took place, SendGrid had a very mature, young, but mature design organization, and Twilio was engineering centric, so they really did not have design. And I think literally there may have been like four designers, four product designers there at the time of the acquisition. Funny story. I’d actually interviewed with Twilio before the acquisition, maybe like a half a year prior to that, and got an offer. Decided that wasn’t quite where I wanted to be in my career because I wanted to go somewhere that had a mature design organization and I didn’t want to go somewhere where it’s just you kind of have to fight for your seat at the table. So I’ve seen some things at that time during the interview process that the folks were incredible, they were great, but I’m like, maybe I’ll pass. So I ended up going to SendGrid and I kid you not, on my first day, my first day in the office with my team and our first team meeting, we got an announcement to basically shut our laptops and we need to receive some news. And the news was that we had been acquired by Twilio. So the company I ran from was the company that ended up acquiring. They got me anyway, so I was the most expensive hire ever.

Maurice Cherry:

Wow.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah. So to wrap things up, Twilio was just an interesting time. PDs were basically working across like anywhere from 4:00-9:00 p.m. At a time. I think I had eight that I was reporting to. So it was pretty chaotic, but at least you were shipping work like, daily. We didn’t have enough design resources. And also it was challenging because I mentioned that Syngra had a mature design culture and organization. So when we came in with a lot of our process oriented things and checkpoints with design briefs, which is necessary, especially in large, fast moving companies, we were trying to get the company to slow down so that we can improve the quality versus just kind of like PM coming up with an idea and ends just building it. And if it doesn’t work, oh well. We wanted to kind of move away from that mantra and more towards being design led. So tiny bit of friction around there, but ultimately they’re getting to where they need to be. And Lyft, I know I’ve done such a tour of duty here in the Bay Area.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, I was going to say.

Kevin Tufts:

Finally — it’s going to stop now. But Lyft, I would say Lyft was a cherry on top for my career. It fulfilled so many things that I had been looking for, where I want to move fast, ship quality work, have a mature design organization, and a mature design system. Right? You don’t ever have to worry about what’s real, what’s not real, what’s in flight. Our design systems team at Lyft, product teams, everyone was just incredible to work with. And so I worked on the community safety team. My short stint at Lyft and the team that I worked on was unique because we got to wedge ourselves in between different product spaces without actually being a full-fledged member of the team. So I got to work on the Driver app and the Rider app. And then there’s some kind of like, unique things around the rental car space, which is Fleet, so there’s a lot of interesting work. And because it wasn’t a massive company, you could move fast. There was a researcher embedded on my team, so it was almost like bi-weekly we were testing things, and I just loved it. So I didn’t have to worry about the design system. Inevitably, when you’re working on the thing, sometimes you’re not working with a system that’s flexible enough to adhere to your needs and what you’re trying to solve. But while working with Lyft, I didn’t have to worry about all that. I just worried about the experience itself and everything else just fell into place.

But the pandemic is what got me to Meta. So when the pandemic hit and no one was going anywhere, no one’s driving, no one’s riding, I’m watching my colleagues, like almost weekly, like different goodbye emails that are going out. And it was a wild place to be in the year that everything seemed to have melted down. So out of self-preservation, and a need for not legit thinking the company was going to go over, I ended up making the jump over to Meta.

So I’ll stop there. And that’s the whole transition to where I am today.

Maurice Cherry:

No, like you said, that is quite a tour of duty. One question I think that really stands out among all of that is, like, how have you seen product design change over the years? I imagine from company to company, it’s probably fairly similar because you’re working on software products. I guess you could say Lyft is software, but it’s transportation as well. But how have you seen product design change over the years since you first started?

Kevin Tufts:

The tooling. I would definitely say, in terms of ease of collaboration, that is one of the biggest things that I’ve seen change. And then the tooling itself. So now that we’ve got these robust prototyping tools, it’s so much easier to demonstrate the design and the experience that you’re working on without having to know some hardcore programming languages. Like, back in the day, it was like you had to know JavaScript or jQuery just to maybe animate a dropdown, right? Or you may have had some ideas around something fancy that you wanted to do, maybe you wanted to have a side drawer appear on a website. But in order to do those things, you had to know a programming language or just mock it up in After Effects, which is also tedious. So I would say just the sheer volume of tools in the collaboration space and prototyping is just incredible.

Maurice Cherry:

There’s another podcast that I produce — I’m not going to mention the name of it — but there’s another show that I produce, and one of the things that we have been exploring through that that I feel like is also relevant to our conversation is like, just how much the browser has become a tool in and of itself. Like, the browser used to just be about presentation. You made a website or something like that, you put it online, whatever. But now, as the browsers have gotten savvier, as different frameworks have been created and such, the browser itself is such a tool to the point where there are services now that only exist in a browser. They don’t exist as standalone software, like an executable file or something like that. Like Figma, you can do full fledged graphic design all within your browser. And like, ten years ago, that would have almost been unheard of.

Kevin Tufts:

It is mind blowing to do that in a browser. Like, through Figma, you’ve got these other tools like Webflow, and trying to think of some other ones that are out there canva I mean, it’s just totally jealous of the new designers, by the way. Every time these tools come out and I have to interact with them, and I’m just like, wow, I really couldn’t use this back in the day when I had maybe 100 buttons that I need to make a change on it. I had to go touch every hundred, you know, component.

Maurice Cherry:

Listen…modern designers will never know the pain of cross-browser compatibility. They will never understand how much of a pain in the ass it was to try to get one design to look the same across different versions of Internet Explorer and Firefox and Opera. Oh, my God.

Kevin Tufts:

Safari. Safari behavioral things. Yeah. [Internet Explorer] 6 through 8 were probably like the nightmares. Six and seven, for sure.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, for a while. I know. There was, like, a whole cottage industry around basically browser emulators. Because if you were on Windows, of course you couldn’t really use Safari. You’d have to use I mean, the Windows version of Safari you could use, but it didn’t even render the same between Windows and Mac. And so you had this software that you’d use that could hopefully reliably look the same between everywhere, and you had these little HTML shivs you had to do to make certain properties work. It was man, it was a jungle out there. It’s only like ten or so years ago. It was wild. Yeah.

Kevin Tufts:

Not that long ago, when I was at E-Business Express, we bought a dedicated iMac for that very reason, so that we could run all the browsers on the Mac to see how they were responding as well. It’s like, I don’t miss those days, but I am so grateful that I got to experience it.

Maurice Cherry:

Right? No, absolutely. Because, I mean, I think there are certain skills, I think, that you build because of that, like being able to really debug and even to sort of refactorize your own code that you’re doing, because you know that if you do it this other way, it’s going to look bad in this browser. So now you sort of learn all these little eccentricities and stuff like that. So now things are pretty standardized between the browser, I feel like, and I haven’t done front-end in a while, but I feel like things are pretty standardized now between the modern browsers like Edge, Safari, Chrome, Firefox are pretty much going to render things pretty much the same.

Kevin Tufts:

Yes. And I think a lot of it’s like the proliferation of frameworks like the CSS frameworks have helped out with the consistency as well. Right. The browsers have the support built in for a lot of the neat CSS tricks that you can do. But then also a lot of people have adopted these frameworks that have that stuff built in as well. So it just really speeds up the design and development process. And I could say, like, for people that are front end developers and they’ve moved over to just being a designer, it’s always been easier to communicate with your engine partners too. So when you need to go into engineering meetings as well, it’s always refreshing to communicate in their language as much as you can. Right. So it helps you out that way as well, career wise.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, you’ve said that there’s no better time to be a designer than now, and I feel like we may have kind of talked about that a little bit now, just with tooling, but expand on that for me. Expand on that thought.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah. So let’s say FigJam, the collaboration tool within Figma. It has really opened up my world where I could send people just a design, like an early design. They can go in there, they can comment, or we can comment, live the collaboration aspect, especially in the remote world. Obviously we’re not all in the same space, but it has been world-changing to get early buy in through Figma, through sharing a link and even doing research. The tooling for research has been a lot better over the years. The last ten years, it’s improved greatly. And so speaking to that, yeah, I’m all about collaboration tools because we have to do a lot of virtual brainstorm sessions or design sprints. And without having that mechanism, I’m not sure where we would have been today. We could have probably been doing design sprint in Google Sheets or something like that, right? Which would be terrible. That has just been world changing for me in terms of just building more momentum and getting buy-in.

But also with prototyping. I’m a big fan of prototyping and I do remember the days of struggling for weeks and weeks through using JavaScript and jQuery to do something relatively simple or maybe I had an idea that’s kind of elaborate but do not have the technical skills to pull it off. So prototyping in Figma, Origami and some of the other tools that are out in the market today. It’s like you spend maybe an hour or two going over some tutorials and then all of a sudden you’re off to the races, making a really immersive, native-feeling prototype that you can view on your phone and even share it. So that’s why I kind of like saying, I’m so jealous of all the folks that are becoming designers now because they’ll never know the pain of taking days or even weeks to do something really simple and sometimes it just ends up being like a throwaway thing.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, I didn’t even touch on mobile. But you’re like, absolutely right about that. I mean, mobile is another thing where a bunch of different environments across different smartphones are going to render things differently. That’s a whole other part I didn’t even consider. I’d say also just education back in the day a lot. I mean, this stuff was really online. We were all just sort of reverse engineering and looking at View Source code and trying to figure stuff out. And there were books that came along eventually because some people might have been a little bit ahead of the curve, but you couldn’t really go to school for this. And now you have like, Treehouse and you’ve got General Assembly and there’s no short share skillshare. There’s YouTube videos. There’s so much stuff now around education that just did not exist when we were trying to learn design back then. Especially if you were self taught. Like, if you were self taught, you really were self taught because there were not even just these educational platforms to help you to figure this stuff out. You really were doing a lot of trial and error.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah, great point. I don’t know how I could even forget that because that was a huge part of my life and career and I felt like I took a long road to get to where I am because of that fact. Back in those days, there were very few tutorials online. You could find some Illustrator tutorials. Shockwave. I’m trying to think of some other Macromedia products. That ColdFusion. Fireworks. Yeah, you could find some really remedial tutorials out there, but that was about it. And so those early days, I had to go to a bookstore and look at design magazines. I think Computer Arts was a godsend coming from publishing [in] the UK. But yeah, that was it. It’s like you go to a bookstore and you get all these design books and then I would get some programming books just to see what’s going on. But like you said, maybe you found a website that was cool and you got to go view Source and like, okay, what’s going on here? And then you try to break it down.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah.

Kevin Tufts:

So, yeah, all this stuff that we have, like, access to education and just these online schools and I love it. I’m here for it.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, I remember back in the day I used what was it called? Dynamic Drive. Do you remember Dynamic Drive?

Kevin Tufts:

No.

Maurice Cherry:

So Dynamic Drive was the site that basically just had code snippets. Like, they didn’t really give tutorials. They kind of told you how to implement it, but say you wanted to make it so someone couldn’t right click on your website. Right? Yeah. You could go to Dynamic Drive and find the code. Snippet copy it, copy it, paste it between the head tags, and then all these different no one could right click. Yeah, they really tell you how it worked. You just were like, oh, this can do this. There was a lot of trust, I’ll put it that way, that you weren’t putting something malicious in your site. You would just, oh, copy, paste that and…oh, God, what’s the other one I used to use a lot that was sort of more educational based that’s still around now called…W3Schools. Yeah, that’s right. W3Schools. And I remember because I was also teaching design at the time, this was like, what was this, 2011, 2012, maybe? And I remember telling my students, like, don’t use W3Schools. They call themselves W3Schools because it was www. But I think folks also confused it with the W3C, which is the Worldwide Web Consortium. And I was a member of their Web Education group. And they would tell us, do not tell people to use W3Schools. It is not sanctioned by us. It is not our thing. But it was also still teaching people. It was teaching me how to use some of this stuff. But I would have to tell my students, don’t use W3Schools. Think of it as a reference, but don’t just copy and paste stuff from W3Schools and then turn it in as homework, because I’m going to know that you did that, because I do that, so don’t do that.

Kevin Tufts:

Oh, my goodness, man. Yes. Absolutely. We said dynamic drive. I wasn’t even like it didn’t even ring a bell. But I remember using them to get a script, to do the animated cursor. It had all the types of weird, just weird things. It was almost like the dollar store for scripts.

Maurice Cherry:

Not the dollar store! That’s a very accurate piece of comparison there. Back when HTML…I think it was called DHTML back then. Yeah. Oh, man, what a time. What a time.

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

What advice would you give to someone out there who’s they’re hearing your story, they want to follow in your footsteps. What advice would you give them?

Kevin Tufts:

You know, as you’re trying to figure out what aspect of design you may want to focus in? Experiment, try it all. And as we were just talking about, there’s so many resources online where you don’t even have to pay a penny to try something out, right. But really just be curious on how things are done, whether it’s processes related to product design or maybe how to run a design sprint. There’s so much, and you’ll kind of eventually find your way. Some people generally know, like, hey, I’m not a great visual designer, but they want to get more into the UX of things. Right. And that’s great too. So it’s all about kind of like, figuring out your career path and what your passions are, what your strong suits are.

For me, I love product design, but I’m also really heavily into micro-animation, so I lean towards these prototyping tools. But yeah, it’s like, sky’s the limit. It’s kind of like the advice that I would give them informal training. Like, if you are able to get into a good school that has a great product design program, that is awesome. I know Carnegie Mellon has one. Tufts University has, like, an HCI class. I think most big universities these days probably have some facet of, like, a product design class, but then don’t also have to go to a giant university for this type of an education. Like we already mentioned, it’s all right there online. Just use the resources that are available to you.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, I noticed that the URL to your website is pathstraightforward.com. What does “path straight forward” mean to you, like, in terms of your life and your career?

Kevin Tufts:

Yeah. So I was trying to have a domain name that sounded relatively cool. And at first, I’m like, this is not going to have any type of esoteric meaning or anything, but really, it just summarizes the journey that I took in order to get to where I am today. Because it was really long. It was hard, but I knew that I had a plan, and I just kind of stayed focused on the journey and the path moving forward, and that’s kind of what’s got me here. And I still have a long way to go.

Maurice Cherry:

Where do you see yourself in the next five years? I mean, you’ve mentioned this kind of tour of duty that you’ve had around the bay at these different companies and such. What does the future look like for you?

Kevin Tufts:

So there’s a couple of things. I think I want to start to move more towards design systems because I really do enjoy working with my design systems partners. And so over the years, I’ve had a number of contributions to different systems that are available. But between that and mentorship becoming, like, having a stronger influence in mentoring younger designers, I mentioned that I was involved in a program here in Oakland, but it’s really impactful when people can have someone that they can talk to and get directional advice for their career. So I want to have more of a stronger influence in mentorship circles.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, just to kind of wrap things up here, where can our audience where can they find out more information about you, your work and everything? Where can they find that online?

Kevin Tufts:

Yes, you can reach out to me on LinkedIn. So it’s LinkedIn.com, and it’s my first and last name, Kevin Tufts. So feel free to connect with me. I am always willing to have a coffee chat with anyone that’s curious about my background or just really general questions about design and my website since I’ve been employed for so long. I’ve kind of taken down a lot of the work there, but also there are some social links in there. You can reach out to me on my website and contact me directly.

Maurice Cherry:

All right, sounds good. Kevin Tufts, I want to thank you so much for coming on the show. I mentioned this prior to us recording. We have a mutual colleague, Kim Hutchinson. Now she was Kim Williams when I first interviewed her, but Kim sang about your praises. She was like, “you got to get Kevin on the show. He’s such a cool guy. He’s such a good guy.” And I can tell just from this conversation, like, she’s 100% right. You’re down to earth. You know your stuff. And anybody that I talk to that has been around since the early days of the web that has built stuff from scratch is, like, automatically cool with me because, you know, the trenches that we’ve had to go through to still be…I would even say relevant. I want to say that. But to go through the trenches, to still be working and doing what we do now after 20 years is amazing. And I think you certainly built a fantastic career for yourself, and I’m really looking forward to seeing what you do along with the mentoring track and everything.

Maurice Cherry:

So thank you for coming on the show.

Maurice Cherry:

I appreciate it.

Kevin Tufts:

Maurice, thank you. And I really appreciate you having me on the show. And it is awesome that you’ve got a platform that you can expose different types of people from various backgrounds. So, yeah, man, kudos. I appreciate it.

Sponsored by Brevity & Wit

Brevity & Wit is a strategy and design firm committed to designing a more inclusive and equitable world. They are always looking to expand their roster of freelance design consultants in the U.S., particularly brand strategists, copywriters, graphic designers and Web developers.

If you know how to deliver excellent creative work reliably, and enjoy the autonomy of a virtual-based, freelance life (with no non-competes), check them out at brevityandwit.com.