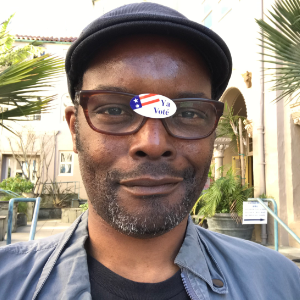

Maurice Cherry:

All right, so tell us who you are and what you do.

Eric Bailey:

Well, my name’s Eric Bailey, and I’m a design lead. I lead a team of designers at a company called Zillow, and I’m also a graphic artist.

Maurice Cherry:

How has the year been going for you so far?

Eric Bailey:

It’s been going really well, not without its surprises. I think the big lesson in the last year and a half has been just be flexible, you know?

Maurice Cherry:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Eric Bailey:

And be open to change. And so I would say that’s the one thing I’ve really learned is just be ready to expect the unexpected given the pandemic and given just changes in life that we can’t control. So be flexible and be ready also to take advantage of opportunities as they come up. But in general, me and my family, we’ve stayed healthy so we’re really, thankful for that. And yeah, and just really working through the different ways now that we interact with friends and family and also the way we work has changed shape for us. And so, yeah, I would say lots of silver linings for us.

Maurice Cherry:

Nice.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, I got to spend lots of time with family, really meaningful, deep time, things that we would probably never be able to do or have in any normal circumstances, so I have no complaints.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. I mean, this past year and a half, I mean, I guess really coming up on two years now that I think about it, it has been transformative in many ways. I feel like that’s the most apolitical way that I can state that. It has been very transformative. It has changed all of us in many different ways that I think we will still be unpacking hopefully years after this time has passed. There has definitely been a general shift in the collective consciousness that I don’t think we’re going to just snap back from.

Eric Bailey:

That’s right. That’s right.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. Yeah, it’s a great way to describe it, is just transformation in every aspect of life. And so, yeah, it makes you realize that you have to become, I guess, a being of transformation, right? You have to be able to change yourself too so that you can adapt. So, yeah, adaptation has been, I think, that keyword for me.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. It’s the only thing constant in the world, change.

Eric Bailey:

That’s right. That’s what it is. Right.

Maurice Cherry:

Let’s talk about the work that you’re doing at Zillow where you are a VP of UX. How are things been going during the pandemic with the team?

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, no, they’ve gone well. The pandemic created a big threat to human beings and our way of life, but also to business. And so, there were some real questions about how Zillow as a company or the real estate industry, in general, was going to fare. I think that because the company, Zillow that is, is really part of the technology frontier around real estate, automating processes, consolidating processes, Zillow actually did relatively or very well during the time. There was lots of activity, lots of engagement with the business, one, because now people are doing so much online, and then, two, because they’re starting to think about how the pandemic might shape where they live and how they live. And so, that was a boom to the business.

Eric Bailey:

I would say to the design team and I think the workforce, we really took seriously the taking on remote work as the de facto way we approach our day-to-day. And that was a big shift. That was something that was, I think, we entered with real interest and did deep research with the workforce to get a sense of where their sensibilities were. The overwhelming majority felt like remote or having at least the option to work remotely was preferred. And so, we’ve done everything we can to really put in place processes and tools and even aspects of our culture structured around remote work and asynchronous work. And so it’s really interesting. I think, great, lots of benefits, obviously, right? Now we can work with folks from many markets, many regions. We have really now diverse teams when it comes to that. Obviously, people don’t have to commute as much. So lots of benefits there. But there were some trade-offs too.

Maurice Cherry:

What sort of trade-offs?

Eric Bailey:

I’ve been at Zillow for about three years, and I was a part of the team that was localized into an office, and now I’m part of a team that is distributed and virtual. And so, having experienced both, I would say one huge benefit of being in a physical space with folks is really the kinds of bonds you can build. I think that, eventually, we will need to, even with a remote workforce, we will need to create time together. We’ll be making plans for team offsites or onsites, I guess, and team meetings and really strategic moments for us to get together and collaborate. And that will be around problem-solving, but also mostly it’ll be around just building relationship and community with our team. So being in the same place just really does allow people to really get to know each other, I think, in a way that it’s difficult to do online.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. How many people are on your team?

Eric Bailey:

I have about 22 people on my team. I lead what we call an experience area. And that experience area is called buy, sell, and transact. We’re focused on creating end-to-end experiences that support someone’s ability to buy a home from Zillow, Zillow sells homes, to sell their home to Zillow, and the transactions necessary to make that happen. So all the way through closing. And so I lead a team of product designers, essentially, that focus on that. And then I partner with research, user experience research, and content strategy. We partner to create those experiences.

Maurice Cherry:

Nice. It’s interesting. I guess, over the past maybe year or so, I’ve talked to other design leads, and it’s really interesting to see how content strategy has… or really content in general, written word has become more of the design process to the point where they’re considered designers or they sit on a design team in that way.

Eric Bailey:

That’s right. Yeah. Well, hence the word strategy in there, right? So not just writers, but these are folks that are creating strategies for basically touching and building bridges with customers, particularly when we are creating experiences that are either unprecedented or our customer base is unaware of, right? Most people know Zillow because of your ability to dream and shop, you come and look at homes, and you look at your neighbor’s home and how much they pay for it and things like that. But then there are all these other services. Well, you can actually sell us your home, or you can actually buy a home from us. These are things that less of our customers are aware of. And so, to really reach out to them and connect with them, we really need to be strategic about the way we communicate. And that’s more and more of an imperative for our business.

Maurice Cherry:

Have there been any particular insights aside from just, I think, team makeup and asynchronous work and stuff? Are there any particular insights that have arose over the past year now that the team is distributed?

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. Well, one, remote work for some companies is old hat, but for Zillow, a company that’s, I think, we’re 6,000-plus, a large company like ours, I think we’re still navigating how you build culture, how you sustain culture. I think the company has a really strong and rich set of cultural values, and it’s very good at holding one another accountable and living up to those values. But then there’s sort of the unspoken things. In a virtual world, I think maintaining the joy of your experiences is something that requires a real attention and real intention. And so, our design team has spent a lot of time, especially our design leaders have spent a lot of time really trying to be creative about, “Well, how do we keep our team engaged? How do we have fun at what we do in lieu of having a space where you can improvise, right?” And so, we’ve really been experimenting and there’s still lots of work to do there. But sometimes it’s important just for us to get together and have fun.

Eric Bailey:

The amount of effort and energy that actually goes into architecting those is pretty large. That’s, I think, a big insight for us.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, I didn’t know Zillow was that big. 6,000 people?

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, don’t quote me on the exact numbers. But yeah, we’re-

Maurice Cherry:

In the thousands.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. And that’s because we’ve grown from this online platform to now a broad range of services and products. We’re a lender, so we offer mortgages. We have rental experiences and services for landlords and for renters. So just a really now a broad range of experiences around the home. And so in that, lots of different service providers under one umbrella.

Maurice Cherry:

I know a lot of people have been moving or downsizing or just changing up how they’re living because of the past year and a half or so with the pandemic. It’s interesting. How has Zillow helped to facilitate that outside of, I guess, what it’s for, which is real estate buying, selling, and searching? I don’t know, I guess I’m wondering, are there any particular ways that Zillow has helped out during this time in that process?

Eric Bailey:

For its employees or for just in the world?

Maurice Cherry:

For the world, yeah. For the world.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. That’s a great question. Well, there’s definitely this migration, right? The economists talk about this migration from urban centers and across state lines. Many folks now are not bound to a specific region to make a living, there’s an influx of movement of folks that are moving to other states. Some are moving back to the states they came from, right? They would’ve been centralizing in Silicon Valley and in Seattle, but now maybe they’re going back to the Midwest or maybe they’re going back South. So huge migration there that is, obviously, an opportunity for Zillow.

Eric Bailey:

But also there’s this multi-generational trend, right? We have now families that are thinking about, “Well, I should probably live closer to home or maybe even with my parents or even grandparents.” So there’s also an influx of folks coming together and actually buying homes or bringing families under one roof. So really interesting market trends. We have internal folks that look at this, but those have been some of the big macro trends that I think are really interesting. And then obviously just doing everything remote, the fact that you can now actually sell your home online, you can purchase a home completely online or almost. There are a number of companies also they’re springing up around this capability. But yeah, the future of buying a home and finding a home is going to change dramatically over the next five to 10 years.

Eric Bailey:

It could be very similar to something like trading in your car, right? You drive into the dealership with one car, you leave with a loan and a new car, and you’ve left your old car. It’s all just one stop where you were doing that, you’re solving that problem for yourself and you’re focused on that thing that you want to buy. That should be the experience of buying a home, and eventually, it will.

Maurice Cherry:

Wow. What does a typical day look like for you?

Eric Bailey:

Typical day…

Maurice Cherry:

Does that exist?

Eric Bailey:

No. Well, yeah, right, no day is typical. It’s interesting. I think for me and my team, there are a few things. One, we work really hard to try to package our meeting times to a very specific timeframe. So between the hours of 10:00 and 14:00 are when we try to make sure that our hours… this is when we have core meetings. One, it’s to accommodate for multiple time zones. But it’s also to make sure that the other times outside of that are considered flexible and should be focused on getting the work done. And so, that’s a practice that we are all trying to employ and adhere to, or live up to.

Eric Bailey:

On a day to day, there’s probably logging in in the morning, attending some meetings. There would either be team meetings. There might be critiques for the design team. They’re usually planning meetings, some meetings that are about the work that we’re going to do in the future. And then there’s usually heads down working time. And yeah, I think some of the meetings if you’re getting together with a team you might be working on a project, you might be in a sprint, so you’re working at some point in the sprint process like you’re ideating or maybe brainstorming. And so, we’ll be doing some sort of remote activities, collaborative exercises to arrive at some outcomes there with teams. There’d be multifunctional teams, so product managers, designers, engineers, even folks from marketing, and obviously content and research. But yeah, now it’s mostly online, whether it’s collaborative or heads downtime. I think that’s how I’d sum it up.

Maurice Cherry:

You mentioned earlier about the challenge with building culture and maintaining joy. How have you been able to do that with your team specifically?

Eric Bailey:

I think I have two teams. I see myself as a part of a group of peers. I partner with other product managers and engineers and folks that are cross-functional. And so, I do what I can to create somewhat of a culture there. And then I have my working team, my team of designers and design managers. But in terms of design and design managers, some important things are maintaining my one-on-one. So I have weekly one-on-ones with all my direct reports. I have two team… They’re not critiques, they’re really focused on having the team share their work at earlier stages to get coaching. So it’s less about giving direction and telling someone to make it blue instead of agreeing and more focused on changing the arc of their thinking. So pressure testing their strategy and the questions they’re asking and the answers they’re coming up with. So those, I would say, are two review meetings where leaders are giving feedback to the design team.

Eric Bailey:

And then there are monthly meetings. We have a team monthly meeting. We’ve opened that up as open format to make it… We let folks from the team lead it. And so, there’ll be someone who’ll volunteer and sometimes they’re workshops. Sometimes they’re about learning. Sometimes they’re about problem-solving. Sometimes they’re about bonding or connecting, but there could be a range of things. But really the meeting is the operating system or the lever you have to create culture.

Eric Bailey:

I mentioned that other team and the other team is those cross-functional peers. And a lot of what I try to do there is really break the frame of your standard meeting format. When I’m leading meetings, I’m trying to make them interactive and make them conversations. I want them to be generative, so a lot of times I’m asking people to use the right side of their brains, folks that aren’t necessarily used to doing that. So giving them really solid provocations and asking them to think big with real big boat-like, “How might we,” statements?

Eric Bailey:

And then also done even some silly things like role play. I played Lori Greiner who’s one of the sharks from Shark Tank. We asked cross-functional teams to create concepts, and then I played a shark and evaluated the concepts, and they had to pitch those ideas to me. So even just trying to bring some humor into an otherwise what can be a, I would say, less than exciting format to computer screen.

Maurice Cherry:

Did you wear a long blonde wig too?

Eric Bailey:

I actually had a cut-out of her face. [inaudible 00:20:49]. And then actually before they came, I got them excited about it. I told them that we were going to have a guest actually, that Lori was coming. And so I’m a VP, so everyone thought, “Wait, maybe he knows her, maybe she’s coming.” They really got their pitches together for that, and of course, yeah, they got a big laugh when I came on with the mask.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. No, that’s good. I mean, that’s one of those ways that you bring joy is to just shake it up a little bit, you know?

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, and not take yourself so seriously. We can’t do that, right? We have to have fun and remember that we’re human beings.

Maurice Cherry:

I think more so than, I mean, just being human beings, we’re all human beings that are now going through this shared kind of traumatic experience. And so, I think anytime that when you’re at work, when you can let that facade down of it being so serious and just open up and be human, I think that’s what everyone just appreciates that now more than ever, I think.

Eric Bailey:

That’s right. Yeah, be authentic, your authentic self.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, when you initially booked the interview, and people that have listened to the show noticed this, that I always ask this question about what do you want people to take away from the interview? And one of the things that you had mentioned early on was that UX is a field with limitless possibilities. Of course, you’re AVP of UX at Zillow. Can you expand on that for me? How, from your perspective, is UX a field of limitless possibilities?

Eric Bailey:

For those that know me, they know I’m really into self-actualization. I really come to the realization that my purpose is to create user experiences that help people become who they hope to be. And those would be experiences that end customers or users would use, and obvious industries are healthcare, education. In this case, it’s finding a home, right, finding a home is both existential for people, but it’s also aspirational. You can change the arc of someone’s life in finding a home. And then it’s also through my teams, right, creating experiences for them that help them become the vision of who they see in the future. I develop over the years, and I can talk a little bit more about that later. So I think humans have a limitless possibility, and I think that the design field is really the perfect platform for that. It’s a perfect sort of Petri dish at least for creative people to discover who you are, who you want to be.

Eric Bailey:

That’s because of a few things. I think, one, it’s really, really broad. It’s open to so many different kinds of talents. So we mentioned content, so people that are writers, people that are researchers, that are inquisitive and empathetic, people that are artists, and people that like to make and create, and people that are builders and people that are analytical. And so it’s just so open to the array of skillsets that it’s so welcoming, I think, to so many folks left and right-brained that I think it’s an incredible career. I started out as a graphic designer, but UX really is this thing that is multidisciplinary. Yeah, I think it’s a really rich field.

Eric Bailey:

I think some of the skills that come to mind for me are there’s research, there’s synthesis, there’s storytelling, there’s facilitation, there’s interaction design, there’s service design, visual design, prototyping, right? These are all things that a user experience designer might be asked to do. And that doesn’t mean that you have to be an expert in all of them, but chances are you are going to bias us towards one or two of those, and you’re going to become an expert. You can have a team that has certain expertise in any one of these dimensions or two or three, I think is incredible.

Maurice Cherry:

It’s really been interesting how really UX has exploded as a field over the past few years. Of course, you’ve got General Assembly and you’ve got other types of boot camps and other programs that are really cranking out UX designers into the industry at the same time as the design industry has gotten more lockstep in with tech. Companies have went from being just strictly visual designed and now being more product-based. And so, the market has changed, and to that end, the workforce has changed to go along with that. So I can see how those possibilities are really there because a UX designer can be called six different things for six different companies.

Eric Bailey:

That’s right. That’s right.

Maurice Cherry:

They could be UX, they could be product, they could be-

Eric Bailey:

That’s right.

Maurice Cherry:

… like you mentioned before, content, things of that nature. And so, it’s really flexible in that way.

Eric Bailey:

It is. Yeah, it’s incredible. And like I said, it’s welcoming, right? That means it welcomes folks that are the anthropologists and ethnographers. It’s just a really diverse field. I don’t know of another one that is as diverse. One other thing it’s really important to note is there’s real symmetry between the design process and new ways or progressive ways of learning. The field of education right now is really embracing the design process. You have a question, you go out and get answers to that question. You form a hypothesis, right? You answer that question. You experiment with your solutions. You validate them, and you learn from it. That is the basis of learning, and here is a field that you can do that every single day. Every single day you are applying progressive learning, and you’re following basically this process. You’re continually learning throughout your life. And that’s one thing that I just find really fascinating is that they’re really the same thing. That’s incredible.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Now, you’ve mentioned before about being a graphic designer. To that end, I want to really go back and learn more about your origin story. Tell me about where you grew up.

Eric Bailey:

I grew up in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

Maurice Cherry:

All right.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. East Side.

Maurice Cherry:

We’ve got a lot of Ohio folks, specifically Cleveland, on the show. I’ve even got some family, they’re in Cleveland, they’re in Youngstown, they’re like right around that area. Yeah.

Eric Bailey:

Yes, that’s right.

Maurice Cherry:

Cleveland’s a great design city too.

Eric Bailey:

I think so, yeah, and we always represent. It’s an incredible town. Well, I grew up drawing. I loved to draw. I loved comics. I grew up creating characters and writing comic books and things like that.

Maurice Cherry:

Oh cool.

Eric Bailey:

I think my parents put me in some classes at the Cleveland Institute of Art. They have an industrial design program, so it’s the first time I saw these models of people making, basically, the cars of the future. I mean, Cleveland Institute of Art is a pretty top-notch school. It’s affiliated with the Cleveland Museum of Art, which is one of just a handful of world-renowned art museums, something that I was exposed to really early too. So, yeah, it’s a hidden gem in the Midwest, and a lot of talented people come out of Cleveland.

Maurice Cherry:

I was first there… When did I first go to Cleveland? I mean, aside from family stuff, but as a designer, the first time I remember going was in 2014. Yeah, 2014 I went. I spoke at a conference there. Damn, that was seven years ago, Jesus. But I spoke at a conference there. There’s a local studio there called Go Media, and they had this event called Weapons of Mass Creation. I don’t know if they still have the event. I don’t think they do, but every year they would have a number of different panels. It was a multi-day event. They would have live painting. They’d have break-dancing. It was a whole thing, and that’s how I really got introduced to Cleveland as a design city. I was like, “Man, this is great. This is wonderful.” And got to meet other designers from nearby, from Chicago and from Detroit and stuff like. So it was great. I want to go back to Cleveland once all this pandemic madness stuff is over. But, yeah, sounds like your parents really kind of introduced you to design and exposed you to that early on.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. Yeah, definitely. I mean, they knew it was ordained that I was going to do something creative. I mean, I had been drawing since I was maybe two years old, and I would spend hours and fill up sketchbook after sketchbook. I just loved to be creative. Yeah, they just did what they could to expose me to different things. I didn’t want to be “a starving artist” artist. Obviously a stereotype, but I didn’t know what design was. But I applied to a graphic design program in Cincinnati when I was coming out of high school. So it’s the University of Cincinnati in graphic design in School of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning and-

Maurice Cherry:

Wow, it’s a mouthful.

Eric Bailey:

… really… Yeah, it is. DAAP is the acronym. But it was an amazing program. I think like many of my experiences, it was serendipitous. I just followed a calling, but I didn’t know what it was going to turn into. One, it was a five-year program, and two, it had a… First year was foundation, so you spend that first year with architects and industrial designers and fashion designers all doing the same thing, learning the same fundamentals. And then you break off into your expertise. And two, it had an internship program or a co-op program that wound up being six quarters in the field. So every other quarter I would-

Maurice Cherry:

Oh, nice.

Eric Bailey:

You wind up working the equivalent of a year and a half before you get out of school. And so that was an incredible experience.

Maurice Cherry:

I’m not saying this to date you, but this is-

Eric Bailey:

That’s okay, you can date me.

Maurice Cherry:

No, but I mean, this is in the early nineties, this is really prior to the advent of the personal computer and design really coming into its own through things like CorelDRAW and Photoshop and stuff like that. It sounds like, I mean, that sort of hybrid program of work plus in-class instruction was really good.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I would say anyone looking at design programs should choose or take very seriously programs that have internships, right? Just the amount of autonomy and independence and the amount of clarity I got on what I wanted to do and what I didn’t want to do was incredible. The other thing is as part of that program you move from city to city. I worked at the National Park Service working on the publications and brochures that they use in the national parks. I worked in St. Louis at a retail doing design for retail. I worked in Dallas, Texas doing environmental graphics at an architectural firm. And then I worked at a small but cutting-edge design studio in Boston. Every quarter I was moving to a city, finding an apartment, and either living with other students or living on my own and had a full-time job. I mean, it was incredible.

Maurice Cherry:

Wow. I don’t know if there’s really any design program like that now that really put you out there as a working designer while you’re still in school in that way.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, I think there are a handful, and they’re definitely worth you tracking down. I’ll any day hire someone from Cincinnati as an intern or full-time.

Maurice Cherry:

How was your early career post-graduation because it sounds like you’ve managed to gain a good bit of work experience while still being a student?

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. I definitely didn’t want to stay in Cincinnati. I came out of high school in ’90 and from 1995 was an undergrad. When you’re from Ohio, you do a few things. You either stay in Ohio, you move to New York, Atlanta, or Chicago. And so, I started applying to jobs in Atlanta and Chicago. I had some family in Chicago. I actually wound up a conference for The Organization of Black Designers. It was the first one, it was held in Chicago. Through that, I think I wound up landing some contract work in Chicago. So I went ahead and moved to Chicago. And then while in Chicago, I attended at a conference, and that really got me connected to a number of opportunities. But that was a really pivotal moment for me.

Maurice Cherry:

The Organization of Black Designers, wow. Revision Path and OBD kind of have a… I don’t know, I don’t want to say a history, that makes it sound contentious. But since I’ve started the show and I’ve been talking to people, the organization has definitely come up several times. I’ve tried to get David to even come on the show. But we’ve had other past folks that have been on the show, we did a whole oral history of OBD back in… Wait, when was that? 2018, I think, something like that. I mean, it’s just amazing hearing about how that organization came about it and really how many people it helped out because it’s something that I don’t think a lot of black designers even know about because it’s hard to really pin down-

Eric Bailey:

I know.

Maurice Cherry:

… that history. It’s not a story that’s like AIGA or something like that. I mean, you tell me because you were around, was OBD for the black designer back then?

Eric Bailey:

For me, I mean, one, I was probably maybe one, maybe two black students in my cohort, right? At least I would say I identified as black and that I was making it really clear I’m black. I kind of led with that. But very few in the design program in Cincinnati, very few… In all the internships, I was probably the only black person in all the internships, maybe one that I interacted with in the corporate environment. And then moving to Chicago and working at these firms, just seeing so few black designers. So this is the first time in my life I stood in a room and saw hundreds of black people that were creative that were just like me, and fashion, art, graphic, industrial design, you name it, architects. To do that for the first time is transformative. You just realize you’re not alone.

Eric Bailey:

So I think that’s what it did for me, just make me feel a sense of belonging in a way that I had never felt before and realize even if I do go back into these other spaces and I go to my nine to five at this company over here where I’m still the only black person, I know we’re out there, and I’m validated by that. I know I have a lifeline to them. I can always touch base with them. A lot of what I was doing was taking the people on that list and calling them up and saying, “Hey, I’m looking for work.” So a lot of it was pre-Linkedin, just using that network to see if you can make inroads and either get a job with them or have them refer you.

Maurice Cherry:

But right around that time, you also got involved and helped co-create something called Project Osmosis. Can you talk about that?

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, this is part of the oral history of OBD. I think I had the fortune of meeting some of the folks that after that initial conference in Chicago, there are designers there that convened themselves on a regular basis from that point on and kind of became the Chicago chapter of OBD. And that was led by Vernon Lockhart. You met with him before. He really helped coalesce a team of folks that we call ourselves OBD, Chicago, and we were representing OBD and that chapter. And so I was attracted to that group, so I joined them and had other friends that joined. And so, we got really close and just really bonded and tried to carry on the legacy of the larger org to both network, but then also to try to do some more outreach to the community and primarily to younger folks.

Eric Bailey:

And so, that outreach was through University of Illinois Chicago. We were doing programs either with students there or through local high schools, middle schools. I also did a little bit of internal visioning and journeying and we together came up with this idea of more like an outreach, like a consistent outreach to creative youth that would eventually enter the design community. And so, the idea was we know that there are creative folks out there that have this innate talent and they probably don’t see any pathway for themselves, right? They don’t see that there are these fields out there, these roads to success that they could take, and using their talent something that they could have fun and in joy every day.

Eric Bailey:

We wanted to expose more and more creative kids to these fields, to industrial design, fashion design, graphic, architecture, et cetera, and so we decided to create a program around it. There was this woman named Lisa Moran, Keith Purvis, Vernon Lockhart, Marti Parham. There’s a number of other folks, I don’t want to leave them out, but we basically came up with this idea of Project Osmosis. And that was, of course, these kids learning from the design professionals, and that was the genesis. We actually converted OBD Chicago into Osmosis. And that was its next incarnation; we were no longer OBD.

Maurice Cherry:

And shout-out to Vernon Lockhart. I mean, he is still keeping.

Eric Bailey:

Oh my gosh, yes.

Maurice Cherry:

… Project Osmosis going to this day.

Eric Bailey:

Yes.

Maurice Cherry:

To this day. Shout-out to him. Wow. So you were working for a few different design studios back then doing a lot of graphic design work. What do you remember the most about being a working designer from that time?

Eric Bailey:

It’s funny you mentioned the adoption of computers. I would say I was in my second year in college when we were using Mac computers and Adobe software. I was using those all through college and in my internships as well. And so, yeah, most of my work then going out, I would kind of… I think the first year or so I was a freelancer and I would use my network to see who’s looking for a designer, and I would join these small studios. There was a studio called Metaphor. There’s a number of others I can’t even remember right now. Pivot Design. I would just go work with them for a few months and work on mostly corporate communications and things for whatever local restaurants, whatever, doing mostly print work. But I wound up working at a small web design shop for the first time. They were working on websites, and that’s when websites and web marketing was just taking off. So this is 1997, ’96, ’97. And yeah, that’s when I started learning web design at this place called Streams Online Media. No longer around. And then I wound up joining a company called Giant Step, which was the digital arm of Leo Burnett, a larger ad agency, and so made my way into web design.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, it’s hard to overstate just how much of… There was nothing back then of web design.

Eric Bailey:

True. True.

Maurice Cherry:

There were maybe a couple of books, but even those felt like they were being written on the fly. There was just a lot of view source and figuring it out.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, absolutely, especially when it came to digital design. Digital design, it was a gamble, right? The paradigm for designers was you’re a graphic designer. You either work at either a large graphic design agency or you work at an advertising agency. And then you eventually become a creative director, right? Your Paul Rand was the prototype for your career. But I think digital, really those larger agencies didn’t have experience in that. So it was really the small tech companies and webshops and things like that that were really starting to hire designers and do groundbreaking work.

Maurice Cherry:

Because they could move faster because they were smaller.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely.

Maurice Cherry:

I remember, let’s see, ’97. I was in high school in ’97, and I remember that’s when I got my first HTML book. We had went to a… Was it a Walden Books?

Eric Bailey:

Walden, yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

It was Walden. We went to Walden Books in Montgomery. I’m from Selma, but Montgomery’s 50 miles away, so we went to Walden Books and got this big HTML book. It was orange. It was like a thousand-page book. I don’t know, back then, they had a bunch of books like this for different languages. There was one for HTML, one for ASP, different things like that. And I remember this big, huge thousand-page book, and I would carry that around with me at school. And whenever I got a chance to go to the like… We had a supercomputer lab in my high school, and we had computers in the library. Whenever I had free time, I would just go in with that book and I had a Tripod account, and I would just start trying to figure out like, “What does the blink tag do? What does the marquee tag do?” Just trying to figure out how it works. Because it’s one thing to see it in the book, but then to actually do it on the web and see how it works in real time, to me that was just such a transformative time in learning design. Because really there were no rules.

Eric Bailey:

That’s right.

Maurice Cherry:

You really could do what you wanted to do.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. And this is also when so many of those other roles were starting to enter the field, right. You might be a graphic designer who was usually doing comps and mock-ups and doing layout for, let’s say, posters or books or write other corporate communications that was like a… we’ll say layout, but then there were people who were technologists, right? There were people who are anthropologists who were becoming information architects. And so yeah, just sociologists and cognitive psychologists. So that now as a designer, you’re starting to interact with these people. They’re also people with backgrounds in motion design and film design, and so they were starting to come together at these companies. And so that was really interesting, was just now interfacing with such a range of creative people, whereas as a graphic designer you might interact with a photographer and maybe an illustrator. But yeah, really interesting.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. I would say for of those of us, like designers that are probably 40 and up, to really see how the entire design community has changed from those early days in the nineties to now, it’s been really inspiring to see just how much things have changed.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, absolutely. That is why I also say that UX or user experience is such an amazing field is just because it is really on the cusp of that Moore’s Law of continual transformation and change. It’s almost as if design is becoming something new, and UX is sort of, I think, on the forefront of that. So the fact that it’s, yeah, it’s constantly growing and changing it’s really exciting. It has a continual frontier, right? There’s a continual green field in front of it.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Now even with all the design work that you’ve done over the years, you also have your own side business, side project that you do that’s called Properganda. How did that come about?

Eric Bailey:

That’s a great question and great timing for that question because what we’re talking about right now, this moment for me was a time when I stopped doing that kind of work. So when I was an undergrad, I kind of… Really short story here, when I was an undergrad, I did really well my first year, my second year in school I started to get really just uninspired and really had a hard time understanding how… I was this black kid. I’m pretty much the only one in my program, there’s one every year in the program. Really felt isolated. How is Gestalt psychology and semiotics, and how are these things… Will they have anything to do with me, all these Western theories and things?

Eric Bailey:

And so, I even had a professor approach me and say… I had a really hard end-of-year review, and he pulled me aside and said, “I look around the city, and I see so many black folks basically. But then I look in the program and you’re really the only one. I would think that you would want to essentially represent your race… or represent your race better.” One, he was not black so I had no [inaudible 00:47:33].

Maurice Cherry:

Of course.

Eric Bailey:

[crosstalk 00:47:33].

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, that’s pretty wild to say. Yeah.

Eric Bailey:

I mean, it was a jaw-dropping moment for me. And from that point on, I was singed by that, like really burnt by that. But we had a project shortly after that where we had to take a word and manipulate it and have it mean something else, a typographic study. Something clicked at me and for some reason, I chose the word Thanksgiving. I started playing with the letters in the word.

Eric Bailey:

I started with red letters, and I changed one letter to white and another letter to white and another one and then started making the red letters disappear, and it started to simulate population. I started thinking about the reds and the whites and how whites move in and reds start dying off. And at the end I added, I just added an E to both words and wound up with the words take and give. And there was white take and red give at the end. So it was really just repeating the word Thanksgiving and changing the color of one letter each row. So the statement was obviously about colonization, about gentrification… well, not gentrification but genocide essentially and the Holocaust, American colonization, and was through a typographic study. And that was the first time I realized, “Oh, I can use the tools they’re teaching me to make the statements I want to make.”

Eric Bailey:

And from that point on, it took off for me. I really loved visual pun. I really loved to use really simple graphics to make a really hard-hitting statement. And so the rest of my career there in undergrad was really making really cutting, really socially critical statements in my work. And that was my way of pushing back on that professor and basically on my cohort.

Eric Bailey:

It was really liberating for me. That’s what got me excited about design, was that I can use this craft to make a statement. Most designers, you’re meant to be objective, you’re not meant to make a statement. You’re meant to channel, right? This was my ability to communicate. So of course, I graduated. I went into the workforce, entered corporate America, and I stopped doing that kind of work. And that was around the time we talked about when I moved to Chicago and started working in health. So fast forward probably 15 years, I was working at a startup. I was a lead of design and really uninspired. I was really unhappy. I was burnt-out. For those years, I knew that I was not fully self-expressed.

Eric Bailey:

One night, I took out some of the old pieces that I worked on. The first one I took out was Thanksgiving, and I just updated it. I redesigned it, refined it. And that was really me getting in touch with that old self through the craft of just reworking those pieces. I picked up another one and started reworking and kind of updating it. And then from there, I started making new pieces, and they were usually some critical statements. An obvious, easy target is social media. That’s one that I have a love/hate relationship with. So started making lots of pieces around social media and its impact on us.

Eric Bailey:

That was it. I just was creating for the sake of creating, and it really breathed life back into me. I was up until 3, 4, 5 o’clock in the morning, multiple nights just not being able to stop creating. That was kind of the genesis and coming back to that idea of Properganda. I had come up with that nomenclature in the nineties, and so I decided to bring it back and say, “Okay, I’m going to build something around this.” So Properganda it was.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, Properganda, I like that because, of course, back then, proper was part of slang back then saying something was proper. I’m curious, have you heard of the book Visual Puns in Design?

Eric Bailey:

Eli Kince.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Yeah.

Eric Bailey:

Yes, yes. Yeah. Tell me, how’s that top of mind for you?

Maurice Cherry:

Oh, God, a few years ago, I was really seeking out design books by black designers.

Eric Bailey:

Wow. Yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

I got his book. Saki Mafundikwa has a book called Afrikan Alphabets that is super hard to find, and I managed to get that. And yeah, that’s how I first found out about it.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. Yeah. I mean, that’s my jam. When someone can use the visual image to break expectation or to change perception and change meaning, I just think it’s so brilliant. He’s actually a University of Cincinnati alumni.

Maurice Cherry:

Oh, okay.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah, so he went to my school, he went through my same program, and he probably had that same instructor. Yeah, I love that sort of compendium of work that he collected there. I actually reached out to him maybe a few years ago when I picked Properganda back up. I was compelled to reach out and try to meet him. I think we chatted for a little bit through email. But, yeah, that’s so interesting you bring that up because that’s a really, I think, a great north star for me. Really impressed with this brother who, who was from my neck of the woods, basically,

Maurice Cherry:

I’m going to try to get him on the show. I reached out to him a few years ago too, and I think we were trying to get something going but he was busy at the time. So I’m going to try to pick that back up because that is a really good book. And for folks that are listening, you may be able to find it on eBay or Etsy. Because I don’t even know if it’s still in print, but I know that there are some copies of it floating around if you’re trying to find it.

Eric Bailey:

Yes. Yes.

Maurice Cherry:

So it sounds like having Properganda as that side project really helped fulfill you as a creative, even as you did your regular nine to five work.

Eric Bailey:

Yeah. I mean, I think it was I became really aware that my full-time work was not enough for me to be fully self-expressed and be fully self-actualized, and it was only going to be through doing that work that I would be my whole self. So from that point, it’s been a great ride. I mean, it’s hard. Like I said, I was compelled to do all that work. So I created a lot of work and lots of hours. I’m a full-time parent and have a full-time job. And so to do this as well, it’s a commitment. But yeah, it’s a part of me that has to be expressed otherwise I’m not fully myself.

Eric Bailey:

A lot of it is really not only just I have to create, I want to have that experience of creating. Because as a design leader and a manager, I create so little nowadays, right? I create success through teams, and my design is really people and their careers. And so then it’s like, “Well, but I still want to make things.” And so this gives me ability to do that. I call myself and this work the armchair activist, the person who walks through life, knowing that things aren’t quite right and just knowing something… It’s that whole matrix, right? You know that things aren’t right, but they need that tipping point. They need something to say, “Hey, look,” like nudge them and say, “You should be questioning this phone that you’re staring at for 10 hours a day. You should be questioning the things that you’re consuming. You should just think critically about your own behavior and how these things shape your behavior. So that what that’s based on.

Maurice Cherry:

There’s a designer I had on the show a few years back, his name is Andre Hueston Mack. He is a designer who had some experience in the financial industry but then later became world-class sommelier and now has his own brand of wines. They’re called Mouton Noir or Black Sheep Wines. His design, I don’t want to say it’s something similar to what you’re doing, but he also does these visual pun sort of designs as well. His design studio is called the Get Fraiche Cru, but fresh is spelled F-R-A-I-C-H-E like creme fraiche, and then cru is C-R-U, as in a vineyard because he does the wine. Actually, for people that are listening and for you too as well, if you all want to go to Bon Appetit’s YouTube channel, I know that that has had its own controversy, but if you go to Bon Appetit’s YouTube channel, he’s done a series of videos where he talks about wine and stuff so you can get to see his personality and stuff like that. But if folks want to check him out, I think he’s episode like… I want to say 313 or something like that, Andre Mack. It’s in the 310s from what I remember. I tend to remember pretty well who does what when. It’s a weird quirk, but if folks want to take that episode out, 313, it’s pretty good.

Eric Bailey:

Thank you for sharing that.

Maurice Cherry:

So between Properganda and the work that you do with Zillow and everything, and even, I guess, throughout your career, how have you worked to stay your authentic self?

Eric Bailey:

Well, I think Properganda is part of my authentic self, so even manifesting that. One, acknowledging it, “Hey, I need to pay attention to this aspect of my personality, and two, I need to feed it, and I need to make it public and build it around it.” Acknowledging that in myself, and I think that’s advice I would give to everyone, listening. I do a lot of internal listening. I usually do visioning exercises at least once every two years. And that’s to check in with myself on, “Okay, what experiences you want to be having and what skills do you want to be developing?” And so, Properganda is a manifestation of that. It’s like that happened in order for me to be whole.

Eric Bailey:

I think at work, a lot of it is around… Working from home was a milestone, something that I wanted to achieve. I just had the good fortune of things making that the case. For me, going into an office, commuting for three hours a day or four hours a day is not sustainable even though I’ve done it for 15 years. And so, having a better integration of home and life because home is the authentic me, so integrating that, that puzzle piece has fall fallen into place but that’s been important.

Eric Bailey:

I think also you talked a little bit about the last two years and not just the pandemic, but all of this sort of… I don’t call it social up upheaval, but it was just folks tired and pushing and being vocal. Whether it’s the protest or the election or whatever, but they’re the real issues about equity in our country and race. Those issues now have become part of the discourse at work and/or on in day to day. Now people are talking about things that they would rarely talk about or in spaces that they would rarely talk about. And so that is really important to maintain that. Now if I’m at work, we will talk about being a black designer or a black design leader or being a black male or a black woman or a black trans person, all of the diaspora and all of the issues that go with that, those are now part and parcel of the things that we talk about in work in our daily lives.

Eric Bailey:

So being authentic to that and putting words to that is really essential. I think I spent many years compartmentalize my blackness from work. And so, now that’s what part of being my authentic self and bringing that authentic self to work is that we can talk about aspects of my identity, other people can talk about aspects of their identity, and then we can talk about these things that go along with that. One thing is also working on things that are relevant to my own interests. Zillow is really pushing to create a social impact agenda and initiatives that are focused on changing paradigms in the housing industry and the fact that housing is kind of key center point around inequity, especially in [inaudible 01:00:47] communities. So being able to participate in work and help steer work, that’s focused on creating social impact, like doing that also is a part of my full-time job. It’s not just about paying the bills but being able to move certain boulders that are important to me in my life and then also being more and more myself. Those are the things I really push for, if that makes sense.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Do you feel satisfied creatively these days?

Eric Bailey:

I do. I do. I think my biggest challenge right now is probably I want to do so much more and there’s just so little time. The last year was tough because the kids were home during the day, so we were working and we were parenting. And so by the end of the day, it’s just like, “I’m done like toast.” And so, there wasn’t a lot of bandwidth to do other things. Now the only thing that limits me in terms of my happiness with being creatively expressed is just time. But I now have the things that I know I love to do. And so, yeah, I would say the answer is yes.

Maurice Cherry:

What do you want the next chapter of your life to be like? Where do you see yourself in the next few years? What kind of work do you want to be doing, projects, stuff like that?

Eric Bailey:

I think in the future I want to work to live, not live to work. And so that means that I want to work smarter not harder. I want to work on things that I’m really good at and do that with ease. And then I want to be able to take advantage of the benefits of my accumulated knowledge and expertise. So if I’ve worked for 25-plus years, I should be able to take the foot off the gas. And so, to be honest with you, it’s less about what new kinds of work I want to do and more about the balance I want to strike between work and life. I want to do less of busy work and logistics and administration and less churn and more generative and creative, and then also connecting with my family. I know that doesn’t directly answer your question, but, yeah, that’s the goal.

Maurice Cherry:

Well, just to wrap things up here, where can our audience find out more about you and about your work and everything online?

Eric Bailey:

They can find me on LinkedIn, so Eric Bailey. I think you’ll share some links there. I’m Properganda1, the number one, on Instagram, and then propergandadesign.com is a website for Properganda. Yeah, and there’s zillow.com. So you can obviously connect with Zillow and all the great things we have there for folks that are looking for a home, whether they’re renting or buying. And let’s see. Yeah, I think that’s not a huge digital footprint, but those are the things I keep it to.

Maurice Cherry:

All right, sounds good. Well, Eric Bailey, I want to thank you just so much for coming on the show. Thank you for, I mean one, sharing your story about how you really have become a designer and have made your way up in your career, but also really sharing how you’ve been able to balance these parts of yourself, whether it’s doing Properganda on the side, whether you’re building your teams. It sounds like you’re continually striving to have that sense of balance among the creative and the professional and the personal aspects of your life. And I think that’s something that all of us listening can really learn from. So thank you so much for coming on the show, I appreciate it.

Eric Bailey:

Maurice, my pleasure. Thank you. I’m really honored, yeah, just to be a part of a illustrious cohort of interviews, so thank you so much.