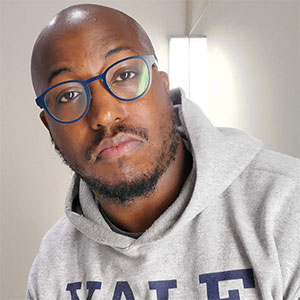

What do you get when you combine top notch graphic design and illustration talent, the intensity of punk music, and world class skills in facilitation? Why, you get this week’s guest — Kendall Howse! As we head into this festive holiday week, I couldn’t think of a better person to share their story and remind us of the power of inclusivity and empathy.

Our conversation began by exploring Kendall’s current work as a senior marketing designer at Red Hat. From there, we talked about employee resource groups at tech companies, the crisis of consumption in the Bay Area, and Kendall’s time growing up in Boston before moving out to California. We also discussed Kendall’s work as a facilitator with Frame Shift Consulting, his community work with Bay Area Black Designers, and his Black liberation hardcore punk band Mass Arrest. For Kendall, creating the space to thrive is key to who he is, and I hope that’s a message we can all take into the future. Happy holidays!

- Kendall Howse on Instagram

- Kendall Howse on Twitter

- “Five Years of Tech Diversity Reports—and Little Progress”, WIRED

Maurice Cherry: All right. Tell us who you are and what you do.

Kendall Howse: My name is Kendall Boo Boo Howse. I am a marketing designer for Red Hat, and I’ve been designing for a long time.

Maurice Cherry: How did you get started at Red Hat? What does your regular day-to-day look like there?

Kendall Howse: I’m on a really fantastic team that was called creative strategy and design, but we’ve just absorbed the brand team as well. I think now it’s brand and creative, but it’s a team of about 30 to 40 people including graphic designers, animators, filmmakers, 3D illustrators. It’s really a dynamic team.

Kendall Howse: Within that team, I do a lot of graphic design, digital graphic design and illustration, for everything from web assets to print assets to our major annual trade show conference called Red Hat Summit where we cater to about 8,000 attendees and do a full-immersive three-day experience with that. There’s a lot of variety to the work, which I really appreciate.

Maurice Cherry: Now, before that you were at CoreOS, which got acquired by Red Hat. Is that right?

Kendall Howse: Yeah. Yeah. At CoreOS I was hired. I was an employee in the 60s. I was the third designer. At that time, the design team was doing all of the marketing design and all the product design. It was a software company, one of the first companies in the Kubernetes space. We were doing everything from social media ads to conference booth work, but also doing the user interface to the actual product. After a little while we ended up splitting the design team into marketing and product, where I then became the sole marketing designer.

Kendall Howse: I was supposed to build the team, but we ended up doing a hiring freeze because, unbeknownst to me, we were in the process of being acquired. When that happens, you stop spending money. I then spent the final year of CoreOS as the only person doing all marketing and sales design, but that led to us being acquired by Red Hat, me being acquired by Red Hat. Then about eight months later, Red Hat got acquired by IBM. A lot of little fish being eaten by bigger fish.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. Has there been a big shift in the work or the work culture since the acquisition?

Kendall Howse: There has. CoreOS was a really small startup. I think in the end we had 130 employees, after four years. Very San Francisco, very venture capital, Y Combinator. A lot of hoodies. Young. Really young, too. Most of the employees, I would say, were under the age of 30. When we were acquired by Red Hat, Red Hat had been around for 25 years. Red Hat is based in Raleigh, North Carolina, so opposite coast, and was like 13,000 people, so a big cultural shift.

Kendall Howse: When we were acquired, as often happens, the majority of the original employees, within the first year, left for other opportunities. There was a massive shift of culture, not for the worse in any way. I mean, there’s I think appeal to a lot of people, the idea of working at a startup, but the thing about startups is it’s very touch-and-go. It’s very insecure. Whereas a big company…I mean, like a startup, you don’t have HR until you have to have HR, right? Where a big company like Red Hat has worked a lot of this stuff out literally decades ago, and so it’s a much more secure environment. It’s a much more fully realized idea.

Kendall Howse: Going from being a team of one to being on a team of 30. I’m someone who much prefers to work on a team. I’m really inspired by the work that other people do. I also really like contributing as much as I like creating. For me it was amazing to suddenly be on this big creative team. Culture change, yes. For the worse, no, definitely not.

Maurice Cherry: Okay. Now, as I was doing my research about Red Hat, I saw they have…it’s funny that you mentioned this, about these larger companies having it all worked out. They have a whole nine-page white paper that addresses culture, diversity and inclusion at the company. In that paper they talk about one of their five main D&I communities. One of them’s called BUILD, which is a acronym for Blacks United In Leadership and Diversity. Now, you co-lead this group, is that right?

Kendall Howse: I do, yep. Employee resource groups are I think a really important thing. When I was at CoreOS I had co-founded Blacks At CoreOS, which was our black employee resource group. There were three of us. We all worked on different teams and didn’t even live in the same cities. Just having that, being afforded the space and the resources to come together and advocate for ourselves and our community, was really important.

Kendall Howse: When we were acquired by Red Hat, that was the first thing I looked into. There was some trepidation from me being in the Bay Area, living in Oakland, walking down the same streets as the founders of the Black Panther Party. That spirit is still very alive in Oakland. Being acquired by a company out of the South was for me pretty intimidating, or I just didn’t know what to expect.

Kendall Howse: That was the first thing that I did, was try to see if they had a black employee resource group, and that’s how I found BUILD. BUILD, as I understand it, was Red Hat’s first ERG. It’s the pilot program. It started organically, where a few brothers who were software engineers started getting together unofficially and had their own IRC chat or some such. At a certain point…and I don’t know exactly how it developed…they were able to approach someone in the company and say, “We think that this is something that Red Hat should be supporting officially. It should be open to not just black employees but also allies as well, and should have some executive sponsorship.”

Kendall Howse: It’s great to be a part of this ERG, because it is the most established at the company. I think it’s about three years in, but it’s also the pilot program. We’re the ones who…there’s a lot more pressure…I would say…on us…but we are the ones who are forging the way for all of the other employee resource groups. I mean, now, like you said, we have five. We have a queer employee resource group which is hugely supported. We have one for veterans, one for indigenous people. I don’t know if we have a Latinx one.

Kendall Howse: I don’t know, but all of which is to say like it’s great to see that this is a movement. The employee resource group movement is something that’s growing, and my trepidation about working for this Southern company has shifted severely, because this ERG is really, really well funded.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. I’m thinking about what is the nexus point in a company where they decide that they want to do this. Because you said when you started it, CoreOS was a small company. BUILD was initially just three people. Do you think that there is a certain time when a startup should be taking this thing into consideration when it comes to diversity and inclusion?

Kendall Howse: Yeah. I mean, especially for startups, day one. I mean, it should be a part of the culture. We talk about diversity is something that tech companies and people who work in computation find really appealing, because it’s really quantifiable. I mean, it’s easy to say we have X number of a subgroup. Inclusion is the hard part, because it’s not measurable, it’s not quantifiable, and it’s not visible to the people who aren’t a member of the marginalized group that’s being included or excluded. My white manager can’t know if I feel included or not. I mean, unless she asks me, right?

Kendall Howse: I think when the D&I big push was happening in San Francisco five years ago, the focus was really on diversity and hitting numbers, but not about shifting culture in any way. That’s a top-down decision, which means it’s a lot of cis, straight white men, just filling their numbers, and that proved to be ineffective.

Kendall Howse: With employee resource groups, what you’re doing as a company is you are giving the people who are the marginalized group the resources to be able to advocate for themselves. We know, through community-building going back a hundred years, that’s the best way. To say, “You know what, I don’t know what, say, a woman from El Salvador needs to feel welcome and included in an environment. Why don’t I give her the tools and the resources to be able to start advocating for herself?”

Kendall Howse: In that way, we can build a more positive and inclusive culture, because then the ERGs too will work together. There’s five ERGs at Red Hat, but we’re constantly working with each other as well. Not only are we learning how to advocate for ourselves, but we’re also learning what our colleagues, who are of another marginalized group, also need.

Kendall Howse: I think that when you’re forming an organization, whether it be a startup, whether it be a Meetup group, whether it be a Slack channel or anything like that, you should be thinking that as early on as possible, like day one, for sure.

Kendall Howse: Honestly, I think if you start a company, your first black employee, be like, “Hey, do you want to have a employee resource group? What do you envision might be helpful for you? Like how can we open the door to more people like you, so that we can have true diversity and have people feel welcome being here?”

Maurice Cherry: It feels like there’s been a shift with that, because I remember. You’re talking about five years ago. I know that a lot of the language around then was about not putting the onus I guess on the employee, in a way, to do the D&I work, that it should be a top-down thing. Which I still agree that it should be, but now it seems like putting those resources in the hands of employees is a safer bet.

Kendall Howse: Yeah. I think you bring up a really good point there. I don’t know about you, but I as a black person have definitely been in a lot of situations where it’s been shoved into my lap. “Well, I don’t know, you figure it out.” It’s a lot of unpaid hours. It’s a lot of unsupported work, like where maybe the chief of operations is saying do this, but your direct report manager is like, “Well, you don’t have time to do this.”

Kendall Howse: I think the key to good D&I is executive sponsorship. It has to be supported at the highest ranks, so that your manager can’t tell you that you can’t work on it. Your PM has to pencil in time, because it has to be the company has to show from the top tier that it’s deeply dedicated to this work.

Kendall Howse: It can’t be leaving an individual or a small group of people to seem rogue, to seem, for lack of a better term, special needs. That isn’t the case. The executive leadership has to say, “No, this is a part of the core tenant of this organization, of this community that we are building, and including our customers. All of this is core to our values, and so we’re going to put in the time, the money, the resources, to make sure that this happens.”

Kendall Howse: Now, one interesting thing that happens in a lot of companies is the executives are still straight, cis white men, and so I don’t know of a single ERG…actually, I probably know a couple, but the vast majority of the ones I know of, including my black employee resource group, it’s technically led by a white man, because our executive sponsor is a white guy.

Kendall Howse: Now, I could see situations where that can be problematic, but in our case it’s actually great, because there’s an opportunity where I know that there are people. I mean, at this point there have been so many leaked Google memos that we know that there are people who aren’t a part of these groups that are really taking offense, and that are really having an issue with the fact of these groups. They just don’t understand the value and the necessity of these groups. To have someone like them saying, “Well, look, I’m okay with it. Not only am I okay with it, I sign off on it. I support it. I’m facilitating this thing.” I think that that representation is really important as well.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. Five years ago, to that point, you said earlier there were a lot of these really big tech companies…Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft…that were all about, “yes, we’re going to put our numbers out there and we’re going to try to bring in more people of color to diversify our workforce.” I think all of these companies have certainly had great business success. Like Microsoft bought LinkedIn and Github, Facebook doubled their monthly active users. They’ve had all this business success.

Maurice Cherry: Then when it comes down to diversifying their workforces, the percentages are still single-digit, plus-or-minus rises or falls. You would think that if you put all of that money and resources into this, if after five years you didn’t get anywhere, you would think that someone probably wouldn’t have a job. It doesn’t seem like there’s any consequence for not diversifying.

Maurice Cherry: I even know in some circles…I mean, this conversation I think was coming up a lot last year…where people, mostly white people, were vocally being like, “I’m tired of hearing about D&I.” Like, “Oh, how convenient.” “I’m tired of hearing about diversity.” “Oh, that’s nice.”

Maurice Cherry: The inclusion part is…I liked that part where you said that diversity is quantifiable, inclusion is not, because it’s all about once you have those diverse hires in the door and they’re working for you, how do you keep them? What does that attrition data look like, once you’ve brought these people on? It seems like it’s probably falling in a lot of these companies.

Kendall Howse: I think too that a lot of these companies…like imagine being on a product team, where you’re shipping constantly and things. You’re working in scrum, you’re doing these three-week sprints. There are real milestones that you’re hitting constantly, right, and everything is deadline-driven. Then you have this vague thing called D&I that doesn’t have a goal, not a clearly-stated goal. It doesn’t have an established timeline.

Kendall Howse: It’s just this vague thing, that a lot of people…there’s so much eye-rolling, of majority-group people and minority-group people. Eye rolling, like, “Ugh.” “Oh, yeah, I went to your website. It looks like you have one black employee, but you made sure that she’s in every single photo.” Like a lot of that eye-roll, and I think that…I mean, I blame the leadership. I blame the lack of direction. I have not been in the boardrooms where it was decided that a lot of these companies were going to focus on diversity and inclusion, and really diversity. To be honest, no one was talking about inclusion.

Kendall Howse: I don’t know exactly what prompted it, but there were these things that were happening, these scandals that kept hitting the news, that were terrifying people. Uber was the first one that I remember being really big. Google I think was next. There’s that, “Oh, we have to do something about it,” but there are all of these stories and things I experienced myself where maybe somebody comes in and gives a slideshow, and says like, “It’s really tough to be a woman in the workplace,” and like…and then, okay, what do you do? One company I worked at, they just set up a Slack channel called Diversity, but there were no [inaudible 00:17:05] and there were no guidelines. There was no mediator. There was no expert. There was no…there was nothing.

Kendall Howse: There were some horror shows that occurred, and then there was just a lot of like really well-meaning people really hungry for solutions, wanting. I mean, like straight white guys who were like, “How do I help? How do I advocate? How do I become an ally?” There was no one there, and no system in place to help guide them. It doesn’t surprise me at all that there are people eye-rolling. I remember one time standing up front of the company at the Monday morning all-hands check in.

Kendall Howse: My colleague and I, who is a wonderful designer, she and I got up and were giving a D&I presentation, and this is pretty early on in my D&I work journey. I just remember one of the engineers who does customer support…so he’s a problem solver, he’s solutions oriented…says, “Well, how many black people should we have?” It was like, “I don’t know,” you know what I mean? He wanted to know what the goal was.

Kendall Howse: I was so at the beginning being like, “Oh, we need to open the doors,” but he was asking to what ends. I think that if solutions-based people aren’t given a goal, then it’s nothing. It’s nothing. I mean, it can just sit in the ephemera, just hover in the atmosphere and just never been taken seriously, because there’s nothing to solve against. You’re not trying to beat anything, beat a deadline, beat a quota. It’s just…it means nothing.

Kendall Howse: When you take a lot of these companies where their mission statements would be so vague or fluffy, where it’s like, “Change the world with positive influence.” You’re just a grocery delivery app. How about just [inaudible 00:19:14] groceries to people efficiently? When you already have these vague notions, I think a lot of people just think of it like marketing-speak or think of it as just like it’s bullshit.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. I wonder certainly, I think, as we’re going now into a lot of companies starting to partner with other organizations, or like I know Google most famously. I think it was back in maybe 2015, 2016, they did like this partnership with Howard where there’s Howard West out at Google’s campus, and so some of the freshmen from I think the computer science department were able to go there and learn and study from Google engineers.

Maurice Cherry: I’m interested to see how some of these programs, what the dividends are from some of them, because a lot of them I feel like have certainly been started in the wake of these horrible numbers that are coming out with workplace percentages of diversity. Then like you say, there’s also these horror stories of people that have worked there and then it goes south. It’s in TechCrunch, it’s in Mashable, it’s in USA Today. You’re hearing about it, and I don’t know really how much of an effect that has on hiring. For some of these companies…to be honest, I think Facebook probably might be one of them…they might just brush it off, like, “Oh, okay. What’s next?”

Kendall Howse: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think the reality is, around here at least, I don’t think that there are people of color or queer people or queer women of color. I don’t think that they’re turning down jobs at Google because they’ve heard it’s a toxic culture. I’m sure that there are some, but the reality as I see it is that there’s been…the pipeline argument has just been around forever, and I’m of the opinion that it’s been disproven over and over and over again.

Kendall Howse: People hire themselves, in one way or another, so frequently. They want to hire from the program they went to in school, because they know those professors. They know what’s being taught, they know what the challenges are, and they know what the results. Or they’re hiring from the company that they worked for last. What was the team they were on at their last company? Well, they’re going to poach whoever they can. They’re establishing their own pipelines the whole time.

Kendall Howse: I think that, to really have a diverse enough space that diversity no longer is even a topic, you have to fundamentally change. You have to break up the pipelines, and so it’s going to happen on a lot of different fronts and it’s going to happen at every single level, from the individual contributor all the way up to the CEO. Everybody should be, in one way or another, focused on it, in order for it to work in any sort of timely fashion.

Kendall Howse: Some of these programs, like working with Howard, yes. I love that about BUILD at Red Hat. They’re down south, they’re in North Carolina. They are in HBCU heaven. There’s so much outreach going on in partnership with the local HBCUs. That is how we change pipeline.

Kendall Howse: A thing that I was working on at CoreOS…we were acquired before I was able to realize it…but our intern program was building, building, building. It was getting bigger and bigger. It was all from the same university, or one of three universities. It was where the CEO and CTO went, together, where the head of one of the engineering teams went himself…he went to Rochester, they went to Oregon…or Stanford. That was it. It doesn’t get more homogenous than that.

Kendall Howse: I mean, so we were just getting like 17, 18 of these interns in, and they all were…they all knew each other. They’re all the same. We’re in the Bay Area, where there’s this crisis where the tech industry is eating up everything, and you have an area that had such great black representation, Latinx representation, Chinese and other East Asian and Asian Pacific Island representation, yet none of these people are working in what’s becoming the only industry in town.

Kendall Howse: When I was a kid, especially immigrant parents, black parents, would be like, “Oh, you’ve got to grow up and be a doctor, or you’ve got to grow up and be an engineer.” Now it’s like you’ve got to learn to code. It’s not a generational thing, because most of these people, it’s not like their parents had been doing this stuff. It’s like their parents were building websites in the ’60s. The industry the way we know it didn’t exist.

Kendall Howse: Here they are, trucking in all of these interns from all of these places. Meanwhile at their feet, literally, like on the ground floor of the building, is a cafe full of people from the neighborhood, from the area, that are working there with absolutely no access.

Kendall Howse: That’s when I was pushing it to try to partner with some of the local colleges, of which there are many, and try to get a pipeline built in. It’s like, “All right, for every two Rochester kids you bring in, bring in one from Oakland. Bring in one from Berkeley. Bring in just one, because there’s no reason to believe that your own path that you’ve taken, your own experience, is the only legitimate one or the best one.” It’s that type of thinking that really limits the opportunities for others.

Kendall Howse: Will working with Howard make the company better? I don’t know, but is it a good idea? Absolutely. Absolutely. I support it. These programs shouldn’t be left to stand on their own. They should be a part of a fully-supported, fully-fronted …

Kendall Howse: A part of a fully supported, fully fronted, I guess, war on homogeny. Wow, that sounded really dark.

Maurice Cherry: I feel you’re coming from though, like you have to be able to utilize those resources if you want to make that change.

Kendall Howse: Absolutely. Yeah. And it’s wild to me that like HBCUs aren’t even being talked about around here or women’s colleges. It’s not, it’s like…

Maurice Cherry: Yeah.

Kendall Howse: I just wish there were more black people at Stanford. Well, I mean I wish that too, but there are lots of other colleges to look at. You just… You got to go out, you got to you got to put in the work of finding people.

Maurice Cherry: I remember doing some consulting with, I think this is with Vox back in like 2015, and I had just made mention like, “Oh, well have you all done anything at Howard?” And it was like, you could see people’s minds explode. Like, “We never thought of that”. I’m like, “Really, it is not that far from y’all. Like you’re headquartered in DC. Like it’s not that far. Go to a career fair. Talk to some people”. It’s, I don’t know, it’s interesting. Just to kind of switch gears a little bit here because you mentioned the Bay Area. Did you grow up in the Bay Area?

Kendall Howse: No, so I lived in… I grew up in Boston, in and around Boston, and I moved to the Bay Area 11 years ago. It was a 2008, I moved to the Bay Area.

Maurice Cherry: Okay. So growing up in and around Boston, were you exposed to art and design kind of in your childhood?

Kendall Howse: I was, so I was raised a musician and my brother, who was a couple of years older than me, is a phenomenal illustrator. He was that kid that was a little… He was shy and so he’d be in the corner with a pen and a sketchbook at all times and now he’s really kicking off his career as an illustrator. But he’s just unbelievable. And so I was always… He was my older brother and my hero. I was very influenced by what he was doing. And probably I started going to shows where was like 11. Joined my first band when I was 12 and at that time, this is 1991, we were broke. Everyone that I knew that was from the area, we were just poor kids. And so when we were starting our first band, somebody had to make a t-shirt, somebody had to design the tape cover, somebody had to make the flyer and being influenced by my brother and being kind of aesthetic minded, I was oftentimes the person who was doing it and I loved doing it.

Kendall Howse: And so I was doing it for myself at 12, 13, 14, and then other bands are asking me to do designs for them. And then record labels and tour managers are having me do posters and t-shirts and record covers for them. And so that kind of kicked off design as a hobby/passion for me for years. But I didn’t have, by my estimation, I didn’t have access to college. And so this was a side thing that I did for a long time, for about 20 years, 15 years, something like that. And it went from then bands, labels, tour managers to then small brands, coffee shops, tea brands, things like that, and then I just found that I was getting more and more into it and then… And just devour whatever books I could read on the topic.

Kendall Howse: Whenever I met a person who was practicing design, who was also interested design. It just, it really like blossomed for me into, really, obsession. And then I hit the point where I was tired of being a barista/bouncer/bike messenger/a chef and just really wanted to focus on the design. But for me I was a pretty latecomer. It wasn’t until my mid twenties where I was able to focus on design directly and with the school and was able to refine my craft.

Maurice Cherry: Nice. It’s interesting how I think a lot of designers tend to get into this through music in some sort of way. I was actually, I interviewed Erica Lewis. We’re all in the same slack group. So I interviewed Erica Lewis and she’s a jazz singer and she was talking about how she got into doing design through like being exposed to like posters and album covers and stuff like that. And it got me to thinking actually about this, as we’re sort of talking about design a little bit here, how websites have all started to kind of look the same. I heard this in a podcast from Adobe, they have this podcast called Wireframe and so one of the latest episodes, they were like, “Oh, you know, all websites are looking the same,” with the rectangular hero image and the parallax scrolling and how in the early days of design, like in the, I don’t know, late nineties, two thousands, et cetera, probably a little earlier than that, a lot of design was very free form because you got on the web and you realize you could make anything.

Maurice Cherry: A lot of that stuff, at least from when I remember, back in the old days of table based design, you basically made something in Photoshop and you export it in slices and it came in these tables and you uploaded it and that was your website. And you could really kind of go wild with how it looked because you weren’t… I guess you weren’t really designing so strictly within the concept of a grid, even though that’s what tables are. You were able to kind of be a little bit more free form, but now that everyone is kind of speaking the same design language through, I would say, bootcamps and education and just the way companies are now taking design more seriously. Now everything is starting to kind of look the same. Which is, it’s an odd concept when you think about it because, I would say, digital graphic design is still a fairly new thing.

Kendall Howse: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, especially compared to poster design, for instance. But I think, I feel like I’m of the last generation of the LP, where as a kid, I would get a record and put it on, and this 12 and a half by 12 and a half thing, sometimes with a the poster inside. I would just sit there for hours and hours and hours looking at this art and looking for the Easter eggs. And it was okay for there to be hidden elements. It was okay for there to not be immediate comprehension, that you could have… You could have a period of your brain trying to unlock the message. And I think early days of web were very much about that. I think there was this idea of personal expression, much like jazz poster art, for instance, where you could break rules or bend rules at least.

Kendall Howse: And that was really exciting for designers. I think the big difference is, it’s not necessarily as exciting for the viewer on the web because I think that most of the web, we’re using very differently than poster art or LP art. And I think that when I talk with newer designers, I think that I spend a lot of time trying to talk about separating the ego from the work because you’re not designing for yourself and it’s not necessarily representative of your personality. You’re aiming for clarity, you’re aiming for accessibility, you want, you have a client that has a message, a point of communication. And so you want it to be clear. You don’t want the brain to have that time of trying to decipher the message. You want it to be right up front.

Kendall Howse: And so it makes sense to me. Though, I know that for some creative people it’s a real bummer that the space looks so, I guess kind, of prefab. But from an accessibility point of view, it makes a lot of sense. And I think that that’s where the web is maturing in so many ways, where it’s not just… Early days of web was just backend engineers that knew HTML and putting things up and a lot of it is just, “Oh, it’s just good enough,” or, “Oh, you can read this,” but it’s like, “Oh really? You did like yellow type on a black background? Like okay, like that’s not necessarily the best answer”. And so as much as I bemoan, the lack of creativity, I applaud the increase in accessibility and more understanding that there are just so many different types of people that are trying to get the information that meeting them where they’re at makes sense.

Kendall Howse: Now because of that is why I designed professionally, but then I do my poster art and stuff on the side because when I’m designing, I’m not designing for myself, but when I’m doing my poster art or my own band’s work, that gets to be completely my ego. That gets to be my complete expression of my own personality and I get to keep the two separated, which I think is important.

Maurice Cherry: Now, when you were deciding to do this professionally, you said you kind of came into it in your mid twenties was your family supportive of you going into this route?

Kendall Howse: Yeah, totally. In fact, my stepdad is a graphic designer himself. He runs Anchor Ball Studios and he was a great resource for me too. Yeah, I was [inaudible 00:34:53] my first couple of years I did a lot of freelance work with him and so really helped me learn about that separation, really helped me learn the difference between designing a punk flyer and expressing myself and my subculture and speaking in an insular fashion where I’m speaking to an existing audience, as opposed to something on a much broader platform where I’m trying to attract new audience and I’m trying to attract as many people as possible. So that was huge for me. Huge for me. And then again, my brother is an illustrator. We definitely have blue collar upbringings and my brother actually has only gotten this, starting his career very recently. He’s a decorative plasterer for 20 something years and now he’s getting to focus on illustration. So my family, I’ve been really, really fortunate. It’s a small family, but a very supportive family.

Maurice Cherry: What was your early career like? This is pre-Red Hat, pre-CoreOS. What was that early design career like, when you look back at it?

Kendall Howse: Hungry, scrappy, desperate. Yeah, I started off freelance. My goal was to eventually get into an agency was my hope. And so I was by Kruger, by Crux, I was just trying to find freelance clients. And so I was fortunate to do a work with Anchor Ball and that was probably 20% of what I was doing. And I was just out there hanging up business cards, shaking hands, meeting people. I remember I played, my band played a show. I played a festival in Oklahoma City where I met a woman who… We ended up at the airport, going our separate ways and she was like, “Oh, well I run like demand generation,” or, “I work for a demand gen company. We’re always looking for design”. And next thing I know, it’s 20% of my work now is doing design for her.

Kendall Howse: Like it was anywhere I could find somebody that was willing to pay. And I did that for years. I did that for years and it was hungry work, especially in November, December. A lot of companies, so that they can post fourth quarter gains, one of their tools is they just don’t pay any money out. And so you can be doing 40 hours of work a week for a company through November and December and they’ll just stop answering your calls about pay because they’re going to pay you in January, but they need the work out of you and… But they’re not going to pay you. And I had some really lean months and really scary months. Yeah, it was a grind. It was a grind every day.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. I remember when I first started just doing freelance work, I was still in college. I think I started doing freelance for other people and yeah, those early clients were… It was tough because one, they already, at least for me, they were like, “We don’t really take you seriously because you’re not in design school”. Like I was in school studying math. No one was looking at me. Even though I had design stuff under my belt, people were like, “Oh no”. And I would have, I mean my clients, my early clients were rough man. Me and I had this one client who only wanted to pay me in Sunday dinners because she didn’t really… It’s not that she didn’t believe in paying, she just preferred to pay in a non-monetary fashion. We’ll just put it that way. She was like, “You can come over and I’ll fix you a plate”. And I’m like, “That’s not really… I mean I have a meal plan at the caf. I can just get whatever,” but…

Maurice Cherry: And then even when I started my studio years and years later, my first few clients I had would really be trying to stiff you on just the most minuscule amounts, like 200 bucks. Like dude, it’s $200 worth of work. Now granted I probably shouldn’t have been doing that little amount of work, but I had just started my studio and I was hungry to just get a few client names under my belt and it was rough.

Maurice Cherry: I ended up landing into working on a political campaign, I’d say maybe about a year after I started my studio, which really came at the right time because I was looking for jobs after that. Before that I was like, “This is not working out. Like I thought it was”. I had quit my job kind of in protest. Obama got elected and I was like, “Yes we can”. And I already hated the job that I was working at and I was like, “I’m just going to do it. I’m just going to put it out there and try to do it”. And yeah, those first few months, really that first year was really rough and my mom was sending money and she was like, “You know,” you can put your pride to the side and just like get a job. I was like, “No, I’m going to do it”. And I landed in this campaign and it ended up working out from there. But those early scrappy days man, something has to be said for just the time where you will just do any kind of work just to get the money.

Kendall Howse: Oh yeah. Oh, and it may talk about like removing the ego. There was just so much times where, as designers, we’re essentially problem solvers, right? So I will use my training and my skillset to come up with a solution. But so often these people, they’re bringing you a solution and not only are they bringing you a solution, but in their mind they’ve already solved the problem and they know how much that that solution is worth. And so they’re like, “Well, could you do this thing? I already have an idea of what it should look like and I already have an idea of how much it should cost and how much… And because it only took me five minutes to come up with it. I think I should only give you $10,” and there was just… I was just eating so much crow being like, “No, that’s not the way to do it. That isn’t… I can show you research, I can show you best practices, I can show you examples and show…”. They don’t care.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah, clients, they’re not looking at that. They don’t care.

Kendall Howse: No, and especially, I think that… I mean there’s a ton of devaluing of design. It’s something that comes up all the time that, as designers, we’ve talked about all the time, but it’s this idea that people think that it’s just a gut shot. It’s just all intuition and it doesn’t occur to them that there is research behind it, that there is method and best practices. And so there’s a lot of notion of like, “Oh well, my nephew or niece, they are good with colors”. That’s what that means, you know what I mean? Or their outfits always match or something like that.

Kendall Howse: And so there’s a lot of that tug of war before… As a designer you have like a realized sense of self, a realized sense of realistic worth, worth of work, not worth of person. We’re all worthless, like are… Not worthless, priceless. We’re all priceless. But a lot of that tug of war where you don’t want us to know. Most of the clients that I did work for, I wouldn’t do work for now. Clearly the way you look at design and the way you look at solutions and what you want out of the designer is actually not what I provide. So, best of luck. I wish the best for you, but we’re just not made to work together. But back then it’s like, “All right. Yeah, no cool. Only $10?” Or, “Only a Sunday dinner?” Like, I’m not hype on it, but I got to eat.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. I remember I heard from a designer one time at a conference that I think it was something along the lines of what you were saying about kind of the speed it might take to do something. If you do a job and say, I don’t know. If you can look at a job and say, “I can do that in an hour,” but the reason you can do it in an hour is because you spent five years learning how to do it in an hour. So you’re really paying for the years. You’re not paying for the hour.

Kendall Howse: Right, right. I mean isn’t it-

Maurice Cherry: And company. Yeah. No, I’m saying companies look at… Companies, I think clients too, they just look at the hours as if like that’s the discrete amount. Like “Oh that’s what the cost is? Well how many hours is that?” And it doesn’t break down that discretely that you can just take the cost and chop it up in that way. Because it then commoditizes design to the point where you think, I guess anyone can do it and it’s not really the case.

Kendall Howse: Right, absolutely. I mean… What is the… Is that an old story? I don’t know if it’s even true or not, but about Picasso later in life. Having like a… A woman asked Picasso to draw something and he-

Maurice Cherry: Yeah, I heard that.

Kendall Howse: Just something very simple and she’s like, “It only took you five minutes,” and he’s like, “My dear. It took me my whole life”. I think that there is real value to that. I mean someone like Aaron Draplin for instance, when he does a tutorial on how to do a logo in five minutes. I feel like what he’s trying to show is that anybody can learn to design and I 100% believe that. I don’t think that it takes inborn talent. I don’t think it’s inherent, I think that anybody can learn the craft of successful design. 100%. I think though that there are some spectators who see Aaron doing that, that think, “Oh, well I could do that,” in a dismissive way. The whole, “Like if my kid could draw this, then it’s not art,” that bullshit line.

Kendall Howse: And so not to get in the weeds about this, but I think that people are… Because it is an hourly charged thing so frequently, there’s a lot of people with a dubious attitude that are like trying, without knowing what actually goes into it, they’re trying to figure out how you, as the designer, as the hired person, are trying to pull one over on them and they [inaudible 00:44:43] mistrust. And that’s why like I think it is important to, when you’re specking out a project, to put as much information as possible. Like “Oh, like first thing I’m going to do is like this many hours of research, but here’s what I’ll be researching. Here’s what about looking at here’s how much time I spent putting together this brief and this outline”. Because it’s tough that so often as a designer, especially earlier on in your career, you have to be constantly defending the value of design. Constantly. But that’s part of design. Part being able to speak to your design, being able to build the value into it and express the value. Unfortunately, it’s a part of the part of the games.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. Part of the game. I feel you. Now, aside from your design work, you also do some facilitation work with Frame Shift Consulting. I learned about that because at Glitch we had Valerie Aurora, she gave an ally skills training to us earlier this year and I was looking at the website. I was like, “Wait a minute, I know him”. How did you get started with them?

Kendall Howse: So when I was at CoreOS, the CTO, Brandon, of CoreOS, is a great guy and he had been… When he was going to Oregon, he was a Linux developer and he met Valerie as one of his Linux mentors. She was a developer for the Linux kernel, which for developers, is a very impressive thing. And so at the same time she was doing the ADA Initiative. She was part of the Geek feminism. She was doing a lot. She was already doing advocacy work within her direct tech communities. Really for women, fem-identified and queer people. And over time she stopped developing computer software and really focused her attention, a hundred percent, into Frame Shift Consulting and into this facilitation work. And so Brandon had her come and teach her ally skills class to our small company. And I got so much out of that workshop as an ally and as a member of a targeted group.

Kendall Howse: It was really clear, it was really concise. And watching the discovery process, I’m in a room of, maybe, 30 people, nearly every single one, nearly every single one, CIS straight white man, but it’s a volunteer only program. So it’s people who wanted actual skills to be better at advocating for people around them. This is the inclusion part. Here’s the difference between diversity and inclusion. Inclusion is how we work to make ourselves and each other feel comfortable, invited and welcome. And so it was great seeing them actually learn these tools, and myself as well, learn these tools. And I learned things about my own privilege and privileges that I didn’t know before.

Kendall Howse: And so after that workshop was through, she then came back and did a code of conduct development and enforcement workshop with us and I was doing a lot of event work at the time. And so I got to work with her again. And then she had announced that she was doing a train the trainers and CoreOS paid for me to go and get trained. And since then, Valerie and I have developed a friendship and a real great kind of idea sharing around this stuff. And so it wasn’t long before, it just made sense that I love the work so much and it’s so important to me, that I just come on board with Frame Shift and start facilitating the workshop on my own, which has been a really great experience. Yeah.

Maurice Cherry: Nice. And now also, I mean aside from your design work, you’re doing consultation, you are also helping out with the design community sort of in the Bay Area. Is that right? You’re, co-leading or co-chair of a group called Bay Area Black Designers, which is founded by Kat Vellos, who we’ve had on the show before. How have you started to see the Bay Area kind of change in terms of the design community since you’ve been there?

Kendall Howse: It’s changed quite a bit. One of the things that’s interesting about the Bay Area, I think, I don’t remember, maybe it was Mike Montero that heard point out that in places like New York, design is its own community and its own industry. Whereas in the Bay Area, design is very much a niche of the tech industry and the tech community. So whatever we do is kind of predicated on tech and that solid innovation, which really, I mean it changes a lot. So right now design, is huge in the Bay Area. I would say it’s primarily UX design. They get paid the most and there are award-winning UX design teams at most of these major tech companies. I’m seeing…

Kendall Howse: … these major tech companies. I’m seeing that design is being more readily accepted as a worthwhile thing. But again, UX has a lot of quantifiable aspects to it, right? Resourcing gets so much hard data back, whereas graphic design is much more nuanced. So, the difference between a graphic designer and a UX designer in this town is probably about $80,000 annually.

Maurice Cherry: Wow.

Kendall Howse: Yeah, it’s pretty dramatic. It’s one of the reasons why I don’t attach the word graphic to my design title. So when I discovered the Bay Area Black Designers, which Kat had started at about two years before I did, I was working at a tech company. I was one of the only, if not the only black person there. I was the only black designer I knew. I did not know a single other black designer.

Kendall Howse: This was around the time of, I want to say it was pre-Ferguson, but it was the month, the year leading up to between Oscar Grant and Michael Brown, Oakland was on the march. We were marching all the time. We were out in the streets, we were being teargassed by police, chased down. This was my reality after work and the horrors I was facing. Then I was going into work with these 25 year old guys that just … it was just across the Bay in San Francisco, but it was a world apart.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah, yeah.

Kendall Howse: It was incredibly isolating, incredibly isolating. I remember one day I was just really, really frustrated and I Googled black designers Bay area. Well, thank goodness Kat Vellos has her SEO game on point, because it popped right up. A week later or two weeks later, I was at my first meetup and was able to meet all these amazing black designers. What I noticed right away was none of us were from the Bay Area.

Kendall Howse: It’s grown from there. I mean, there’s now, on paper, there’s around 400 members of Bay Area Black Designers, and that coupled with the employee resource groups, a lot of the ERGs, Autodesk for instance, has a great black ERG. Salesforce’s ERGs are unbelievable. They’re so well-funded, well-supported. You have people like Rachel Williams who is just an amazing DNI leader.

Kendall Howse: They get us all together in these rooms. I mean, gosh, we got to be in a room with Issa Rae and Ryan Coogler two weeks ago, thanks to Salesforce. It’s all of these black professionals in tech, almost none of us are from the Bay area, which tells me that we’re still not supporting the area. That’s really important to me, because a lot of the older folks my age and older in BABD started as print designers and pure graphic design, typography, things like that, and haven’t had the opportunity or the means to shift into digital design and are being left behind, which is a real tragedy.

Kendall Howse: So, I mean, even like Mike Nicholls who does Umber Magazine, which is a blessing to our community.

Maurice Cherry: Shout out to Mike.

Kendall Howse: Shout out to Mike, all day. That itself is a tool for him to stay relevant, and it’s a tool for him to stay visible. Because otherwise as an analog illustrator and a typesetter, there’s just not space for him. So I am seeing more black faces in the crowd, but I’m not seeing more open faces. I’m not seeing more San Francisco, Richmond, Vallejo, the Bay Area isn’t being represented. That’s terrifying to me, because we’re seeing an eradication and a replacement of entire communities, at a scale which I’ve never seen before.

Kendall Howse: So, I would say that’s how I’m seeing design change. But also, design is so popular and there’s a lot of self-aggrandizing, self-back-patting that I see happening. I was a member of the San Francisco AIGA and they did a mentorship program about two years ago. I remember I signed on to be a mentee, because I’m not done developing my career, I’m not done developing in my skillset.

Kendall Howse: I remember one of the mentor, mentee mixers, talking with a guy who was probably, I would guess 23 or 24, very cocky, very self-assured. He was like, “Oh, I’m here as a mentor, I’m a mentor.” I’m not going to begrudge anyone. I mean, there are brilliant, very, very young people everywhere, so it’s not unreasonable to think that this guy could be a mentor.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah.

Kendall Howse: But the way he was talking was just so cocky and self-assured. Then the more and more he talked, he’s like, “Oh yeah, I’m a creative director.” I was like, “Gosh, wow, you’re a creative director at your age, that’s really impressive.” But then it turns out it’s because his brother is the founder and CEO of the startup. There’s only six people at the startup and this person is pole vaulting over a whole career path. I’m like, “Okay, well, where’s your mentee?” “Oh, I don’t know, I don’t know where she is.”

Maurice Cherry: Interesting.

Kendall Howse: She is just out of college, she’s 22. She’s looking for real development, real assistance, real anything, and this dude is not … I realized that he was much more into this idea, this persona of the designer, of the creative director. In doing so, in my opinion, was doing this really great disservice to this woman of color who’s just finished school, is a member of AIGA and is looking for development.

Kendall Howse: That, I think, for me it was a very San Francisco moment, where there are great swaths of people … of course, there’s incredible talent in this area, and I don’t want to take away from that. But there are also a lot of people who think of designer as more of a lifestyle and are just getting in these rooms where they’re just patting each other on the back and it’s being like, “We’re the best, we’re the best, we’re the best.” That’s disheartening.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah, I see that a lot on Twitter, which is why I really am not on design Twitter a whole lot, because I see so much of that. Designer as a lifestyle sort of thing, where they’re not really giving back to the community in any sort of way, they’re just providing unnecessary snarky kind of … I see that a lot. I see a lot of that.

Kendall Howse: Yeah, look at when any company rebrands. Suddenly everybody is an expert in design and it’s just finding new snarky ways to really devalue something that took years, right? Your hot take doesn’t matter, there’s a whole team. You don’t know what they were solving for, you don’t know why they changed it. There’s a lot of that that goes on. Then also, there’s, like you said, giving back to the community.

Kendall Howse: I remember I think about five years ago, there was a group of tech people who had moved to Oakland and they were like … this, I would say, the era of app building as a career. They were like, “We got to get together with the community of Oakland. We’re the new people, we’re the newcomers, we have to give back.” So we’re going to start meeting at city hall and we’re going to develop things for the community.”

Kendall Howse: At that time, Oakland was very black, very brown and very white, but also very working class, very poor. There were a lot of struggling communities at that time that could have used a lot of help from people with means, with access, with money. What this group did was they developed an app to make it easier to call the police. Black folks don’t need that. Black folks, the Projects don’t need that, the Arab communities down in the Acorn and lower bottom, it couldn’t be further from what they need.

Kendall Howse: What these people did is they walked in and said, “Well, what do I see missing compared to what I’m used to? Oh, there’s crime? Let’s not try to chip away at the [inaudible 00:58:42] reasons why there may be crime, let’s just bring in the cops.” That for me, that’s a problem, that’s an inherent misunderstanding of really what’s at stake and what’s going on. It goes to show that your hot take, your designer persona and whatever, none of it matters if you’re not solving real problems, if you’re not doing the research to find out what needs to be done or listening, asking.

Kendall Howse: These hot takes on Twitter or in other designer spaces, it just really tells me that you’re just responding to your own ego. You’re just responding to your own desires, your own way of life. To me, that’s the antithesis of design. For me as a designer, my two greatest tools are empathy and compassion, that’s it. Without those two things, I cannot be effective at my job, because I’m never the demographic, I’m never the person that I’m designing for, it’s always for somebody else.

Kendall Howse: If I’m not spending the time to learn what their challenges are and what their needs are, it’s moot, it’s ineffective. So on Twitter, yeah, okay, go ahead, talk all the shit that you want to talk, but who are you actually helping? Who are you serving? Because if it’s just been like, “Oh, the new Instagram logo is crap,” I couldn’t care less. It’s not an opinion with any foundation and it’s not useful, it’s not useful critique.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah. So speaking of empathy and compassion, you’re also the lead singer for a hardcore metal band.

Kendall Howse: Right, yes.

Maurice Cherry: I’d would be remissed if I didn’t mention your music [inaudible 00:10:32]. Talk to me about Mass Arrest.

Kendall Howse: Okay. Mass Arrest is my black liberation hardcore band. It’s a political punk band with a very singular message, which is really promoting the ideas of black liberation, representation and survival. Punk in general, hard core punk in particular, which is the faster, harder and more political wing of punk that started in the early 80’s, it is very often very, very, very white. I have been involved in it since I was 12 years old and I’ve been touring and playing in bands since then.

Kendall Howse: Oftentimes, I was hearing a lot of political rhetoric that was very vague. There’s a lot of say anti-police sentiment, but it’s, “Fuck the police, because they won’t let us break the law. They won’t let us like drink on the streets,” or whatever things like that. I was like, “But there’s these people over here that are actually being killed, that are being murdered, that are being incarcerated, that are being unjustly persecuted. I mean, if we’re going to talk about the police, can we talk about that rather than talking about them not letting us drink 40s on the sidewalk?”

Kendall Howse: So a lot of what I learned about community building, a lot of what I learned about do-it-yourself culture, a lot of what I learned about self-advocacy, I learned through punk. I mean, I never would have been able to travel to Europe when I was 19, had it not be touring with a band. I never would have had friends and connections all over the world, were it not for punk. I mean, really important skills came out of it. But what I was finding was what I was learning from punk wasn’t being reflected within punk, and I was still feeling very left out and underrepresented.

Kendall Howse: So there are a few kind of single topic bands, shout out to G.L.O.S.S. from Olympia, who was a trans hardcore band. The singer Sadie, she just made sure that everyone knew that this band, you’re welcome to come to the show, you’re welcome to party, but these songs are specifically for and about trans folks. I was just really inspired by what they were able to do with their band.

Kendall Howse: So, friends of mine were starting a band, who were white, friends of mine who were white, were starting a band. Asked if I could sing for it, and I was like, “Okay, but it’s going to be a black power band.” They were like, “Yeah, we know you. It’s fine. We understand that that’s what this is going to be about.”

Kendall Howse: So, I just hit a point where I realized I had a platform, where for years and years and years I was being invited into rooms to sing to people, to talk about things, and I was talking about a lot of issues that weren’t specific to my own experience. So with this band, I made a really conscious decision to make sure that when we play, what, we were in Oklahoma city a couple weeks ago, we played in Toronto, Canada, Olympia, Washington.

Kendall Howse: Oftentimes, I’m in these majority white spaces and so it’s an opportunity for me to advocate for our people to people who are interested in doing work for improvement and liberation for all people, but they just don’t have access or knowledge of, they have point of access, but they don’t have knowledge of the specific challenges that we’re facing. So, it’s just more of that work.

Maurice Cherry: Now between your design work and the facilitation work and the community work and the music, what do you think helps fuel all these ambitions that you have? Where does that drive come from?

Kendall Howse: I mean, you’re probably one of the busiest people I’ve ever known, but I bet you don’t even think of yourself as being that busy, except in frustrating moments. For me, I feel driven, I think because of the punk, I think because of growing up poor, having to create a lot of the things that I wanted. If I wanted something, I had to make it or I had to find someone who could make it or work with someone. So that, I think, has driven me to want to create. But I also realized that I’ve had a lot of help through my career and through my life, and that I wouldn’t be anywhere. I probably wouldn’t be around, were it not for that. I want to give back, I want to lift people up.

Kendall Howse: I mean, that moment where I felt so isolated to be the only black designer I knew, I don’t want anyone to feel like that. So thankfully for me, Kat Vellos had already put the work into creating the community, the least I can do is uphold and promote that community. Because honestly, I feel like if I’m not putting this time and this work into these things, then I won’t get to have them in my life, right?

Kendall Howse: It can be tough to be the only person of any targeted group, any marginalized group in a majority room, right? Well, if I can do some work to help that room understand what this person is going through or how to advocate for this person, that means that eventually, ideally, I’ll be in a room full of people that may not look like me, but can understand some of the challenges and concerns that I have, and can approach me with empathy and compassion and make my time easier.

Kendall Howse: So I guess in that sense, it’s self-serving, but also, it’s appreciation as well. They say be the change that you want to see, I’m like, “That’s so real.” Even in the most granular level, that is absolutely so real. I think that we all have influence, small or large. It was a big “Aha” moment for me when I realized that, and Mass Arrest is part of this, where I realized that I had influence, I had a platform, but I wasn’t taking ownership of it. So all of this stuff is me taking ownership of whatever influence I have and whatever platform I have, to make sure that I’m using it in a thoughtful way, that, ideally, it would benefit my life and the lives of people I touch.

Maurice Cherry: Yeah, is there a dream project or anything that you’d really love to do one day? Because I agree with you, in the sense that … I feel the same way. You have to create the experiences or create the space for yourself, especially in this society that is continually trying to marginalize and push out and press out black people in general. I mean, people of color in general, but specifically black people. It can be hard to kind of see where we in the future, let alone in the present. So, I get the sense of having to make that space.

Maurice Cherry: I mean, we’re really fortunate that technology has kind of democratized creation in a way that allows us to do that. I mean, there’s so many things I can do now, that even just 10 years ago would’ve really been, I wouldn’t say impossible, but it would’ve been a lot harder. But technology has allowed me to kind of take different pieces from here and there and make the spaces that I need for whatever it is that I’m trying to do or trying to accomplish or trying to just put out there in the world.

Kendall Howse: Yeah. So what’s the question?

Maurice Cherry: Oh, sorry. I said it, then I went on another tangent. No. Do you have a dream project that you’d love to do one day?

Kendall Howse: I have so many. I mean, really, I’m a collaborator more than I am a creator, I really love working with people. So I think of the people that I want to work with, and there are so many people right now that I really look up to. I mean, whether it be Essa Rae or whether it be Walter Hood, brilliant Berkeley architect and designer. The opportunity to collaborate with people is something that really excites me and that I’d like to do more of and let the project be just the product of that.

Kendall Howse: I think that right now we’re seeing a black Renaissance in pop culture removed from hip hop. Kind of like 90s black TV, I think we’re seeing some of that in Hollywood. So I would love the opportunity to work with some of these people that are making the things that are enriching my life. I mean, I know that … shout out to [inaudible 01:09:48]. He’s a designer, young dude, young brother from West Oakland. He’s 22 years old, he has a brand called [inaudible 01:09:56] Future.

Kendall Howse: Every time he puts something out, I buy it right away. He’s hell of young and endlessly creative, endlessly talented. If he called me up tomorrow and whatever the project, he was like, “Hey, would you work with me on this?” Like, “Yes.” That’s what I want to do, because I need to be inspired and I want to be a part of interesting things with interesting people.

Maurice Cherry: Now we’re coming up on the end of the year. We’re coming up on the end of the decade, really. When you look in the future, let’s say it’s 2025, which already seems like a long way away, but what do you see yourself working on? Where would you like to be in the future?

Kendall Howse: Well, I mean, I like where I am, I really love the team that I’m on. Getting to work on some of the most interesting and cool projects that I’ve gotten to work on professionally. So, I really hope to continue to develop my career within that space learning new tools. This is the year where I … motion graphics, really, I’m all about it. I want to learn animation, I want to learn After Effects, I want to learn 3D rendering. [inaudible 01:11:16] has been doing really interesting work around that.

Kendall Howse: Then, I don’t know, I don’t see myself in the Bay Area. It’s untenable, it’s getting too expensive. There’s just too much greed from the property owners taking too much money that they don’t deserve. I don’t know where I will be. I see myself ideally doing more advocacy work, maybe a book, and still designing and hopefully making cool stuff.

Maurice Cherry: All right, sounds good. Well, just to kind of wrap things up here, I know we’ve been going for a while now, but where can people find out more about you, about your work, about your music? Where can they find all of that online?

Kendall Howse: The best place to find all of it would be my Instagram, which is resistance.is.brutal. Then on Twitter, I’m kchowse. H-O-W-S-E.

Maurice Cherry: All right, sounds good. Well, Kendall Howse, Boo Boo, man, it has been so good to talk with you.

Kendall Howse: Always a pleasure, Maurice.

Maurice Cherry: I mean, I think just one, hearing your story about the work that you’re doing right now through Red Hat, and I can really feel the passion with your advocacy work through facilitation and things like that. But also, just this whole notion of making sure that we’re using our creative talents for good things, to put good things out there in the world. That’s something that I really walked away from this year’s kind of Black in Design Conference, really kind of feeling in my core, our creativity is going to be what saves us. Us as a people, us in the future, that’s how we’re going to survive.

Maurice Cherry: I really think that with the work that you’re doing and the spaces that you’re helping to cultivate and create and everything, that we’ll make it happen. You’re out there, through your music, giving a voice to people, you’re helping community through the Bay Area Black Designers. You’re, of course, working at Red Hat doing all this great stuff. So I’m going to really be interested to see what you’re doing in the next five years. But yeah, thank you so much for coming on the show. I appreciate it.

Kendall Howse: Thanks for having me, brother. I always enjoy spending time with you. I’m a big fan of the show, and so this is a great honor. Thank you.

Facebook Design is a proud sponsor of Revision Path. The Facebook Design community is designing for human needs at unprecedented scale. Across Facebook’s family of apps and new product platforms, multi-disciplinary teams come together to create, build and shape communication experiences in service of the essential, universal human need for connection. To learn more, please visit facebook.design.

This episode is brought to you by Abstract: design workflow management for modern design teams.

Spend less time searching for design files and tracking down feedback, and spend more time focusing on innovation and collaboration.

Like Glitch, but for designers, Abstract is your team’s version-controlled source of truth for design work. With Abstract, you can version design files, present work, request reviews, collect feedback, and give developers direct access to all specs—all from one place.

Sign your team up for a free, 30-day trial today by heading over to www.abstract.com.