In the early 1990s, a number of Black design professionals came together to create the Organization of Black Designers (OBD). It was intended to be a counter to AIGA—to create a design community specifically for and by Black professionals in the fields of graphic design, interior design, architecture, urban planning, fashion design, advertising, transportation design, and product design.

At one point, OBD claimed to have membership in the thousands, but OBD today seems like a shell of its former self. According to it’s official Wikipedia page, OBD has 8,700 members; 3,500 hundred of those being professional designers. One tweet from their official Twitter account even claims it reaches 25,000 members. But even still there is little recent activity on their official site. Their most recent blog post is from 2016.

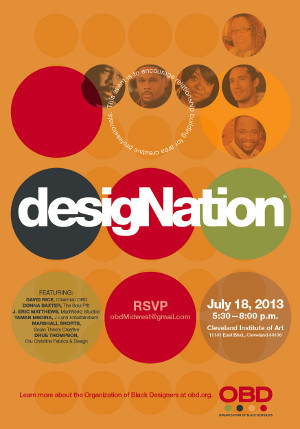

I first learned of the organization in 2004 as a college student when I attended my first and only portfolio review and networking event called DesigNation. I came away from the event with mixed feelings. On one hand, I met my longtime mentor Lorenzo Wilkins. But on the other hand, DesigNation provided the worst professional advice I had ever heard. During an opening panel discussion, a Black design professional told a room full of hopeful young talent that nothing is beneath them. I ignored that advice, and fourteen years later my career is better because of it. Despite all that, I still root for OBD.

Ever since then, I wanted to learn more about the organization. Who were its founders? How were events planned both then and now? Who did the branding? And unlike its contemporary peer AIGA, why does the Organization of Black Designers often seem lost to history?

In my research for this piece I quickly discovered that there would be no way of telling a singular definitive story of this mysteriously opaque organization. I talked to OBD staff and members past and present, and through multiple perspectives, I found out about OBD’s early days, memories about its influence and internal struggles, and tried to figure out where OBD can go from here.

[Disclosure: David Rice, the founder of OBD, was unavailable to interview at the time this was published.]

Part I: “The funny thing is it started with just a meeting.”

Leon Lawrence III, former vice-president: The Organization of Black Designers was a design organization that brought together different design disciplines: architecture, interior design, industrial design, graphic design, and multimedia design to have a…I guess you could say an exchange of ideas. The organization was started by David Rice and Shauna Stallworth and they had this vision of bringing African-American designers from the different disciplines together and to have an exchange of ideas. Get a sense of who’s out there in the industry, and working. And what can we get from feeding off of each other.1

Shauna Stallworth, former executive director: The birth of the first multi-discipline design organization triggered a tsunami in the design industries. Publications were calling for designer references; stories were written on the cross-pollination between graphic design, interior design, industrial design, architecture, and fashion design. There was instant traction on the need to see more designers of color in all aspects of design. Design publications, international organizations, design firms and professionals immediately responded to the call to “arms” to increase the visibility hiring and empowerment of designers of color.

Lorenzo Wilkins, former member and brand identity designer for OBD: Around 1991, my sister sent me a Washington Post Magazine article of an interview with David Rice while I was still living and working in Los Angeles. I was impressed. David Rice and Shauna Stallworth had conceived OBD and it was beginning its maiden voyage when I moved back to the DC area around that time. I contacted David and Shauna and we hit [it] off right away. I was impressed that finally there was an organization that was influential enough to change the narrative about the ability and validity of designers of color in all disciplines.

Lawrence III: Someone came up with the idea, “Why don’t we start chapters?” Why don’t we do this on a small scale, and each of the major cities on a monthly basis or yearly basis [can have] these small chapters of different design disciplines of people of color. When we left Chicago, we had to come up with an idea to start the Organization of Black Designers as a group with about four or five chapters dispersed across the country. One of the chapters was of course in Washington, D.C. where I reside. We got together and had a meeting and talked via speakerphone with David and Shauna. [We] came up with bylaws and started the Organization of Black Designers. David had written up a bunch of things that he wanted to use as a springboard to push our organization in a certain direction. Everyone grabbed that directive and ran with it.2

Source: Angelfire

Wilkins: I joined soon after and worked with OBD on a variety of design projects including their identity program. It was a while ago but I remember the request to develop an identity that reflected the philosophy of diversity and inclusion that the organization was all about.

I had to think long and hard as to what that might look like. I did not want to travel down the road of cliches. Simplicity was the key for me. I wanted to do something I had not see before when it came to portraying diversity. The name was long so the initials “OBD” appeared to be very important in establishing their identity in a clear, simple fashion. I went with a typographic solution but I also wanted to create a mark to accompany the typeface. So I worked up a very simple system of four dots of various colors to go with the logotype.

Andrew Bass, former member: I first got wind of OBD back in 1996, I believe. It was a promo or ad I saw for [the] DesignNation conference held in Philadelphia. It grabbed my attention because it was the first time I had ever seen a design conference focused solely on designers of color. I was only a few years out from college and was hungry for information about black designers.

It was pretty impressive and had some big names speaking like Jo Muse of Muse, Cordero and Chen and Cynthia Jones of Jones Worley. I was just awestruck by the large crowd, the stand-out collateral/signage and seeing so many faces like mine. It was my very first design conference. To be honest, I was a bit worried [of] what I was going to be walking into because of how some folks in our community try to pass off events as professional when they really are just shit shows feeding that stereotypical image of us not being top-notch. It made me feel proud to attend for three days—if I remember correctly—and everything went [smoothly]. The sessions were informative, the evening activities were fun, and it left me with so much inspiration when it was over.

Jacinda Walker, former midwest coordinator for OBD: I first learned of [OBD] I’d say about 2000…maybe 2004. Because they were doing conferences in the early years, as they called ‘em. They were doing conferences every year, but maybe in like the last ten years, they started doing them every other year. I heard about OBD and I knew I had to be wherever they were. Wherever there were other Black designers. And understand that many of the people I’m talking to you about as far as those who mentored me, they were not Black designers. So I never had a Black design mentor. When I heard of OBD, the first thing I thought was, “Oh my gosh, I hope I meet somebody here” My whole mind opened up. And so I called [OBD] for a long, long, long, long time. And I aggressively pursued a dialogue. And I finally got in contact with David Rice. He has spent his life working for the cause of Black designers.3

Lawrence III: We really took on the idea of helping the Black design community. Young designers, young college students coming out of school trying to get into the industry. We had come up with this group of seminars called “Reality Check” in the Washington [DC] area. I would bring a bunch of professionals from all up and down the eastern seaboard;designers — not necessarily all of color — who had a discipline that they were comfortable teaching in. College students would come in, and talk to these professionals, and ask questions. They would ask everything—anything from how much you can expect to make the first year, to “how should I dress for my first interview,” to “what is the best way to communicate and get my portfolio seen.” I guess we ended up having about 6 or 7 seminars where you could switch classes and have breakout sessions where students could show their portfolios to a professional. And it was wonderful. It was highly educational. It was motivating and inspiring for the professionals to meet with young people and see what the new direction of the industry was. College students have their own things to offer. They’re on the cutting edge of what the design industry is gonna turn into. [OBD] gave us a lot of freedom to do a lot of creating on our own and to form the organization. It was forming and becoming its own thing as we were moving down the track.4

Stallworth: It was a super exciting time to see the development of an idea become a living, breathing organization with annual conferences, chapters, exhibitions, and increased recognition of designers of color. The momentum gained strength. OBD was getting calls from publications to showcase designers of color. David was asked to speak at conferences. I was asked to write a monthly design column on diversity in design for an industry publication. We were getting calls from designers all over the globe thanking OBD for providing a vehicle to meet other designers from all disciplines. The synergy was electric.”

Source: Core77

Part II: “I was just awe struck by the large crowd … and seeing so many faces like mine.”

Lawrence III: I believe a design studio owner named Antonio Roberson was OBD-DC’s first president after the “Dogon to Digital” event. We held meetings the second Tuesday of every month that were attended by anywhere between 10-15 people. I usually attended with my boss Rodney [Williams]. I don’t recall many events coming out of those meetings back then, but maybe since I was not in the leadership, my attendance and attention were not what they could have been. Those meetings were mostly about networking if I can recall, and the chapters were still trying to figure out how much we should rely on the national chapter for guidance. We did elect to have conferences every other year during that time. The second event was in Atlanta in 1996, the next was in Philadelphia in 1998, and then there was one in Los Angeles in 2000. The two California chapters in San Francisco and L.A. lobbied hard to get OBD to come to L.A.. The L.A. conference was great, but there were a lot of distractions and other things to do once you got to L.A.. It was a chore [to] keep everyone focused on the conference.

Stallworth: To date, I still get comments from designers talking about Dogon to Digital. We descended on Chicago with designers from everywhere. The conference programming set a new tone for pairing professionals from different disciplines – we had musicians with designers, artists with historians… the intellectual discussion was extremely high-level. The word got out and the conference was so well-received, the Chicago Tribune sent a reporter to the conference and the OBD Dogon to Digital conference was the entire front page of the Tribune’s business section on the following Tuesday, October 11, 1994. It was amazing.

Bass: I was to be on a panel of two speakers talking about promotion, but this conference [in 1996] was now an anorexic shadow of the one I first went to in Philly. The other speakers dropped out and I was the sole one left. Attendance was anemic at best, and I wondered what the hell did I get myself into. Considering I came out of my pocket for this as well — there was no honorarium nor was anything paid for: hotel, air, or conference registration — I felt like a sucker because they got the dream deal while I got nothing out of the experience. It was supposed to be a large student presence for portfolio reviews, but when the day came, it was embarrassing to see such a low turnout. They talked about doing another conference in Atlanta, but I knew I didn’t want to be party to any of this going forward.

Source: SoulFul Design

Walker: In 2012, I had an opportunity to work as the midwest coordinator [for OBD] where I went to cities like Cleveland, Detroit…places like that. [We] had events and [were] just trying to see where the pockets were. I really liked a lot of the work that OBD had done in the past. That is why I was so excited to be involved. That’s why I pushed so hard, especially in Cleveland, to do something about it. I know that they haven’t been as active this last couple of years. I know that David and Keir Worthy–who also served as the executive director…it’s kinda just them two, you know? Them against the world leading the charge. I wonder is it enough?

With just [Worthy and Rice], will they be able to answer all the calls? Will they be able to do all the design? I understand that David Rice is an industrial designer by trade. So putting together a social media campaign may not be his forté. And because of a lot of challenges that he has had in this “war,” I wonder. I’ve heard there’s supposed to be this conference that they’re trying to put together, and…I don’t know.5

When I was doing OBD, I had put together a list of activities. But these were more local things. David explained to me that what OBD needs is to be able to reach the masses. We need big things that generate dollars and revenue so that we can continue to even move the ship down the river. That’s where a lot of my angst comes in because you want to help out however you can.6

At the last conference, which was in 2012 in Cincinnati, I had people from Cleveland come and participate. People from Cleveland, where I had been having these smaller kind of events — they were really, really excited. So when one million Black designers didn’t show up, it was a little disappointing.7

Part III: “We needed more staff to handle this ever-growing organization.”

Lawrence III: Of course, there are [challenges] with any organization that grows and matures. With OBD, there was always the challenge of making sure all of the chapters across the country were on the same page with events and the kinds of content they produced. The New York chapter splintered off pretty early and did their own thing. I believe that was tough on the organization’s leadership. Also, once an organization starts to grow, it needs to solidify bylaws, org charts, a reporting structure, a voting body, etc. Those were things ODB seemed to struggle with in getting consensus. Eventually other chapters started feeling frustrated, and feeling they were not being heard.

Stallworth: At the outset, things were moving so fast and furious. We needed more behind-the-scenes staff to handle the multitude of requests, to answer questions and to provide accurate and updated information to folks seeking information. People were calling from all over wanting to start chapters. At the time, we needed more staff to handle this ever-growing organization. David and I worked day and night to keep up with the demand.

OBD is still needed, but [it] has gone more virtual, probably due to this robust shared economy. [There are] changes in how we communicate, transmit information and share professionally, as well as personally, via social media. David is still at the helm of the organization, and I’m sure he’s focused on what’s next.

Bass: Over the years, OBD’s reputation has tanked due to a number of reasons. My personal interactions with them have been mixed at best, and honestly, I kept helping out in the hopes that things could get on track. In the end, I realized nothing was going to change because for it to really change, it would have to undergo a massive overhaul in leadership, structure, purpose and content. Whether they realize it or not, blame for where it stands belongs equally to the founding core and [to the] members who both backstabbed one another.

Source: Carbon-Fibre Media

Part IV: “The need is so great that I often wonder how they will fare in this journey.”

Stallworth: Constant and consistent visibility of designers of color must continue. We live in a global world that welcomes people from disparate backgrounds to collaborate on everything. OBD can be a strong force in granting scholarships for students wishing to pursue design careers; establish lasting mentorships with students and professionals; as well as continue to promote the power of design.

Wilkins: OBD continues to evolve — which is necessary for growth — yet it has remained true to its core mission of identifying and uplifting African-American designers and other designers of color who are devoted to the discipline. David Rice continues to do an amazing job maintaining this platform where [African-American designers] and other designers of color are sought out, recognized, promoted, and showcased. OBD has created resources that help designers of all disciplines in finding employment and other professional services. David and OBD have made tremendous progress in procuring funding and sponsorships from supporting organizations and major corporations who see the value of and appreciate the contributions of African-American designers and other designers of color.

Source: Organization of Black Designers

Source: The Real Deal

Lawrence III: OBD still provides me with support through the connections and spirit of connectedness it has created. I gather with many of my OBD-DC Chapter colleagues to discuss that state of design and exchange information now. We met this past January and are planning another get together soon. Through OBD, my tapestry of support from the community has been enriched and continues to be enriched and broadened.

With new tools to connect each other and new ways to be activist, OBD should evolve with the times. Partner with other organizations on events and causes. Expand its reach through events and outreach. I believe the need is still there. Designers of color still need that network. It helps all of us stay connected and supported. Right now, OBD is still creating events and buzz but needs to reconnect on the grassroots level. Get active locally in each design community. The need is still there.

Bass: For OBD to be of value to all generations of Black designers, not just current, they have to be a beacon of solid stewardship: content and resources to help grow your career; help start and nurture freelancers/studio owners; help navigate the design industry particularly as designers of color; create solid events that expose design leaders that are invisible in the mainstream design channels; provide reliable and quantifiable job leads; and align with mainstream design organizations to help early introduction of the design discipline within the educational system.

Some of these things are being done by other organizations that are working together like AIGA and Inneract Project. At this point, I don’t know if OBD can serve designers of color.

Walker: I think there has to be a mix of big David Rice type of events where we get big time sponsors and get big hotels. On the flip side, we gotta have some of these smaller events. Much smaller, multiple events.8

We need places like OBD to be at these schools. But we have to be able to do that together. I guess that’s what makes me a little nervous about OBD — there are so few people who are pushing the boat. Are we united enough now to move the boat?9

The need is so great that I often wonder how they will fare in this journey. There’s so much work to do with Black designers.10

1 Leon Lawrence III, Revision Path, 22 Dec. 2014. </leon-lawrence-iii/>

2 Lawrence III, 2014.

3 Jacinda Walker, Revision Path, 11 Aug. 2014. </jacinda-walker>

4 Lawrence III, 2014.

5 Walker, 2014.

6 Walker, 2014.

7 Walker, 2014.

8 Walker, 2014.

9 Walker, 2014.

10 Walker, 2014.