Mike Monteiro screams and yells at audiences about gerrymandering and gets paid for it.

Stefan Sagmeister had lecture details carved into his body with a razor blade, then used a photo of it for a promotional poster.

Jessica Walsh and Timothy Goodman documented their forty days of dating and were invited to speak on the TODAY show.

Can the everyday, quirky Black designer get away with this? In order to be recognized in the design industry, one has to be willing to take risks. History always tracks the eccentric and iconoclastic Black artist who pursues their own vision. But unlike their white counterparts, are Black designers risking — or being rewarded in — their professional futures by being odd?

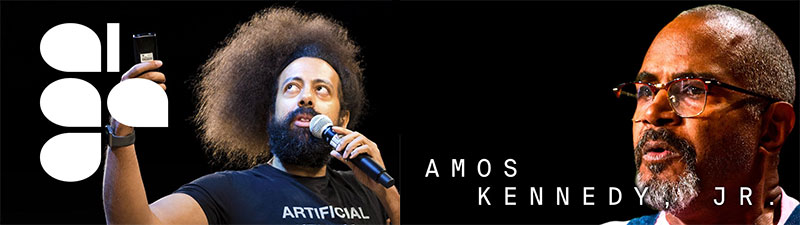

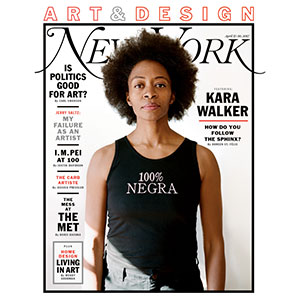

There are plenty of Black creatives who exemplify these characteristics. When I think of Black artists who exemplify originality and high visibility, former editor-at-large for Vogue Andre Leon Talley, silhouettist and installation artist Kara Walker, model/musician/performance artist Grace Jones, and the late painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, come to mind. Within design, I think of comedian/actor Reggie Watts and printmaker Amos Kennedy, both speakers at recent AIGA national conferences.

Reggie Watts, Amos Kennedy

All these creatives exhibit a unique combination of fearlessness, ambition, and savvy. And they have found great success in their respective fields by becoming iconic, highly-valuable brands. So the question isn’t a matter of if Black designers can afford to be weird. The question should be this: What can the design industry do to maintain and support platforms for Black creatives to fully express themselves? How can we ensure that Black designers feel safe expressing their idiosyncrasies without shouldering the burden of representation of their entire community?

Kara Walker

Privilege, bias, and other external forces of discrimination (racism, classism, colorism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, etc.) inform our inability to recognize extraordinary Black talent that just so happens to be a little eccentric. Black professionals, for instance, often cite having to code switch to fit in and be accepted. But it takes acknowledging that these assumptions operate within us in order to dismantle them. In order to learn new behaviors, one has to want to unlearn old ones.

Within these external barriers, we can continue to expand platforms for Black designers within the design marketing circuit. That starts with what someone is thinking when they invite Black talent to the table.

If you are planning a design documentary, conference, panel discussion, art exhibit, podcast, or interview series, invite several Black designers so they do not become the token Black person. Invite Black women and trans men and women. Their perspectives in the design industry are sorely missing, and they experience the industry in a number of different marginalized intersections that other groups may not. (And pay Black professionals at a fair rate for travel and accommodations. Presentations are labor.)

If you are not going to include Black designers in the planning process, do not bring them in at the last minute when time, money, and resources have run out. If you do this, do not be surprised if they reject your invite.

This is also important: do not include these incredibly brilliant creative professionals only to offer their exclusive perspectives on their gender or sexuality. Black designers are not a monolith; they come with a variety of skills, and that should not hinder their opportunities to offer knowledge, insights, and experience about their work in the space. For example, I attended the Design + Diversity Conference last summer. It was not solely focused on Black designers, but it fostered an openness among speakers and attendees that I find incredibly rare in the graphic design industry.

Kanye West

Finally, let us make sure we are not misrecognizing weirdness as irrational anger or hostility, but as honest personal expression. Remember when Kanye West was used as a case study by a Washington University professor about mental illness? While mental health is important, we cannot conflate an inability to articulate their ideals, philosophies, or creative ambitions as a potential cry for help.

Black designers should no longer have to ask themselves if they can afford to be weird. I would argue that it is actually beneficial to embrace one’s inner characteristics. That is what makes all of us genuine. The problem appears to be the structures that fail to recognize, showcase, and elevate Black designers’ authenticity. The design industry likes to see itself as the vanguard in fostering creative, alternate visual communicators. But if the industry is really that innovative, then it would show that by elevating outsider Black voices wherever possible.