Maurice Cherry: All right. So tell us who you are and what you do?

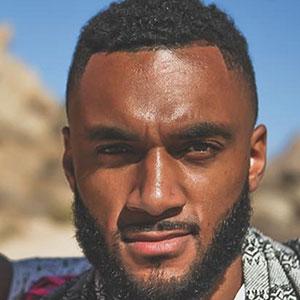

Handel Eugene: Yeah, my name is Handel Eugene. I’m a Haitian-American, [inaudible 00:00:06] disciplinary artist, animate and designer. I’m also an instructor. I dabble in public speaking from time to time and I’m currently residing in the San Francisco, Bay Area.

Maurice Cherry: Nice. And now, you told me, right before we started recording that you were permalancing and you’re working at a bunch of different companies out there. Can you talk just a little bit about the types of things that you’re working on?

Handel Eugene: Yeah. So right now I’m freelancing for some different companies out here, basically in Silicon Valley. Right now I’m currently at Apple, and right now I’m just… Obviously Apple being Apple, super secretive, can’t talk about a whole heck of a lot what I’m currently working on. But I can touch on a little bit of what I’ve done in the past for them. I’m currently working on whenever they have a new product release or they have their events and such, to unveil their new products or their new service and what have you.

Handel Eugene: You’ve got to promote those different aspects. And my job is just to kind of like do creative advertisement, creative promotion, creative material and content to help unveil and roll out some of those different products. I’ve also worked on in-store content as well, the [inaudible 00:01:23] device content as well for them. Not just on Apple, but also I’ve gotten the opportunity… Fortunate to have the opportunity to work at Facebook and Google, doing those same different aspects. Just kind of creative advertisement and also doing some work on the platform internally as well.

Maurice Cherry: Nice. So what is a typical day like for you? I know you’re kind of bouncing between these different companies, although you’re mostly at Apple right now, but what’s a regular day like?

Handel Eugene: Yeah, yeah, of course. So yeah, I work in the motion graphics industry. It’s kind of like more of a specific area that I primarily work in and it’s called motion graphics, but I guess it falls under the umbrella of creative advertisement. So yeah, like a traditional day, let’s just say in my free day… I’ve worked in LA for seven years. So back then a job would come in through the studio. We’d have a brief, and a client’s looking to promote a service or a product or show, a new show.

Handel Eugene: Or even having the opportunity to have worked on a film. Obviously, that aspect as well. And our job is to service the client’s needs and provide them with creative solutions, creative designs, creative advertisements to kind of help tell their story and meet their needs of whatever they’re looking for in particular, and visually. What I like to describe myself, it’s kind of like a visual storyteller. Basically taking these aspects and these elements that are on paper, these kind of rough ideas and presenting different design options for them.

Handel Eugene: It can be design and animation. Either or, or both combined, and delivering that to the client. So I guess a traditional day just to get into the kind of nuts and bolts is yeah, you come in, you’ve got your brief, you’ve already been briefed on the project and yeah, you just chipping away at designs. Sometimes you have pitches where those are kind of like short form like, “Hey, let’s just kind of provide a buffet of options to the client for them to pick and choose from.” And once the client picks a direction, then we’re kind of like full steam ahead and just into production.

Handel Eugene: Taking that concept that won us the job and executing it. Executing it into design phase and animation phase, and ultimately delivering the product for the client. So it’s just kind of working on those different aspects. Again, I guess typical days, I’m getting more specific, I’m designing a Photoshop, animating side after-effects or cinema 4D. And I guess, those are primarily where I’m spending a lot of my time. Also putting pitch desks together, writing briefs and content and material. So yeah.

Maurice Cherry: Okay. Now what’s kind of been the biggest challenge that you faced with doing a lot of this? Like you’re working for these large companies, you’re looking at briefs and pitches and stuff. What’s the biggest challenge you face with doing all this?

Handel Eugene: Yeah, the biggest challenge, I mean, there’s lots of different ones. I guess trying to figure out what the biggest one would be. Trying to stay fresh and creative. It’s interesting. We’re all fortunate as designers and artist to do something creative for a living, which is amazing. But sometimes that can be exhausting especially if you’re kind of at a rapid pace. Some studios kind of work faster than others and kind of like have a lot of material and content that you kind of just jump on and get pulled on left and right.

Handel Eugene: So sometimes, it can be a little taxing. So I think one of the biggest challenges is to stay inspired, stay fresh and stay creative. Not to get burnt out. I think burnout is a real, real issue in our industry just because of the nature of what we do. Can be labor intensive, for sure. I mean if you’re working long hours, sometimes you can kind of get tunnel vision and it’s kind of hard to see the big picture. So I think that’s one of the more challenging aspect, is like trying to find that balance of working hard on something because you want it to be great, but then trying to not burn yourself out, stay inspired and especially be inspired outside of work.

Handel Eugene: So that way, the experiences that you’re having outside of work can kind of fuel and feed and form kind of your ideas internally at work. Because again, yeah, like working in a creative field, you’re always being asked to create new, fresh creative content all the time. So sometimes that can be a little hard at sometimes.

Maurice Cherry: Emotionally, I mean it’s something that you see anywhere from animation to product reviews to a number of different things. So I can imagine after a while it’s something… I’m just thinking to myself like as a viewer, it’s something you kind of take for granted. Like you expect everything to be able to move and work well. But certainly I think modern digital design, I should say, features a lot more animation. I would imagine one of the challenge, and you can correct me if I’m wrong here, but I’d also imagine one of the challenges is making sure that you stay kind of unique in a way?

Handel Eugene: Right. Yeah, absolutely. So what? Like let’s say 10, 15 years ago, our industry to have as a kind of like for clients was a luxury. It’s like if you knew how to key frame something from point a to point b, I mean you had a job and you were in demand. But nowadays there’s just so much content, and the bare bench entry has definitely been lowered. Technologies and applications have become cheaper, things have become more accessible. So there’s been definitely is a flood of material. Obviously, the way we consume content has changed.

Handel Eugene: Obviously with content coming straight to our phone with Facebook and Instagram. So yeah, there’s a lot more, I don’t want to call it noise, but there’s a lot more content out there for us to consume and a lot of more content that’s fighting for our attention. So yeah, to stand out is definitely, absolutely a big challenge. Stand out from the crowd because yeah, you’re competing against all these other… Some can be distracting and some can be really good content. Yeah, you’re competing against lots of other really good content as well.

Handel Eugene: So yeah, that’s always, always a challenge. You want to create something that’s meaningful, that’s impactful, that’s engaging with the audience and that’s something that we’re always considering and trying to meet and provide for the client. And yeah, that can be super challenging as well because that’s something you got to stay on top of and understand. And there’s trends, there’s aspects that you want to try and fight against, but then also there’s aspects that you need to incorporate because it’s new and it’s something that we’re… Yeah, it’s always something that you’re always balancing.

Handel Eugene: And like you said too, you touched on a little bit like it’s one of those things that requires a whole heck of a lot of work, but people nowadays may take for granted and just kind of like… Because we just consume so much content nowadays. So it’s definitely challenging for sure.

Maurice Cherry: One thing I’m curious about, and you can let me know how much of this you can speak on or not, is accessibility. So of course we have, like you said, there’s all this content. Things are always moving and shifting and changing. Even with just I think regular web design now, there’s a lot of animation that you can do with coding. Like with CSS, you can make things fade in and fade out or transition or stuff like that. How does accessibility play into your work, if it plays into your work at all?

Handel Eugene: Now, when you say accessibility, are you saying kind of like how readily available some of these animation techniques are to the general audience and general consumers? Is that what you’re-

Maurice Cherry: I’m thinking more I guess from the viewer end, like say for viewers that have say visual impairments or if a lot of moving things cause motion sickness or something like that or even, you know colorblind. Things like that.

Handel Eugene: Right. Absolutely. Absolutely. I’ll tell you, that’s something that there’s a team dedicated to that. There’s always like this struggle between creatives and let’s say the legal department or so. The creative wants to push this idea forward and be like, “Okay, we’ve got to consider this audience, we’ve got to consider this aspect or this might be too much for this particular audience.” So I’ll tell you, just as a creative and an artist, we’re always putting the creative first and pushing the creative. And then we kind of allow those two different departments that specialize in those areas to kind of rein us in and inform us of different aspects that need to be more accessible or more readable or adjustments and alterations that may need to be made.

Handel Eugene: So there are definitely departments that are dedicated to that, that will inform us. And we’ve definitely got through revisions and made adjustments that have made our content more accessible. I think just in general as a creative, and this is kind of like one of the fun part of the process, especially the pre-production process is you just start broad. You start broad, just kind of like trying to find, come across something. Those happy accidents are really something that you’re always searching for. And kind of like once you start broad then as you progress through the production pipe, I mean you start to kind of chisel away and get a little bit more narrow, a little bit more focused.

Handel Eugene: Trying to figure out what you can take away or what you can adjust to kind of make the content as strong as possible, but also reach as much people as possible. So that’s my angle and my perspective on it a motion graphic standpoint. But there’s been a lot. I’m sure lots of people have different experiences with that, but that’s just my particular experience.

Maurice Cherry: Now, I’m curious about that just because I know that there are… I mean we’ve had people on the show that have accessibility experts that have talk about this sort of thing. I was actually also even thinking of most recently Domino’s Pizza had filed a case and it even went up to the Supreme Court around accessibility. And I think it was more so just about accessing the site. But then also a lot of modern sites put motion in their transactions and interactions in a lot of ways that sometimes are good, sometimes they get in the way. Like parallax scrolling and scroll jacking and all that sort of stuff where you’re like, “I just want to view the page. I don’t need you to guide my decision.” And that sort of thing.

Maurice Cherry: So I was just curious about how you deal with that or if you deal with that at all. But it’s interesting that it’s kind of is a thing with legal that you have to sort of go back and forth with. I didn’t even consider that.

Handel Eugene: Right. Yeah because it’s definitely not our area of expertise. I guess for me as the content that we’re creating, for example, working at a studio in LA. Whenever we get a brief there actually has been a lot of thought and already a lot of development that has went into the particular idea. And it’s just kind of like on us to develop and execute it. And once we deliver it to the client or present our first rough draft or first… Like there is a chain of command as far as where it needs to go and different eyes have to get on it to kind of approve it and get sign off on it, including the legal team as well.

Handel Eugene: Like this is something that I’m sure artists can relate, who’ve gone through this. But it’s always sucks whenever you get close to the finish line and then that’s when legal gets their eyes on it and then they ask for changes that should have been brought up ages ago, early on in the process. Again, from just my perspective, I wonder if pure graphic design, like that’s something that is considered more from the get-go than in my industry, as far as motion graphics and motion design. Yeah, just honestly, it’s not something that is at the forefront at the beginning of production, but it’s something that does come up in production and we kind of make adjustments and pivot if it’s something that’s not readable or accessible and such.

Handel Eugene: And again, most of my content that I create is in video format and stills and such. I don’t dwell too much into the web design space, because I just designed my own website. But yeah, most of the stuff that you’ll see that I’ve done is kind of like on the TV screens or content that you may consume on your phone or it’s like having… Fortunate to have to work on a couple films as well, so.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. So it’s like more media and less web, I guess.

Handel Eugene: Right, right, right.

Maurice Cherry: Okay.

Handel Eugene: Yeah, definitely.

Maurice Cherry: So you mentioned being in LA for a number of years. You started out your professional career at Royale, which is the creative agency there. What was your time like at Royale? How did it help prep you for the work you’re doing now?

Handel Eugene: Yeah. So my time there was great. I absolutely, absolutely loved it there. And it was my first job out of school so I interned there for three months. And it was funny because I was just finished up with school. I was in Florida and I’m trying to convince my parents to be like, “Hey, can I move to LA?” And they were like, “Oh, you got a job up there?” And I was like, “Kind of a job. It’s an internship. Nothing’s guaranteed but it’s pretty promising. If I landed, it’d be a dream job for me.” And so thankfully, they were hesitantly supportive of me, encouraging me, supporting me to go out there.

Handel Eugene: And yeah, when I got there I just worked my butt off for those three months because this truly was a dream. Is a place I wanted to work since the beginning of school. And thankfully I was able to prove myself to them. I used my time there kind of like… I like to say this a lot to other people, I used my time there kind of like as grad school where I was still young, fresh and hungry but I still wanted to continue learning. I was like using it as like it’s a continuing education program to where I was trying to get my hands dirty as possible, testing out.

Handel Eugene: And I was also trying to find like my voice and what I really wanted to do because there was so many opportunities to touch different things there. And I was fortunate, grateful. Not all internships are like this, but thankfully at Royale, they do a good job of grooming their interns there by giving them lots of different assignments besides just the drought work or… Actually I did have to walk a dog once. But majority of the work day I got to do was like working on some real portfolio quality content that was great.

Handel Eugene: And yeah, so I was like a sponge, just trying to soak up as much information as possible and as much as possible. Mainly because I didn’t know how long they were going to keep me and I didn’t know if I had to go find a job after this. So I was like, “I’m going to try and take full advantage.” Because the saying, take advantage what others take for granted. I was like, I’m going to just work my butt off and grind as much as possible here so that way, I’m going to put my best foot forward and if I get [inaudible 00:18:40], great. If not, at least I can take all this experience with me to the next opportunity.

Handel Eugene: Thankfully, they kept me around and eventually went staff there and I worked there for five years.

Maurice Cherry: Wow.

Handel Eugene: Yeah. And seriously, up until the point that I ended up leaving, I want to say it still was like grad school and continued education. Like I was always learning, always pushing and always trying to grow and get better and push my skills there. And thankfully it was the perfect environment to allow me to do that. I really feel like if I’ve achieved any type of success, it’s primarily due to the foundation that I had during my time at Royale.

Maurice Cherry: What were some of the projects that you worked on there?

Handel Eugene: Man, I remember when I was, not to jump too far ahead, but when I left, I went back and tracked all of the projects that I worked on during the five years I was there. And I’m blanking on the exact number, but I knew I averaged about two projects a month there, and some of the projects I got to work on were just for clients all across the spectrum. I mean, we worked for Apple we works for Google, we worked for Toyota, Starbucks, Nike, Adidas and all those big brands. And of course like lots of local brands as well, like In the Raw and all kinds of different… Like video games, EA and the like.

Handel Eugene: And just working on creative content for them to kind of help promote, like if it’s a new shoe or new apparel or it’s this new promotional program at Starbucks that they’re rolling out for October, whatever the case may be. So all kinds of different content and it was great because again, having the opportunity to work on all those different projects just kind of got me up to speed so quickly with the industry and helped me learn. And thankfully I had an amazing group of artists and mentors and people who supported me and saw how hungry I was and kind of leaned into that and fed into that and gave me opportunities to continue to challenge and prove myself while I was there.

Maurice Cherry: Now, as I was doing my research, the biggest thing that I saw that came up was that you had even done some work for Marvel, more specifically for Spiderman Homecoming. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Handel Eugene: Yeah, yeah, of course. I got the opportunity to work for a Marvel two times, actually, in two different occasions. And the first one being for Spiderman Homecoming in the summer… No, late spring of 2017. I got the opportunity to fly out to New York and work at a local studio there called Perception, which was working on the titles for Spiderman Homecoming, and it was always my dream. It’s always my dream, right? To work on a film. Even before knowing that I would ever be in this industry, I was like, “It’d be cool to work on a film one day.”

Handel Eugene: It was cool when Perception reached out saying they’re interested in bringing me on board. It was for film, but they couldn’t tell me what film it was for and I was like, “I don’t care. Whatever film it is, I’m your guy. Let me know. I’ll take the gig.” And you have to sign the NDA paperwork and such, and finding out what the film was it was like, “Oh, wow. This is awesome.” Because it’s actually a film that I truly want to see. And it’s cool to be able to help out and work on it. And it was cool because I remember going into the studio and looking at all the storyboards that were onscreen and I remember it’s like, “Oh, Donald Glover’s in this movie.”

Handel Eugene: I was like, “Oh, that’s so dope.” Yeah. It’s like just seeing the cast and everything like that and the title itself. The work that I did on the film was the end-title sequence. So it’s actually the last thing you see before the credits roll. It’s a glorified version of credits where you see, directed by… And you see, starring… And you see the main actors and directors and the high profile figures that worked on the film, that were behind the film and were starring in the film. You’ll see them in end-title sequence as pretty much just taking the best of the film and interpreting it in a creative medium.

Handel Eugene: In this particular case for Spiderman Homecoming, our task was to take basically content from the film and make a title sequence that fell under the theme of high school art class.

Maurice Cherry: Okay.

Handel Eugene: Yeah, that was super fun because it was just like going back to your childhood and just like finding these different mediums of clay and plasticine, and colored pencils and watercolors, and all these different fun mediums to just kind of get your hands dirty and just go and just kind of create traditional art, which is great. And then bring that in, scan that in, stop motions, and bring it in and just incorporate it with digital assets and just animating all that together to create this really, really fine title sequence that you see at the end. So that was a whole heck of a lot of fun. And that was the beginning of what allowed me to have the relationship with Perception.

Handel Eugene: So I must’ve done a good job for them because they asked me to come back and work on another high profile film for them, which was Black Panther.

Maurice Cherry: Oh.

Handel Eugene: Yeah. And I have to say, when I was working there, I was working on the film. They had already started doing some early development on Black Panther. They were doing some research development, especially in their UI animations and their future tech designs. And while I was working there, I kind of saw that they were working on this. They’ve been working on it for like a year now. And I was like, “Guys, look this Spiderman Homecoming job, this is cool. This is cool. But man, would I love to come back and work on this, on whatever you guys are working on for Black Panther. I’d come back in a heartbeat.”

Handel Eugene: Because I was living in LA, but I flew out to New York to live temporarily there, just to work on that film. And I was like, “I’ll do it again in a heartbeat.” And thankfully they did. They called me again and it was like, “Hey, we’ve got another assignment coming in and we’d love to have you work on it.” So yeah, that led to the next opportunity to work on my second film, which wasn’t a bad film to work on, which was Black Panther.

Maurice Cherry: Nice. We did a whole episode on the art and design of Black Panther. I mean, you love Black Panther clearly. [Crosstalk 00:25:56] but no, I didn’t know you worked on that movie too. That’s dope.

Handel Eugene: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, that was-

Handel Eugene: Yeah, that was probably the highlight of my career. I ask myself this all the time. I’m not sure what’s going to top that. I don’t know. But it was really a dream project to work on that. And you know, it’s funny because once she reached out to have me come speak, I’d been listening to some past guests on the show, and Hannah Beachler, I was listening to her episode and it was cool to work on my aspect, but I was like, wow. Like it’s how hearing her perspective on the film, which was great.

Handel Eugene: Like, I got to work on the film but I didn’t get to hang out with Ryan Coogler, and it’s actually just seeing how close she was to the production of that film was like, so awe inspiring. So, I just got to be kind of like a small fish, and I got to work on the first and last thing you see on the film, the prologue sequence, and the end title sequence which was a lot of fun, but it was just so, it was just so, because I was like, it was like reliving it all over again. You know, just hearing her perspective and hearing what she had done on the film. But, yeah.

Maurice Cherry: Now, one thing I have to really give to Marvel is that they have really started, and I guess I still do in a way, they’ve trained audiences to sit through the credits.

Handel Eugene: Yeah.

Maurice Cherry: So you can actually, and I don’t know how many people are really paying attention. I would imagine they are because they want to see the mid credits scene, after credits scene. But, you now get to see just how many people have contributed to the work that you just saw. You know, before you watch a movie and it’s like as soon as those first few credits, people are up and out the door. Marvel movies, people will sit through the whole thing and I’m assuming they’re looking at all the names and being like, wow, there are like, thousands of people that went into this. And it wasn’t just the actors on screen. Like, it was like an almost a city of people that have helped to make all of this happen. I really have to give that to Marvel, in a very subversive way, making moviegoers appreciate, or at least have some sort of a recognition that a lot of people go into the work.

Handel Eugene: And you know what? You know what you want? A new found appreciation you’ll have for the amount of people that work on the film is everybody who came up to me, because my name was in the credits, which was super, super awesome. I was bummed because my name wasn’t in the credits for the Spiderman homecoming. I wasn’t sure if was going to be on Black Panther. Like, that’s one thing I would love to have, because I could show my grandkids this and thankfully it was. Everybody that came out to me, I was like, “Yeah, I sat in the theater and I had to look for your name for so long that had to go through all [crosstalk 00:29:02] , and it was so long. And then, by the time we saw your name, it was too late. It was like, we screamed like two seconds of your name, scrolled past”, and it was like, you have a new found appreciation whenever you’re trying to look for a specific name in the credits. Then, that’s when it’s like, wow, you really have a new perspective on how many people really worked on that.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah, I mean the fact that it’s in there is what’s important. Whether you got to see it even just for a few seconds, it’s there. It’s there for posterity. So, you don’t have to worry about that. So, you mentioned Florida, that’s what you grew up, in Florida?

Handel Eugene: Yeah. Yeah. Grew up in Florida. Born and raised.

Maurice Cherry: Was art and design and all of this kind of like a big part of your childhood growing up?

Handel Eugene: No, not at all. And it wasn’t discouraged or anything like that. It was more of, it just wasn’t introduced. Yeah, we dabbled in art, but it’s an elective, right. And you take that art… I had some drawing skills and everything like that, but nobody ever encourages you to like, “Hey, you’ve got something there. Maybe you should try to look into the [inaudible 00:30:13] .” Nobody even knew that you can make a career out of, at least not in my circle of influence. And it’s funny, because my brother, I always saw him as the creative in the family. He would craze on comic books, and he would sketch all the time, and draw. But it was just always like a hobby thing.

Handel Eugene: It was just like a fun thing to do. I kind of got started with all of this… kind of by accident, because I took TV production for three years in high school, and the only reason I took TV production was because my brother recommended it, because he said it’s an easy A, and there’s a couch in the room so you can hang out. So, it was like super chill and [inaudible 00:31:05], he’s got to do the morning show. And, for two years of the three years I took TV production, I was just chillaxing. I was just hanging out, just like, enjoying the time, easy assignments. And, it was fun. It was cool, but it wasn’t anything that we were pressured to stress about or anything like that.

Handel Eugene: But, for some reason, I ask myself this all the time, for some reason, for the life of me, I don’t know why. But, at the end of my junior year, I had this quarter life crisis, can’t even call it quarter life at that point, where I was like, “Man, I’m going to college in a year, and I have no idea what I want to be. So I got to figure out.” I thought when you go to college, as soon as you’re a freshman you have to know what you want to do, and you have to decide, and spend four years learning that. I thought that’s what college was, little did I know.

Handel Eugene: And so, that summer I was like, “All right, I’ve been taking this TV production thing. Let me try to take this thing seriously. I do know a thing or two about cameras, and editing, and I have done a couple of assignments. So, let me try to take it serious this year.” And, one of the best things anybody’s ever done in my career is my TV production teacher, Joe Humphrey, which he, this was like probably the simplest gesture, but it meant the world to me, is he saw how hungry and ambitious I was becoming to learn more about TV production, that my senior year he gave me the title Executive Producer of Terrier TV. And, to this day, still the greatest title I’ve ever been granted, and probably ever will be granted because he bestowed upon me this prestigious honor that I didn’t think that I was worthy of, and I was executive producer. It was the first time I’ve ever had a title of anything.

Handel Eugene: I felt like, it’s very empowering. So I was like, “I got to live up to this title that I now have.” And, so I took it even more serious and I was kind of like leading the department and doing video editing, and all that. Long story short, I did football highlights that that kind of got me some recognition, and eventually landed me a scholarship to go to University of Central Florida, where I learned and developed, and found after effects there and found that there’s this whole new industry, this whole new department. I didn’t know what the industry was. I thought I just wanted to major in after effects. I didn’t know about motion graphics or motion design at the time, but I started learning more and more and decided that I was at University of Central Florida, which was great.

Handel Eugene: I was at UCS sports video. I was kind of like a PA there and learning, and learning, and I was a camera man for their football team and I would record their practices, but the only reason why I was doing that it was because they also have this production department, which isn’t a job, they don’t have a job for you, but you can kind of like volunteer your hours. So my primary responsibility was to be this camera man and record practices, and work your way up to recording games and stuff like that, which I wasn’t too interested in. I love sports, but I just wasn’t crazy about that. But, I was volunteering my time, especially at nights going into the control room with their production room, like learning, editing and that kind of stuff, like picking up avid at the time.

Handel Eugene: And also, that’s where I met my first motion graphic designer. There was one in the department, and I saw what he was doing. So I picked up after effects to try to make my video highlights better. And then I just opened up this whole new world of possibilities. I was like, “Oh wow, there’s people that are actually doing this. Oh, you can actually major in this and go to school for this.” And so I looked into it more and more and more, and eventually transferred from University of Central Florida to Full Sail. So, I think your question was what started off with Florida. I kind of went on this long little journey leading up to like me getting into Full Sail. But yeah, I grew up in Florida. That’s kind of how I got into the arts.

Maurice Cherry: Full Sail has a great reputation in the motion graphics and digital design industry, I think probably more so than some. I think, probably a lot of four year, I mean, Full Sail is a four year institution, but you know what I mean, like some traditional liberal arts college kinds of places. And actually, when you were at Full Sail, that’s when I first heard about you, I’ve mentioned that I saw, I was a feature in Graphic Design USA. It was you and another student, I think another Full Sail student, maybe at a different location that were being profiled. I think Gordon K., who’s the publisher had asked a few questions about what are you working on, and that sort of stuff. And Full Sail caught my eye, one, because of its reputation, but two, because for-profit universities kind of get a bad rap in general, I think with education.

Maurice Cherry: Certainly, we’ve seen in the past three or four years, places like Westwood College and others like that, where they’ve done all this marketing for students, but they’re not accredited, and then they get shut down, and then it makes you wonder, “Well what’s the value of the degree?” or anything like that. But, for-profit education has tended to really make an impact in the design industry. General assembly is technically, I’m using air quotes here, but it is a for-profit model, where people sign up for classes and it ends up becoming a bit of a feeder industry into other positions, and things like that. And it sounds like Full Sail really kind of helped after you went to UCF. Full Sail is kind of what really prepped you for the work that you did at Royale. Is that right?

Handel Eugene: Yeah. So, it’s interesting that you said that, because there’s mixed reviews, right? It’s all just depending on your experience there. And I’ve had people who wouldn’t recommend Full Sail to anybody. And then there’s people like me who had a great experience there. And I think it’s largely due to the individual. You know, like actually, truthfully, honestly, I would have a hard time recommending Full Sail to anybody, not because of the institution, because more so it’s about the individual. Art school just in general is expensive, and I highly encourage anybody who’s looking into it to make sure that you’re at the right point in your life, to really be committed to something that’s going to really affect you for the rest of your life.

Handel Eugene: Because, I think one of the most tragic things is like having a friend who was a classmate of mine who’s not in the industry. He’s not even doing anything remotely close to, motion graphics, emotion design and such, because you don’t want to go to school to figure out what you art school to figure out what you want to do. That’s a formula for disaster. You want to make sure that, I think also too, a big thing is maturity. You want to make sure that if you decided to go to Full Sail, or any art institution, that you’re prepared to be fully committed to it and the more experience you have coming in, the better. That was probably my competitive advantage, but I was there, and why I was able to maximize my time at Full Sail is because I came in and I already knew the tools.

Handel Eugene: There’s one advice I would give to anybody, which is don’t go to art school to learn the tools. You can learn that anywhere. You can learn that online. There’s so many resources online to help you learn the tools. So, because I knew the tools, I was already ahead, and I was able to just focus on just creating projects and portfolio quality work. As soon as I got into the door, I didn’t need the beginning classes that they had you take, I was just spending the whole time just working in designing and animating. I didn’t have to go through the hurdles of doing the tutorials as any other.

Handel Eugene: So, a large part of it. Yeah, for sure, the institution provided me so many resources and was actually gave me access to Jayson Whitmore and Brian Homan who are the owners at Royale. Jayson Whitmore is an alum of Full Sail and he comes back to speak every so often to students at Full Sail. And Full Sail gave me access to him. I was fortunate to be able to show my work to him in a closed room with a couple of other students that were doing good work, and we got to present our work to him, and he eventually recruited me out there to come, and gave me an internship opportunity, which really just kind of jump-started my whole career.

Handel Eugene: So, from my personal experience it was great-and I went through the accelerator program. Now, they have the four year institution program. But I went through the accelerated program where it was 21 months, just under two years, and you go to class five days a week, eight hours a day. And it was intense. It was almost like a bootcamp almost. And again, that’s why I say as I can’t recommend that to everybody, because everybody isn’t used to operating under those conditions and everybody isn’t mature enough to fully take advantage of that particular aspect of it. But it was great for me, because it just got me up to speed. I had already done two years at University of Central Florida, so I already had like an unofficial Associates , as far as just having an experience in my industry and having gone through those early freshman, sophomore hurdles, or what have you. So, as soon as I got to art school, which is where I really wanted to go, I just hit the ground running.

Maurice Cherry: Now you’ve done work for Marvel, you’re doing work for Apple and Facebook and Google. So it’s all really paid off.

Handel Eugene: Yeah. Yeah, it really has. You know, it’s funny because I didn’t have anyone growing up that encouraged me to get again to the arts. But when I did transfer from an accredited university like UCF, University of Central Florida to this, what some may consider as trade school, to pursue the arts. There was definitely some pushback. There was definitely some people who discouraged me from doing that. And there were a lot of people- it’s interesting to hear you say that you’ve heard some positive reviews, but there’s definitely a lot of people, a lot of naysayers who told me the opposite, who gave me a lot of negative feedback. Like, “Oh, I had a cousin that went there and he just wasted a whole lot of money.” It’s like, “Don’t go there”, this, that and the other.

Handel Eugene: And that’s why I say it’s truly dependent on the individual. So , I went in there a bit hesitant because I was- not hesitant, but fearful of failure. I’d heard stories of people coming here and having failed, and I kind of used it as fuel to my fire to ensure and make sure that I work my tail off to be as to somewhat ensure some success during my time here. So I was like, “If that means me being in the top 10% of my class, then that’s where I need to be for me to be able to get to where I want to go.”

Handel Eugene: So yeah, getting there definitely was a struggle. And I’m a Haitian American and I come from a Haitian culture, an immigrant culture where both my parents were born and raised in Haiti. My grandma had eight kids and she came to America first, and she sent for her kids one by one to come to the US and I show that, because you’ve got this very strong figure in our family, and you’ve got this hard work ethic that’s just embedded and rooted in our culture and nobody knows about somebody who is successful in the arts, and you tell them that you want to go pursue that. It’s really challenging and tough, because you want to make your family proud, and you want to make your parents proud, and you want to do something that they will respect and will support you in.

Handel Eugene: And, the fact that nobody knows somebody who’s successful, there was a lot of pushback on that because you’re hesitant to give your well wishes to something like that because… Yeah, it’s just an exposure thing, and even myself, for example, if I have a cousin who wants to go into the music industry, I’ll be honest, there’ll be some cause for pause, some hesitation to encourage them to pursue that at first, because all right, the music industry is great. It’s a creative field, but you also want to be aware and mindful and you’ve got to pay your bills and on one hand, obviously, you’d love to see them to be successful, but also, what are the numbers, what are the statistics is on the other, and for me, for my family came from a good place.

Handel Eugene: It was just a place of concern, and so it took me a while to eventually get to Full Sail because I needed my parents’ blessing because I respect them too much to go rogue and just go do my own things. I respect and admire my family and my parents’ opinion. Thankfully, I was able to like gather enough evidence. I think it just pushed me even further. Honestly, I wanted to make my parents proud, and I wanted to prove to them that, “Hey, your son’s doing this, and he’s going to be all right.”

Handel Eugene: I’m going to be able to put fo- there’s the whole “broke artist” misconception that’s prevalent in society. And, it forced me to do as much research as possible and be like, “Oh look, there’s this person over here who’s doing it and you can actually make a living doing it over here.” It’s like, “Oh, I talked to this person on the phone, he’s doing this.” I think it forced me to do as much due diligence as possible to ensure that the decision that I was making, was going to pay off. And having had to go through all those hurdles, and those uncomfortable conversations, and trying to convince people that the thing that I’m doing, I really believe in, and I’m going to be successful at.

Handel Eugene: When I got to Full Sail, college, I just had this burning desire to like make sure that, yeah, there’s some risk involved, but I’m betting on myself. And I want to make sure that that bet pays off as much as possible. So, I’m going to do whatever I got to do to make it during my time here. So, that meant working harder than the next person. I think you’ve heard this before, just being an African American in general, it’s been said multiple times, you’ve got to work twice as hard to get half as much. There’s not as many African Americans in my industry and that’s something that I’m definitely cognizant of, and it’s something that I was aware of, and I use that as extra incentive to be like, “All right, maybe the odds aren’t in my favor, but if I’ve got a chance, then I’ve got to make those odds work for me as much as possible.” And that’s why I just worked as hard as I can. I’m going on with a long tangent here, but.

Maurice Cherry: No, no, no. It’s good to hear that. I was really going to ask this probably a little bit later on about kind of where that ambition comes from, but I mean I think being able to speak on it from, like you said, the perspective of one, not really being exposed to it that much growing up, and it sort of being more of a hobby, but then also having your family that kind of wants you to go into something that’s more stable because motion graphics or design or whatever you were calling it back then wasn’t really something they could see as being successful. So, you had to prove it to them in a way, but you also have to prove it to yourself.

Handel Eugene: Yeah, I was telling my mom and dad, “Don’t worry, I’m going to be all right” without having done it yet. It was like, I don’t know for sure what the future holds and I’m taking a big risk here. And so, all those different aspects…And I’m thankful I learned this lesson early on, you can use that to prevent you from pursuing something, or you can use that as a driving force as fuel to push you further. And thankfully, I chose the route of allowing that to push me to go above and beyond during my time there.

Maurice Cherry: So, what is your opinion about, I guess calling it animation was kind of just put a big tie in a big bow, but what is your opinion about diversity in the industry? Like, what do you want to see more of in your industry?

Handel Eugene: Yeah, I mean, this goes without saying, but definitely more black representation in general. You know, especially like at the decision making level. I’ve had to navigate through this industry in this field being the only black individual in my class, for example, or working at a studio, or freelancing at a place, or such, and being the only back individual in the room. And it’s so funny, because when you do come across those individuals that look like you, they’re just like the most talented people I know. And, it’s like, “man, there should just be more of that around and we need to…”

Handel Eugene: So, that’s definitely something that I’d love to see more of, and I’ll tell you, I was listening to one of the previous podcasts and I can’t remember who I was listening to, but there was something that you said that really stuck with me and this is why I’m really loving the work that you’re doing is that, you’ll reach out to some people and maybe they’ll tell you, “No, I’m not in a position to come on the podcast yet”, or “No, I’m maybe not as accomplished, or maybe not as successful or maybe I’m”, whatever the case may be. And they’ll put these barriers on themselves and I love that you say like, “No, that doesn’t matter”.

Handel Eugene: You want to hear from people from all different aspects and all different levels and all different areas in their life. And I love that, because that’s like, truthfully, honestly, had you asked me, I don’t know, two years ago, or something like that to come on this podcast, I would’ve said the same thing. And, it’s because it’s something that I’ve learning more and more now that, just in general, I think it’s so true, because you don’t see as many people that look like you. So, therefore you’re more susceptible to like imposter syndrome, like if you’re the only one here, you wonder if you even belong. And that’s something that I had to struggle with and had to deal with. It’s one of the reasons why my voice is… Like, I was very shy, very timid, not very bulky at all, but thankfully, like that hard

Handel Eugene: Thankfully, that hard work and ambition I had in school, that never left me. When I got into the industry, I just continued working hard, working hard, and thankfully my work started to get noticed, and my work started speaking for me, because I wasn’t screaming it from the hilltops or, “Hey look at me.” I wasn’t doing any of that, but I was sharing my work was in one word and just doing good work started in having that start to travel and, people were liking my work and it was just so, it was just so humbling because more people started reaching out to me, especially people that looked like me and African Americans. I’m going to say, “Hey, I’m rooting for you man”. “Like I’m loving the work that you’re doing keep up the good work”. And it, before it was, oh these are just some compliments and like, all right, that’s awesome.

Handel Eugene: Yeah, I appreciate it. Thank you. But appreciate this, that and the other. But it just started coming, just the more my work has getting more visible, more people started reaching out. It’s like I love seeing what you’re doing. I love seeing that you’re doing this, that and the other. And it’s just like I just got back, I just got back from speaking at a pretty big conference, one of the bigger prop conferences, my personal favorite conference called Lift Fest and I got asked to speak this year and come on stage and man, I can’t tell you the reception that I got after giving a talk on stage from the people in the industry that felt underrepresented and it was like they’re just love seeing you up there. So what I, what I’m starting to do more of, and I’m not perfect at this, but what I’m starting to do more of is embracing that platform and embracing that voice that I have because I can use that and I can use that to encourage and inspire and represent.

Handel Eugene: Because you don’t, they don’t hear from us that often, and so when they do, I want to make sure that we represent, I represent myself and others and represent the best of what we can be in what we, and so now I’m more embracing that, that aspect because naturally I’m out of my comfort zone. I don’t like attention. I don’t want to be the poster boy, anything like that. Like I feel like that’s a lot of pressure, but I’m learning more and more, especially hearing other people’s testimonials and people reaching out to me, sending me emails out of the blue. Hey, I just wanted to hear about your experience navigating through this space because just I’m just being as, as, as African American in this industry, I wonder if you are feeling this particular way because definitely how I’m feeling and I’m wondering if I’m the only one, I was like, nah man, I’m going through the same, I’ve got the same thing going through, still going through the same thing.

Handel Eugene: And so I appreciate again, what you’re doing with this podcast because it’s giving a voice to individuals and making it, letting us know that it’s possible and that we’re out there and we can be successful in design and in this industry and that we’re all going through a lot of the same things and experience a lot of the same things.

Handel Eugene: So as I’ve grown into my career, I’ve realized that I’m not just doing this for me, but I’m doing this for people like me. And, and that’s just something that I’ve been embracing a whole heck of a lot more as I continue to progress. So I, if there’s an opportunity for me to speak and voice and speak out, like I no longer shy away from that because even though that is my nature and that’s my tendency, I no longer shy away from that because if I can use my voice to again reach somebody else and purse somebody else to pursue the arts or to step up to the plate or strive for greatness, then I almost feel obligated to do so.

Handel Eugene: Because this is the best work that I can do is having the impact on others and influencing others, especially people that look like me to strive for greatness and to continue pushing forward.

Maurice Cherry: Wow. That’s powerful to hear, man. I mean it’s, it’s interesting like you mentioned, because I would imagine a lot of the work that you do, you are sort of behind the scenes as it, as it relates to the work that you do. The work kind of does have to speak for itself. And I get those same kind of emails too, where people just reach out and it’s a an advantage point because sometimes they’ll look at you as if you’ve made it, but you’re also still navigating through the industry because as your profile changes or as the work gets out there more, it puts you in different rooms and different places and different scenarios and you’re still trying to navigate all of that. It’s a really interesting kind of paradigm.

Handel Eugene: Yeah, for sure. For sure. It’s interesting because just being, just being in some of those rooms where you’re the only one representing your background, that’s the, and especially like in those decision making rooms, especially in those high profile creative environments, those and such, and having the confidence to speak up, especially in those rooms, that’s something I had to learn to do. I had to, I was just speaking at Ben Fest as I mentioned earlier, and a good friend of mine who’s also African American, man, where did you get that confidence from to go up there on this stage? And it’s so ironic and funny to hear her say that to me because I’m not confident, this is something, this is something that I had to truly work on, work really hard on and break out of my shell and, really kind of overcome that fear of that.

Handel Eugene: I think it’s something that, like you said, it’s always, you’re always working on and as you progress through your career, it’s always a struggle and a challenge. And, and I think I, like I said, we’re more susceptible to the imposter syndrome just because of how underrepresented we can be. And it’s not even [inaudible 00:58:16]. Like there’s real barriers, there’s real gatekeepers who want to prevent you from getting to where you go. So having to not meet those hurdles is a real struggle. There’s been like subtle slights that I’ve experienced for sure where there’s rooms where I felt like I should of been in or meetings I felt like I should’ve been in or like, especially like client basing meetings where I was, I felt I could bring a real strong perspective and outlook towards the particular project at hand where that didn’t happen.

Handel Eugene: So, yeah. And, and again, like I said earlier, I think there’s two things. There’s two responses to that. You can either use that to kind of draw further into your shell, draw back further into your shell and, and, and lower your confidence. Or you can use that as fuel to your fire and use that as a, I wasn’t asked to be in this particular this room, then you’re, you’re passing up on an opportunity that could make you better. I’m going to go and take, continue to work on me and continue to develop myself to make my skills and my talents and undeniable wherever I go. You know? So, so it just pushes it for me, it just pushes me further to, I don’t want to, I’m not looking for, I’m not looking, I don’t have a big debtor. I’m not looking to like prove anybody wrong.

Handel Eugene: I’m trying to prove myself right. Because I know what I’m capable of, I know my potential and I’m always constantly, I’m trying to strive for that and reach that and wherever I go. So it’s just more fuel to my fire for me.

Maurice Cherry: What does success look like for you now?

Handel Eugene: I’ve got somewhat of a controversial response to that. It’s not really controversial, just more so a topic that’s not touched or talk about. But like for me in my career I’m fortunate, I’ve gotten the opportunity to work on some great projects and I’ve gotten to work on opportunity work on some high profile projects, films and such. Got to work for high profile clients and such. And now I want to, for me, and I’m not here by any means, but I, I want to make a lot of money.

Handel Eugene: Right? And that sounds, that sounds controversial, but the reason being is it because I desire money in it of itself? That’s not the reason I want to use money. I want to use the money I earned to buy back my time. At the end of the day, we trade our time for money, right?

Maurice Cherry: True.

Handel Eugene: In the form of a job, right? We trade the type of money, but yet, what’s more valuable, right? Time or money. Like most people would say your time is more valuable than money, right? And so if, if time is your most valuable resource, right? So then the more money you have, the more time you can buy back in your day. Right? I want to I want to spend more time with my family for instance. I want to spend more time pursuing creative endeavors that are important to me.

Handel Eugene: Right now. My most precious resource I have is being allocated to a job, which is the norm, right? That’s the norm of society. But I’m working hard to try and create an alternative lifestyle that kind of circumvents the traditional system that we have with what the traditional job and such. So, and I say that and I wanted to, I say that because we make money in this taboo subject, right? But it’s a topic of discussion we need to have more of and we need more talk more you talk about, especially in our culture in general. Again, I don’t value money in itself. Money is just a tool. It’s a resource we can use to buy or trade for something of greater value. Right?

Handel Eugene: So yeah, I’m just working really hard to find, try to find creative ways, trading passive income, residual income, trying to find these different revenue models that allow me to buy back my times, that way I can pursue projects that are important to me without having money being an issue.

Handel Eugene: So I want to talk about that, how that discussion, because a lot of people may not realize that that’s an option.I think people may only considered just having a job being the only way, to navigate through life. But I’ve learned that I’ve seen and observed different alternatives. So I’m working, striving again, not there yet by any means, but I’m working, striving to try and get to that point. I’ve like, I’ve made a step in the right direction already currently.

Handel Eugene: Right? Like for example, I’ve always said, and this is just me personally in my, my personal glove, I’ve always said I don’t want to, I don’t want to worry about how many vacation days I have left. That’s something that’s always been a goal of mine. And thankfully I’ve actually achieved that goal somewhat by being freelance now. And having put it like now the ball kind of is in my court, to where I can take as much time as I want off. I feel that though, obviously I feel that financially, but I’ve kind of taken a step in the right direction and creating a career that is in enough of a demand to be able to take time off and turn down work. So where I can pursue some things that I want to pursue that are important to me and make the impact that I want to have, spend more time with my family.

Handel Eugene: I’ve got a beautiful wife, a young daughter and a young son. And as I mentioned earlier this industry at times can be labor intensive, can be long hours and although it’s incredibly rewarding and I do enjoy it. When you’re working in a job, you are building somebody else’s dream you’ll work hard to create a business and a machine that’s a for-profit machine that’s building up their dreams. And I want to take that time and devote it towards something that I truly, truly believe in and want to work on and pursue and build up my own dreams and my own business, my own in part empire and such. So that’s something that I’ve been thinking of more and more so lately. In the past there were certain priorities that are important to me that maybe aren’t as important to me now.

Handel Eugene: And so that’s something that’s something that I’m currently navigating and currently trying to solve. And like I said, I’ve made some steps in the right direction. Hopefully in the near future I’ll be able to have that autonomy to be able to do that.

Maurice Cherry: I mean, speaking of your wife and your kids, how do you balance all of that? Like while still striving to do great work and, and staying relevant in everything in your career?

Handel Eugene: Yeah, absolutely. For sure. It’s an adjustment for sure. It’s a major adjustment. It’s funny how much time we take for granted and how much time was a luxury for me and not realizing it. Until you have, until you have kids. I said that very same thing when I had one kid and I was like, man, I took all that time, extra time. I took that off granted, but then when I had two kids, I said it over again. I was like, man, that’s like what I had one kid. I was like, I was taking all the extra time for granted man. Like even less time now.

Handel Eugene: So yeah, well it’s something that is a major adjustment and it’s one of those things I’ve constantly, constantly trying to learn about how I can use this precious asset as effectively and efficiently as possible, so that way I can maximize, when I do have those times to pursue things, I can maximize that time. So there’ll be things that I’ve, I have to decide and know what’s a priority. There’s a saying that goes don’t major in the minor things. There’s some minor things in my life that I’ve had to be like this isn’t worth the time commitment.

Handel Eugene: Like I have my time is a valuable resource and I have less of it now so I can’t allocate it towards some of these other things that are things. Maybe there’s some leisurely stuff that weren’t of incredible importance to me and my family is that I may no longer need to, to indulging, and so I’m being more and more strict and more tenacious about the different things that I allow to consume my time now, because it’s becoming, because again, my time is so valuable. Even down to every little aspect. Before, I felt the need to respond back to every email that came into my inbox, and I was realizing how much time that was being that was taking away from, from my, there’s this small little things in my life that I’m like, all right, is this, is this a valuable use of my time right now?

Handel Eugene: And so now I don’t feel bad for responding back to somebody like two weeks later because, that sounds terrible, but it’s the truth because, because I can’t respond back to every single email or every inquiry or right away, I’m not that bad. I’m not too bad. Maybe a week. But no, but I just being very, without touching on too many sensitive topics, but like social media is another aspect that I’m like trying to curve as well and all these other different aspects of that conditioner, even distractions that can utilize your time that you can be otherwise using product productivly. Because I want my family to be our priority for sure.

Handel Eugene: Like it’s my number one priority and I don’t want to compromise on that by any means, but also to, I worked really hard to get to this point in my career and I don’t want to let that subside, and I want to continue. I feel like the older I get, the more I progress in my career, the more ideas and more I feel like I have more ideas now that I want to pursue than ever. And I want to, these are ideas that I want to pursue and I feel like they would have a major impact and I want to work on work that, is greater than me and transcends me and Travis further than anything I’ve done before.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah, you want to be able to enjoy the fruits of your labor. You work hard, you want to be able to at the end of the day, be able to leave work at work and enjoy your family, enjoy your free time. So we’re at the end of the year also. The end of the decade. When you look, let’s say the next five years it’ll be 2025 before you know it really, you sort of mentioned already the sort of feeling that you want to have, but what sort of projects do you think you’d want to be working on? Like where do you see yourself in the future?

Handel Eugene: Yeah, absolutely. Hopefully in five, ten years or so. My career path has led to the opportunity for me to pick and choose the type of jobs that I want to work on without, I touched on this a little bit earlier, but that without money really being an issue. Hopefully I’m at a point in my career where I have that autonomy that allows me to be able to take initiative and don’t develop projects that are important to me and using my skills and God given talent for good for social issues, I’m working on projects that are bigger than me and make an impact and are meaningful because like it’s, it’s, it’s one of those things like in my industry, which I’m incredibly grateful to be able to earn an income and work for some amazing clients.

Handel Eugene: But maybe a pessimistic alternative viewpoint of what it is that we do is that we’re kind of glorifying products, or services and selling to consumers things that they might not necessarily need. And so if anything, I want to offset some of that by just working on projects that are meaningful, that are impactful, that are informative, that are educational and have a purpose and advocating change and raising awareness on particular projects. So, and that’s not even five, ten I, that’s actually stuff that I’m working on now, honestly, that I’m trying to, to pursue more of. And there’s always the whole money versus and time issue aspect of it, whenever you’re pursuing those jobs that necessarily aren’t for profit but they’re there for the good of society, so those are the projects that are like incredibly interesting to me and project that I want to pursue.

Handel Eugene: Because it’s interesting because as an artist, as artists were uniquely positioned to speak a language that the generation today speaks. We speak it fluently, right? And the language that degeneration today consumes, and there’s a real power in that and it’s a cool uncle Ben here to be like super cheesy, but with great power comes great responsibility. If you think about it, like just think about how powerful just, they think about Cambridge Analytica and how powerful having access to those resources and influencing individuals to swing an election that’s crazy and insane. And to think that’s how much power you can have just by advertising to two people, well what if we use that power for good too to advertise, and promote and push and encourage ideas that that need to be heard. So that’s something that I’ve been thinking of more and more lately and what I’m trying to pursue more of is just just pursuing those projects that are more meaningful and using my talents and designs for. Good.

Maurice Cherry: Well just so to kind of wrap things up here, where can our audience find out more about you and your work and everything online?

Handel Eugene: Yeah, absolutely. My website is in handeleugene.com and you can find all my socials on there and all my work and everything that it is that I do. And, yeah, I just want to say too, like anybody has any questions about, we didn’t, we didn’t go into all the different things, millions of things that I could have talked about. But I guess the biggest thing I wanted to leave too with your viewers, if there’re any questions about navigating this industry, like motion graphics, most of the design, even the creative industry just in general. Just reach out, reach out to me. My email is on my website and you can reach out anytime and, and I’d love to continue like discussing this further with anybody who’s interested in and pursuing this, this industry and just in general.

Maurice Cherry: Sounds good. Well handle Eugene. I want to thank you so much for coming on the show. One, not just for sharing about the work that you’re doing with Apple and other companies is as well as the work that you’ve done with, with Marvel and in films and everything. Your story and your drive I think or something which is kind of the core of what revision path is about. As it relates to showing that there are people that are in the creative industry that have the same passion and verve and work ethic to really create great things. They just don’t necessarily always get recognized. And so it’s important to be able to not only provide a platform for them to shine, but also, as you alluded to, just a few minutes ago to find ways to use those skills to better the world around us.

Maurice Cherry: A lot of the work that I think we do as, as digital creatives can be very ephemeral. You designed something really great and then a year or two later it’s been phased out for whatever the next thing is. And then you wonder, I put so much time and energy and effort into this thing that now is no longer existing. So how do you use your skills for something that can be more impactful? And I think your story and everything that you’ve had to share, it’s something that is a great thing for us to end up the year on. So, I mean brother, I really want to see where you are in five years. Because like I told you, I’ve been following you since full sail. I’m so proud of the work you’re doing. I really just want to see where you’re it in the future. So thank you so much for coming on the show. I appreciate it.

Handel Eugene: Thank you man. I appreciate it and thank you for all the work that you’re doing. Seriously, once I found your podcast, I immediately became a better person, a more informed person, and learned so much. Just from hearing from you and hearing from the guests that you’ve had on the podcast. I seriously, I recommend it to anybody that I come across that’s dealing with the same issues that we’re dealing with. And I can’t thank you enough for having done over 300 episodes, interviewing so many talented and amazing creatives in the industry and just making us more visible and making more people aware of our potential and, and what we can strive for and what we can do. Seriously. Thank you.