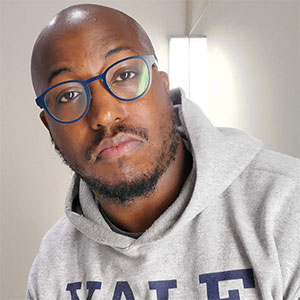

Networking is a valuable skill for designers and creatives to have, which interestingly enough is how I met this week’s guest: André Smith! His career has touched several fields — advertising, music, education — and now he runs his own firm called Appendix where he offers strategy and branding services for companies from all over the world.

We talked about his recent shift back into agency life, and he shared a bit about his day-to-day work and gave a peek into his creative process. André also spoke about his time at Morehouse, his early post-grad career, attending NYU, and his forays into art curation and being a university lecturer. André’s advice to Black creatives is simple: learn to think wider and deeper, and you’ll find many opportunities to succeed. How will you expand your horizons?

Happy Holidays from all of us here at Revision Path!

Transcript

Maurice Cherry:

All right, so tell us who you are and what you do.

André Smith:

Hey, my name is André Smith. People call me Dre. I am a strategist, an educator, and a recovering curator.

Maurice Cherry:

A recovering curator?

André Smith:

A lot of my work has to do with… I guess you could say the confluence of the fine arts, academia and advertising. And I’ve been in and out of curatorial since about 2015, but I had a bit of a pivot in about 2018 when my gallery became the classroom and my canvas became a syllabus.

Maurice Cherry:

Okay. We’ll get into that a little bit later. I was just curious you threw it out there like that. How has 2021 been going for you so far?

André Smith:

Better than 2020. 2020 was dope though, it was like a victory lap for me. If you listen to Nipsey, you know what I mean. Yeah, I went from the classroom to brand side for an e-learning platform and then agency side for agency of the year 2020, and what was considerably the hardest year for any business, particularly marketing, media and comms. That was pretty cool. And 2021’s been better still.

Maurice Cherry:

Has it been hard kind of adjusting to working from home?

André Smith:

Not per se. When I was teaching at UYC, that’s when the pandemic had hit and I began working from home doing hour and hour and 15-minute long sessions with 40-50 students. So, I got used to seeing [inaudible 00:04:28] pretty effectively. And then working from after class, which was based in San Francisco at the time when I was based in Chicago, had to perform servicing those hours. And then when I was with Martin, I was in San Francisco servicing hours on the East Coast. Like I said, better still.

Maurice Cherry:

Man, you were burning the candle at both ends, it sounds like.

André Smith:

Yeah. I have a seven-month old, Chloe. So, that plays a role too, and day by day, week by week, month by month, she’s crawling and starting to stand on her own now. Working from home… you’re adjusting on multiple clocks. Hybrid work model, the work from home model as well as the growing baby model.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Talk to me about your agency, Appendix. What’s an average day like for you?

André Smith:

Okay, yeah. I opened up Appendix… Think of it like a boat shop for go fast boats, right? For planning services and future proof strategies. I started Appendix, I want to say February. So, basically right after Martin. And a day at Appendix is waking up around 7:00 AM, watching some Bloomberg, watching some CNBC, spending about an hour on my phone, and then seeing what the algorithm feeds me depending on what platform I start with first. Start the rabbit hole of what I’m researching.

André Smith:

And then my research might lead to me thinking about someone in my network and that might lead to a text. And then that reply will lead to, “Dude. I was just thinking about you.” Or what I say to them., and they said, “That’s crazy. I just had a conversation about that in my Slack.” That’ll lead to leads, right? And getting those leads warm, especially through the network, on a Monday might lead to a conversation about a brief by a Wednesday, and that might lead to paperwork, et cetera, by a Friday. The Tuesday and Thursday are spent holding it down at home, tracking those things and getting other things in the queue.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, your work involves brand strategy, it involves culture research. And it also sounds like it involves some creative development as well. When you have a new project that comes in, what does that process look like? How do you approach it?

André Smith:

My practice area is really… at pure brand wise is really a lot to do with brand purpose, brand casting, just really a lot around inclusion and diversity, branded entertainment and social impact. And as far as brand strategy in particular, it’s really a lot to do with organic social, paid social, social commerce, and experiential.

André Smith:

Where that sits, to answer your question, is it’s a lot more to do with what is the opportunity or the brief asking of my skillset, how do I do design or strategize a vector of what’s relevant and what’s relative for that opportunity?

Maurice Cherry:

What are the best types of clients for you to work with? Because I mean, it sounds like your work really can span a number of different fields.

André Smith:

Oh, certainly. Yeah. Just most recently, I did some brand identity work for Gallery 88. That’s that’s spearheaded by Alex Delotch Davis. She’s an inaugural member of Hennessy’s Never Stop, Never Settle cohort. I do a lot of brand identity work for Kei Henderson. She used to manage 21 Savage. Now she manages Asiahn, who’s the voice of Karma on Karma’s World, on Netflix. And I’ve also most recently consulted for CSOs and CMOs at different agencies. So, working on Cricket Wireless, and Quilted Northern, for AT&T and Georgia Pacific respectively for the CSO of their AOR, likewise at Martin in that way, for Haynes UPS and Unilever’s acts.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, before you were at Appendix, you just now mentioned the Martin Agency, you mentioned Masterclass a little bit earlier. What did you kind of gain from those experiences that you still use today?

André Smith:

The CEO at Martin, Kristen Cavallo, she has a phrase, “It takes tension to get attention.” Of all the amazing gems, I picked up working across $3.5 million worth of marque accounts, that’s the phrase that always sticks out. That’s the phrase I think I draw from, my best memory from working at Martin, and learning that in numerous context, whether that was on the accounts that I was staffed on as the planning director for the social studio, or if it was more project things like AmeriSave or Happy Egg or [inaudible 00:09:14].

André Smith:

Prior to that, the most recent experience Masterclass phrase or takeaway or big thing from that. I think I heard on a Zoom, someone said, “There are different dials to diversity and knowing at least that that’s part of the energy or attitude or thinking,” at a tech company, essentially, was great for me. I think I reflected a lot of what I was most happy about with Masterclass and that [inaudible 00:09:43] feature I did back in February.

André Smith:

And prior to Masterclass, where I was consulting for their CMO, I was in the classroom at UIC. And I think a big favorite quote of mine experience that can be put into a quote or alchemized into a quote is, “Google, and then go outside.” My friend, Andy Deza, said that when he came to guest lecture for me amongst a host of other awesome guest lecturers, like Joe Fresh Goods, Ferris Bueller, Sam Kirk, Midori McSwain, who’s now the AD of a brand strategy at Spotify. But that was, I think, my most favor quote, because that was something that the students would say back to me over the semester and the students who would then take me for other classes.

André Smith:

When I was at UIC, I taught consumer behavior, global marketing and advertising and sales. But the students who started with me in taking me for consumer behavior, who took me for global marketing and ad sales, that’s a phrase that they would impart back to me. So, it was nice to see the ripples in the pond, I guess.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. It’s interesting; sometimes with those past experiences you have to be out of them to really learn or know what you’ve learned from them. Because when you’re in it, it’s a bit of a different

André Smith:

Couldn’t agree more.

Maurice Cherry:

Let’s switch gears here a little bit. We’ve learned a bit about kind of the work you’re doing now, but let’s hear more about your origin story. Tell me where you grew up.

André Smith:

I think of myself as a global citizen, but at the end of the day, I’m still just a kid from the North Bronx. I grew up just shy of Gun Hill Road on Burke Avenue in, I guess what used to be very Italian and Jewish [inaudible 00:11:32], ’86 is my year. By the time I was on the scene, right, I came to life, it was predominantly Caribbean. And to this day it still is very much Jamaican, Trinidadian, Guyanese families that historically have occupied these homes. Generationally have occupied these homes.

André Smith:

And my origins, I guess, besides being kid who grew up in the Bronx and still frequently go back, even just to sit in a car in front of the house I grew up in, just to keep that connection, I guess. My origins that I grew up in the Bronx is… Well, a lot of people don’t know maybe about me because they see me in art galleries or they see me in advertising or they see me in the classroom is I started in music.

André Smith:

My mom’s younger brother is a successful music director and bassist. He went to [inaudible 00:12:23] purchase with Amanda Seals, Amanda Diva, Tiffany from Insecure. And short story about him, he had the opportunity to tour with Lauryn Hill and the Fugees’ global thing. It was going to be his first day; it was going to be in Japan, but it was between going on tour with the Fugees and going to college. And my mom was like, “If you get your teaching license and you get your degree, you can tour with anyone and you can also have the backup plan of having other options.”

André Smith:

He was torn about it, but decided to go to school and pass on the opportunity. At the same time, my dad’s older brother had a recording studio in his basement and he would have local acts who end appearing on the halftime show on NYU or City Hall Radio. He worked with [inaudible 00:13:11] or artists like that. And I guess between seeing my mom’s younger brother’s conflicts between the bright lights and the steady road, and my dad’s older brother’s approach of having a steady road, but also having an entrepreneurial spirit because he split the basement with my aunt who had a hair salon. So, the basement of that house was basically all business, right? It was like cash and carry operation.

André Smith:

That had a very big impression on me, I think. Understanding how to keep a main line, but also keep your eyes open for other bigger opportunities. And then talking about looking for bigger opportunities., I was always a ferocious free, even if I didn’t like class and I loved reading XXL, and The Source and Bonsu Thompson, Jason Rodriguez, whether or not… I’m calling them as friends.

André Smith:

But reading their words in those magazines about the artist that I was starstruck by, that played a very big role in my understanding of the music business. So, when I had the opportunity to meet Joaquin Waah Dean, one of the co-founders of Rough Riders, of all places at a Cheesecake Factory. I can’t say I needed the right thing to say, but I think my passion and my sense of understanding was evident to him.

André Smith:

So, short story, I ended up interning on Jadakiss’ sophomore album, Kiss of Death. And that had me working out of Worldwide Plaza. And if you know music, that’s the headquarters for Def Jam and the labels that they distribute for [inaudible 00:14:50]. And I spent my senior year of high school interning on Kiss of Death, and I spent the summer before college going to Morehouse and turning on [inaudible 00:14:57] Purple Haze. I didn’t have a favorite in the verses bible between The Lox and the Dip Set until Jadakiss said, “Cam lives in Miami.”

Maurice Cherry:

It sounds like early on you kind of were more geared towards music because of the exposures from your uncles to recording artists, to recording studio, but you got to Morehouse, you didn’t study music. What’d you study at Morehouse?

André Smith:

At Morehouse, I went into study political science and Keith Hollandsworth told me, “That’s not for you.” And then I heard about Phillip Johnson and then I realized, “Maybe not.” And I thought it was going to be business marketing, but me and business policy weren’t going to get along.

André Smith:

But then after interning at Bloomberg in my sophomore year, I came to realize that my real skillset and my strong suit was really more in comms. And I realized that the sharp edge of the Sabre for me would be English through degree, right? And focusing comms as my way into marketing.

André Smith:

But the road doing music… And the other thing that I really loved about my time as an A&R intern for Alimah Shamsid-Dean, who ironically up would later go on to work at Translation with Steve Stoute. What I loved about the work I was doing, or the work I was learning, coming to understand was where all the dots connected, right? Fast forward, leader strategy. But also, my eye, my ear for product placement, it was always mentioned in bars and raps, but then you also go on to see it in music videos.

André Smith:

And I was wondering, “How’d that get there?” Being a Jamaica kid from the Bronx, when my mom [inaudible 00:16:36] spent time with my granddad, I would always end up in the box with all the James Bond movies, 007. And it was always just like the best product placement. Whether it was the Aston Martin or it was the Omega, or it was the Bright Lane, or it was the BMW, or it was even Avis, talking about cars. But I was always groomed or cured to see where things connect and where brands fit.

Maurice Cherry:

Interesting.

André Smith:

And going into college in Atlanta at that time, 2004, Vote or Die was the brand on campus. Morehouse’s the brand and Spellman is the brand. Not just because they’re the brand and [inaudible 00:17:15], but nostalgically, they’re the brand because you see them in Boys in the Hood. You see them on the Fresh Prince. You see them referenced on a different world. You might see it pop up in Living Single.

André Smith:

For me, I distinctly remember in my senior year, I was deciding which school to go to, and I graduate high school with honors, so I had options, but I chose Morehouse for… I think influenced by two big scenes. I’ll never forget there was a couple scenes or episodes of Making the Band where Puffy, who’s ironically from my hometown… I moved from the Bronx, I moved to Mount Vernon, and Mount Vernon’s the hometown of a couple of legacy individuals, most notably DMX Rest in Peace, but also Sean Holmes and Denzel Washington, whose son, John David, went to Morehouse and Denzel’s house [inaudible 00:18:03] from Morehouse.

André Smith:

But seeing Puff in that Morehouse Letterman just always like put something in my head. And I know he went to Howard, I know he didn’t finish Howard, but seeing him wear that, it just puts something in my head. And then there was this one scene in the real world, San Francisco, ironically, as I live here, on the West Coast and the Bay primarily, there was this one scene with [Jaquis 00:18:25] where he was confronted with an instance of racism, and the way he handled it. And then he went to Morehouse and seeing him in the Morehouse shirt, that just left a real big impression on me also.

André Smith:

For those reasons, and as well as the school’s legacy and Benny Mays and Dr. King and Spike and all these amazing people, those are really big reasons why I think I chose Morehouse and going to Morehouse. And doing the internships I did at Bloomberg from sophomore year to senior year, I came to just realized that comms was really my gift, strategy and connecting the dots authentically and organically for brands is another gift that I have. And I’m not going to probably have the best shot doing and delivering against that if I go the traditional road of getting a business management degree or a political science degree.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Because those degrees are pretty common at Morehouse. I just remember, even from the years that I was there, right outside of Wheeler Hall, everyone’s out there in their suits, political science folks, the business folks, I was a math major. We just walked right past them.

Maurice Cherry:

I know what you mean though. I mean, Morehouse itself, outside of all the names and stuff that you mentioned just sort of has this draw for a lot of people, but it’s so interesting because in a way it sort of depends what you end up going into kind of either during school or after school. Because I started going into design right after school, and even working at places in Atlanta where I was not the only Black person. I was surprised how many people had never heard of Morehouse. Didn’t know what it was, didn’t know where it was.

Maurice Cherry:

I’m like, “It’s here in Atlanta.” I remember my first day at AT&T when I had told some of people on my team I was at Morehouse and they were like, “Oh, where’s that?” And I was like, “Well, if you look out the window, you see that green roof way off in the distance? That’s Morehouse.” And they’re like, “Oh, I didn’t know Atlanta went down that far.” I’m like, “Give me a break. Come on.”

Maurice Cherry:

I mean, you had these opportunities for doing these internships. What was your kind of early career after you graduated? What I’m hearing is that you probably had something lined up once you graduated for Morehouse.

André Smith:

Yeah. I could have stayed at Bloomberg and did the A desk, analytics desk thing, but going from A&R to comms, and then looking at analytics just didn’t feel like the best fit. And to my parents, it looked foolish at the time, but I had a vision for the bigger idea.

André Smith:

I ended up, honestly, working for free in Tribeca for Damon Dash and Coodie & Chike. Chike Ozah and Clarence Coodie Simmons, creative control TV and DD172. And I think for free, because it was an apprenticeship in every sense, in the sense that you really have to get in there for yourself. But also the things, you were learning from real masters of their craft. Kanye on [inaudible 00:21:32] was just talking about the degree of reverence and respect he has for Damon, despite whatever issues or bad blood, Jay Z would’ve been remiss if he did not acknowledge Damon in his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speech.

André Smith:

So, having the opportunity to be a strategy apprentice to Coodie & Chike, and work on product placement for brands like Pepsi, Adidas, Heineken, Porsche was really, really a great opportunity for me. And it brought future forward that early eye and appetite I had for connecting dots authentically and organically with brands, from when I was a kid watching these 007 movies. And then, from working on Purple Hayes, my summer before college, and then getting a chance to kind of learn from the master, so to speak.

André Smith:

After college was really great to me. In my time at Bloomberg, I worked across ad sales for print, one of their print titles called Markets Magazine. I worked across key accounts at the time when the subprime mortgage crisis hit, I was actually staffed on Bear Stearns. So, talk about learning trial by fire. And then in my last summer I worked event planning for key territories, North America.

André Smith:

And that Bloomberg is stacked in a way of its radio TV and print and, and terminal. And similarly, as I learned in my time working in Tribeca there, they had the gallery, they had the mezzanine for creative control TV, but they also had executive suites and offices and filming space. And they had an event performance space downstairs, as well as the recording studio that was manned by Ski Beatz, the producer who did the bulk of Jay-Z’s Reasonable Doubt. And I looked at them as two sides of a coin, almost. As parallel learning opportunities.

André Smith:

One was a big global enterprise by a billionaire, even though he was the mayor at the time. And the other was a factory led by the idea engine that birthed two billionaires, speaking about Jay Z and Kanye West. Granted they weren’t billionaires at the time, but it was evident with the way that, from what I learned of Damon’s process, it was a great compliment to what I had learned at Morehouse. Ironically, working on Heineken at DD172 Creative Control led to me working on Heineken at Team Epiphany, an agency owned by a Morehouse alumni, Coltrane Curtis.

Maurice Cherry:

So, during that time, when you’re kind of working as a strategy apprentice, and as you say you were doing it for free, how were you feeling during that time? What was going through your mind during that time?

André Smith:

At the time, I initially loved peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. And by the time I was done with that, I hated the idea of paste anything. Justin’s peanut butter otherwise, I was over it. But at that time, DIY, do it yourself, was a new phrase and new concept. Social was still very fresh. And when I wasn’t in Tribeca, I was spending the rest of my time in the Lower East Side at the Alife Rivington Club Courtyard or at Reed Space, found by Jeff Stable, or at Prohibit, which was helmed by Chace Infinite, who later went on to become the manager for ASAP Mob and Griselda.

André Smith:

At the time, I was just always in the mode to learn. I knew there were things I learned on campus and in school. One thing I didn’t mention in my time in Atlanta is for a while, I was an apprentice to Clay Evans, who is the road manager for a lot of successful southern hip hop artists, but notably TI and Travis Scott.

André Smith:

One of the things I really appreciated while running with Clay was there’s a lot of things that you don’t learn in the classroom. There’s a lot of on-the-job learning and understanding and expertise that you have to observe in the moment to get good at the job. It’s like being a page at NBC or something.

André Smith:

I spent a lot of my time, when I wasn’t on campus, I was up in Castlebury Hill at Slice or over at City of Inc with Tuki and Maya. Tuki Carter and Maya Bailey. And at the time, like I said, I was just always in the mood to learn. And what I was thinking and feeling at that is there’s a lot of opportunity for influencers. And later on, obviously that became really true.

André Smith:

But at the time it was just seeing things in motion. Your online presence didn’t matter. People really had to know you outside. If you weren’t getting inside, you weren’t going to make it, unless you knew the right thing to say or you came with the right people. I saw a change coming, but I also just really appreciated the time and the moment when people really had to know each other.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. I know those kind of times where, especially once you first start to get out there and you’re not going right into a particular job, there’s so much networking that you have to do. Let’s see. You say you went to Morehouse in ’04, so this was around ’08, ’09 when you were doing a lot of this?

André Smith:

Correct.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. I remember being in the city during that time. It was a really sort of buzzy time, particularly if you were doing things around design or tech or something like that. It was just a lot of energy and activity going on in the city. You could go down to Octane and end up meeting up with folks or you’d go to some… meet up in some other event or something like that. Of course, now with the pandemic, a lot of that-

André Smith:

That was a phrase. A meetup. The meetup. Event Bright. Event Bright was it. Early QR codes.

Maurice Cherry:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

André Smith:

Yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. there was a lot of that during that time. And I mean, of course now with the pandemic, it’s not the same, but you certainly had… Oh God, I remember that so vividly, because that was right around the time I was at AT&T and I quit my job and then started my studio. And so I just had free days all the time because I had some clients, but you go, you talk to other creatives, you see what other work you can get into, see what other projects you can fall into. Something like that. Atlanta sort of facilitated that type of creative spark, in a way, to go out to these places and meet people and do things. I mean, in hindsight, it was so easy.

André Smith:

Well, it looked easy. Dave Chappelle talks about expensive experience. I do it in five minutes because you’re paying me for the five, seven years it took me to learn how to do it in five minutes. You’re paying me for the time I did it. You’re paying me for the time I prepped to get it done, at the level as projected and as expected.

André Smith:

But to the tune of Atlanta and training, Jedi-level training, home coming in itself, but then also Market Friday, Wednesday on the Yard, the City, Rocky Road over there by Piedmont Park, Little Five Points. I was just talking to a client the other day and working on some brand identity work and she was referencing her time in the early shaping of Wish, and how it’s now basically a cultural institution [crosstalk 00:28:49].

André Smith:

The whole thing about it is even Little Five Points, you have to move carefully. You don’t know what [inaudible 00:28:56] or what guy would FaceTime… You don’t know who’s who. So, act accordingly. And this is Atlanta in ’04, ’09, 2011, 2013. I can talk about Atlanta today.

Maurice Cherry:

It’s a totally different… I mean, you’ve been to Atlanta recently. It’s a totally different vibe over there now because largely because of gentrification.

André Smith:

Gentrification and decriminalization, I think, and the dual pandemics have certainly played a role in how leadership and community have to respond and adjust for sure.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. That’s true.

André Smith:

It’s also a gold rush at the same time right now. If you’re up, you’re up.

Maurice Cherry:

That’s true. Yeah. You’ve worked at quite a few agencies. You mentioned Team Epiphany, you’ve also been at IPG, you’ve been at Momentum. When you look back at those agency experiences, what do you think was the most impactful based on where and what you do now?

André Smith:

I guess just going off of networking and best… [inaudible 00:30:00] muscle memory, trade craft, right? Where that’s learned, how that’s shaped steel on steel, and how it’s optimized and where that’s applied or deployed. You mentioned Momentum. I’ve done three tours with IPG. Momentum media brands, I consulted for a while with Octagon and Adidas. I just got a text from a Morehouse bro who is now at Adidas covering Atlanta, NY, and ATL and wanted to talk about some ideas. So, look at God, right?

André Smith:

I guess I’ll talk about Momentum first, since I spoke about Martin. I can talk about Momentum second to that. Media brands, I think that the biggest memory or experience I had with Media Brands was hosting the Super Bowl USA Today Ad Meter Watch Party in New Orleans. That was heavy just because it was post Team Epiphany, post doing some post grad studies at Rutgers Center for Management and Development, the CMD, and being in a room with the CMO of Subway, Susan Creedle, to name a few people. Serious stakes.

André Smith:

And I really credit the Five Wells from Morehouse and so on and so forth with kind of giving me that training and that base practice to know how to move in that room. Talking about moving in rooms, talking about global, my favorite memory, I guess, or learned experience from Momentum is shortly after I had left momentum. I took my first leadership director role as strategy chief at 1stAveMachine, which is actually a production company, not even the ad agency.

André Smith:

But part of my deal with 1stAve is I went with two other partners to come for the Creative Lions. And I bumped into the CEO of Momentum, Chris Weil, on La Croisette. And watching his head spin. I said, “Hi, Chris.” Because he’s used to see me in New Orleans. “What you’re doing here?” And I gave him my answer, but walking down the rest of La Croisette on the way back to Palais des Festival, I was thinking like, “Yeah, what am I doing here?”

André Smith:

You’re hanging with [inaudible 00:32:04], having rose on a pier. And you’re all of, what, 25, 27? It’s dope to even be able to have memories like that. So, when I stay in touch with people, like Bonnie today, whether it’s about anything, I have that memory and that connection or… I don’t know what you call it, what do they call it? A sign of early promise or whatever? As a reference.

André Smith:

So, that’s Momentum, that’s Media Brands, Martin. Yeah, just being there with them for agency of the year at the part where it’s really gridlock in the mud, like any given Sunday, rainy day stuff, answering briefs, when the world’s upside down, it isn’t an easy job. I’ll just leave it there on that. And learning from their leadership, Elizabeth Paul, and the leaders who I report to it’s just a really great experience.

André Smith:

To switch, I think I spoke a bit about the classroom, “Google and then go outside,” knowing that they remembered at through three classes and that some success stories. I have a couple students who… Some of my Padawans who learn some of my Jedi ways, I guess, but they’ve gone on to do well for themselves. And one of them is associate project manager at Fluent 360, AAPR at Nissan. Another student is an account executive for Whirlpool, for corporate orders.

André Smith:

Two of them decided to start their own shop, hopefully gets absorbed by a bigger shop one day because I know they have chops to do it. And I guess before that, in my curatorial space, working as a curator and commissioning private commissions and sales, I would say biggest memory from that… I’d say like the opening day of my first show was… I’m literally doing everything. I’m getting food delivered, buying a case of wine and getting champagne.

André Smith:

And that same day, a review came out written by Antwaun Sargent, who’s now the director of Gagosian Worldwide. And at the time he wrote the review, he wrote it for Vice. And that came out in the afternoon, and before the show closed, I sold my first piece and it was a four-figure photo essay. That was hard to top. But then I topped it by doing a three-month… That No Window Shopping residency ran for five months in Williamsburg. And that was followed by a three-month residency in The Mission in San Francisco later that year.

André Smith:

And the only reason why I didn’t do Brexit… The only reason why I didn’t do No Window Shopping UK was because of Brexit had just hit at the time. But yeah, those I think are my big memories and takeaways, outside of my time in music. And I guess knowing that I worked on Jadakiss’s Sophomore album that hit Billboard when it debuted, and I worked on Curren$y’s Pilot Talk, and I was at DD172. And that made a big debut when it hit Billboard. Those are my memories from those times. And I guess all the rest of them are a blur, lots of late nights.

Maurice Cherry:

You’ve been achieving all the success. After you graduated, you really kind of like made your own way, starting out doing this kind of free apprenticeship thing, and then working with agencies. You produced this No Window Shopping event. And then during this time, you ended up going to grad school. What spurred that decision?

André Smith:

Yeah. I graduated Magna Cumme Laude NYU Tisch with my Master’s in art and public policy, and connecting all of the dots from going to Morehouse and… I’d be remiss if I didn’t credit this.

André Smith:

A big impression on me from my time at Bloomberg was Bloomberg Philanthropies. And I think it kind of groomed my eye to the power and duty of big global interests and those types of firms when it comes to corporate social responsibility, which I guess we now call social impact, for all intents and purposes.

André Smith:

And with my work with social clubs, like Noya House or Soho House, or even co-working spaces like The Yard, [inaudible 00:36:02]. I was always very intent on being accountable for the diversity in the room and the diversity I brought to the room. And in time, being around the four A’s, and ADCOLOR and those types of organizations and initiatives, I just come to see inclusion, diversity and equity and social impact really more married than they’re recognized for.

André Smith:

And a big part of what drew my attention to the art and public policy program is I saw it as a way to bring forward my passion for the arts through music and my experience, and my, I guess, you could say success as a curator. And the way I see the relationship of art, community and artists, whether you call them influencers or otherwise, how that relates to brand. When you look at it, even if you go to the Whitman or the Underground Museum or the Studio Museum in Harlem or the High Museum in Atlanta or [inaudible 00:37:07], whichever institution you want to patron, you’re going to see it’s sponsored by these big brands.

André Smith:

So, I was really interested in that initially, but the real reason why I ended up going to do the program is I found, as I was getting more press in Vice or Hyperallergic or so forth, some of the questions I was being approached with by the writers, and maybe sometimes even the questions I was being approached with by collectors or representatives of institutions I’d meet, who came to my openings, who came to the events that I put together as part of the culture programming to stem my shows or my exhibitions and my group exhibitions from opening to closing, I will be honest.

André Smith:

I don’t like the phrase, “I don’t know.” Coming out of Morehouse, it’s not a phrase you hear very frequently on the yard. And if you do hear, it’s met with raised eyebrows, “What do you mean you don’t know?” Either you’re not invested or you’re not trying. But being approached with questions that I didn’t have ready-aimed fire answers for wasn’t something I was used to, happy about or comfortable with.

André Smith:

When you don’t know, that means you need more knowledge. It just worked out that my academic advisor was the artist Karen Elizabeth Finley in my time at Tisch, and I had the privilege and opportunity to do electives at NYU Stern, NYU Steinhardt. And in that time, I was a teaching assistant to Rosalie Goldberg, the founder of the Performa Biennial and Director Emeritus of The Kitchen, which is like a legacy institution in Chelsea for anyone who knows about the arts from the ’60s and the ’70s and the ’80s.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, you’ve mentioned earlier about… excuse me, about being a lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago. How did that opportunity come about?

André Smith:

Yeah, that is serendipity. And luck is really just preparation, patience and timing. And you could just boil it down to that because at the time I just finished my Master’s and I had envisioned or fancied myself going to a firm like LaPlaca Cohen because that would be a beautiful marriage of the things that I had done and the interest I’d cultivated and cured to that point with my Master’s program.

André Smith:

In the time I was at Tisch doing my Master’s, I did my graduate field work with Twitter and Creative Time. It didn’t take. And then 45 crushed the endowments for the arts and the humanities with one pen stroke. So, the funding for the things I wanted to do, the pool got a lot smaller. It was going to be limited to fellowships and things like that.

André Smith:

And my wife, Nicole, decided that she wanted to pursue her Master’s degree. So, she got into the 2Y program at Northwestern Kellogg and spent a lot of time in Chicago looking to maybe explore and expand my curatorial practice in that city. It was slow motion on that, and it just happened one day I was at a restaurant and some individual, the lovely lady that sat next to me, this was all pre-pandemic, no face mask required. We started up a conversation and she was sharing about her daughter and her daughter going to Notre Dame and looking to do business and looking for internship opportunities, and I, empathetically, generously offered to say, “Well, if she has any interest in Bloomberg, if she’s trying to start her way in through media, I’d be more than happy to make an introduction. I actually know one or two more house alums who were still there. It wouldn’t be a problem.”

André Smith:

And she gave me her card and we got in touch and I was looking for opportunities maybe with the school. And when she looked up my LinkedIn and she kept me back, she just said, “We should talk.” I was like, “Yeah. I looked at some opportunities on the site. I’d like to talk about.” She’s like, “No, you should teach.” And I was like, “Okay.” I joined the faculty as an adjunct lecturer. Within a semester, I was promoted to visiting a lecturer of culture and innovation in the managerial studies program, the college of business administration at UIC.

Maurice Cherry:

When you look back at that time, what did your students teach you?

André Smith:

Oh, wow. A lot of my students were first gen college attendees. A fair number of them were new immigrants, ESL. They taught me a lot about patience and empathy, but they also taught me, I would say… My pedagogy at UIC was really cured around critical thinking, immersive play, team dynamics and group work. And what they taught me is that this generation needs a lot more help training, coaching, and practice in group work. A lot of, “I, I” focus: iPhone, iWatch, Instagram.

André Smith:

And a lot of the appetite for instant gratification, I think, makes it hard to develop the patience and empathy to be a good team player. That’s why in my two-year tenure at UIC, I passed on midterms and finals, and I ran my classes like agencies. 14-week sprints. And ironically, that was really good practice and training for me, doing sprints for Masterclass and then Martin.

André Smith:

But in the way I ran the classes, or the agency as class, it was to do with your four… Teams are broke up in fours, right? Account, media, creative and art direction. And giving them those, I guess, buckets to play in, seeing how they use that to acquiesce to… Using immersive play to acquiesce to better group work by making it immersive was very insightful for me. And I was not shy about using and applying that to the juniors I managed as a planning director at Martin.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, let’s say someone out here is listening to this and they’re picking up all the names you mentioned and all the different opportunities and things that you’ve done. If somebody out there wants to sort of follow in your footsteps, what advice would you give them?

André Smith:

Besides Google and go outside? I would say, know your power. Leonard [inaudible 00:43:27], he has a show on Comedy Central. He has a book out about knowing how to apply and leverage… The word he uses is privilege. But I feel like that’s a bit cagey. We want to be careful with the teeth on this.

André Smith:

But knowing how to learn and leverage your superpowers is really important. I wear glasses, right? I’m a New York kid. I talk fast. There are times I’m in the room where I’m overdressed, there are times I’m in the room coming from another series of a couple of events or meetings where I’m client facing to that audience and I might find myself underdressed, which isn’t really true because I’m always confident about it. I wore a Yankee cap into City Hall, which I’ve actually done before. So, there’s that.

André Smith:

But I’ll use my Yankee cap as a springboard because it’s me being true to myself. I’m from the Bronx, I’m proud to say it. I’m from the same place as Ralph Lipchitz and Calvin Klein, [inaudible 00:44:18]. So, I’ve always been keen to know and not be shy about what my superpowers are. At the same time, I would caution and advise, be mindful of other people’s superpowers and their sensitivities.

André Smith:

But make one of your superpowers curving sensitivities and amping room for empathy and collaboration. One of the big takeaways I also remember from my time at Momentum was the idea of… Really, the philosophy and the practice of co-creation. Answer the brief with the client. Don’t just answer the brief for the client. And likewise in relationships, whether they’re emerging or continuing, be the friend that’s like the therapist, not the friend that’s the friend that people need to see a therapist about.

Maurice Cherry:

Where do you think your life would’ve gone if you weren’t doing what you do now?

André Smith:

That’s a really good question. When I was a little boy, I thought I wanted to be a judge. And as I got older, volume two on cassette, I saw myself working in management because I really have a passion for the artists. Evident to any artist who I ever paid a studio visit to, who I ever featured in the show, or even if they weren’t in the show, I featured them in some culture programming I was doing for a social club or a client.

André Smith:

It’s not so much more about like the power trip with judges and lawyers, but about having the power to defend and to represent, for people who might not be best equipped to represent themself or their value. But I think working as a creative, whether that’s a creative strategist or curator or a creative producer, in a lot of ways, you have almost more responsibility and power than a judge because while a judge can set precedent as a creative, you can inform or almost even at sometimes, dictate culture.

André Smith:

And ultimately, culture is the law of the land and it rules the day. It almost rides higher than the law in a lot of cases, which is one of the things that leads to us redrafting and reshaping culture. So, what I just said is basically what I learned in my Master’s program, art and public policy because there’s culture lowercase C and there’s culture capital C. And then their culture is lowercase C. But culture informs public policy and public policy ultimately informs legislative and written policy.

Maurice Cherry:

What do you want your legacy to be? When you look back at your career, you look back at what you’ve accomplished to where you are now, what do you want to do in the next few years or so, something like that?

André Smith:

In the next few years, my big bet is automated retail. And I have a smart answer for that. More coming soon. But I guess when it’s all said and done, a lot of people will laugh and libate to my memory and say, “He sometimes had a long voiceover. And sometimes it was a lot to follow, but it all came with a lot of passion. And if you’re listening, you understand. And even if you don’t understand, he always cared enough to break it down. He was the type of guy who would sit with you for an hour, helping you with a problem. When you asked him for $5 and he was like, ‘You don’t need my $5. I just gave you $5 million worth of insight and energy.'”

André Smith:

And it wouldn’t be bad, I guess, if people say, “He loved hard and he played hard.” Because I think for me ultimately that’s what it comes down to. Frustration is just fun with a lot of filling letters in the middle. And I’ve always, probably why, I guess, I chose English and leadership studies at Morehouse instead of business, marketing or political science is because in those more constrictive spaces, it’s hard to start the tape with, “Let’s cut down frustration. Let’s just get to the fun.”

André Smith:

What does that mean? How does that work? What are you talking about? I’m talking about the answer to the brief, I’m talking about the way to start today’s lecture. I’m talking about a way to get over worrying about the glass breaking on the shadow box and the show starts in a few minutes. Let’s go Banksy with it. Let’s put it through a paper shredder. Let’s see what happens.

Maurice Cherry:

Well, just to wrap things up here, where can our audience find out more about you and about your work and everything online?

André Smith:

Dre Powers. D-R-E P-O-W-E-R-S. Dre Powers. Everything’s basically Dre Powers. You can find me on that, and you can see some of my legacy work and some of my latest work on AppendixWorks.com, A-P-P-E-N-D-I-X W-O-R-K-S.com.

Maurice Cherry:

Sounds good. Well, André Smith, I want to thank you first so much for coming on the show. One, just for sharing your expansive career and the work that you’ve done. But I think also it’s good, certainly for people in our audience to hear, like you mentioned, sort of the passion behind the work that you do. Clearly you have a love for this. You have a knack for it. You have an affinity for it. And I’m glad that you were able to really share that with our audience through this interview today. So, thank you so much for coming on the show. I appreciate it.

André Smith:

Thank you for the space and the time.

Sponsored by Brevity & Wit

Brevity & Wit is a strategy and design firm committed to designing a more inclusive and equitable world.

We accomplish this through graphic design, presentations and workshops around I-D-E-A: inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility.

If you’re curious to learn how to combine a passion for I-D-E-A with design, check us out at brevityandwit.com.

Brevity & Wit — creative excellence without the grind.

The presenting sponsor for this week’s episode is

The presenting sponsor for this week’s episode is