Maurice Cherry:

All right, so tell us who you are and what you do.

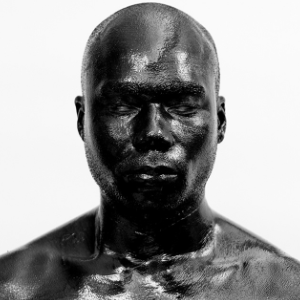

Branden Collins:

I am Branden Collins. I am an interdisciplinary queer designer, artist, inventor, archivist and performer from Atlanta, Georgia.

Maurice Cherry:

Nice. How has 2023 been going for you?

Branden Collins:

It’s been pretty good. I moved back from Atlanta…to Atlanta from Los Angeles. It’ll be about two years ago now. So over the course of those couple of years, I’ve just been kind of adjusting to being back here, being around old friends and reconnecting with people and sort of trying to re-establish myself in my practice here, which has been a journey. But I’ve been able to kind of kickstart a lot of new projects that I’m really, really excited about. So it’s been a whirlwind, but it’s been overall positive and really nurturing, nourishing experience so far. The year has been pretty good.

Maurice Cherry:

Nice. What’s been like the biggest thing you’ve had to adjust to?

Branden Collins:

Not being close to the ocean, I think that’s definitely the biggest thing for sure. Everything else comes with being in Atlanta versus L.A. Just typical stuff, but that’s definitely been the biggest adjustment.

Maurice Cherry:

I mean, the traffic in Atlanta is pretty bad too, but the traffic in L.A. is on par, I feel.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, it’s a toss up. You’d be hard pressed to say which one is worse, to be honest. The infrastructure in Atlanta definitely isn’t built for as many cars as we have coming into the city. And even in L.A., I think a city that was built for that is still a challenge. So being here is definitely pretty hardcore.

Maurice Cherry:

Well, you talked about re-establishing yourself and working with some projects. Can you talk about what some of those are? Is there anything that you want to try to do before the year ends?

Branden Collins:

So yeah, a few things.

I am working with a longtime collaborator and friend, Ami Swecki, who runs a creative studio called Zoo as Zoo. Her and I are working to build a platform called YOO, which is essentially at this stage, like a mind-mapping tool to help people of all kinds, but specifically new media, artists and creative technologists, to help them just organize their digital life, so to speak, all in one place. And sort of, in that way, help them sort of make new connections and curate their ideas towards the development of new projects and new types of technology. So that’s one of the bigger things that I’m working on.

I’m opening a bar with a good friend of mine, longtime friend Omar Ferrer. It’s called El Malo, and it’s going to be a really beautiful place and definitely a practice in world building for him and I and the whole team, which I’m working on Zoo with that as well. Really excited about that; about having our own space to have fun and enjoy.

I’m working on XR radio with Amiko — Sharon Oh — who runs her own studio, Polyvisuals. We’re essentially just trying to craft a story, a narrative about mixed reality and about identity and kind of through the lens of all of these technologies that all of us are sort of keeping our finger on the pulse about artificial intelligence and AR and VR and simulation and all these different things. Kind of asking the question, like, “what does it look like to exist in a world where all these technologies are integrated with one another” and having to navigate that? Sort of the way that we’re approaching it, as with all of my work, is really from an anthropological perspective, and I think recognizing that the tools themselves — the channels are new, the devices are new — but the questions and the challenges aren’t really that new. When you think about how we all navigate the world with the identities that have been in large part bestowed upon us, we have to constantly encounter manipulation and questionable realities and alternative facts and all of these things. We’ve had to do that for a really long time. It’s interesting to try to kind of craft a story around that with those things in mind.

So those are some of the kind of the big ones that I’m working on and everything kind of like circles around all of the rest of my work, which we’ll talk about more.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. So, yeah, you’re doing just a few light projects, nothing major.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, exactly. (laughs)

Maurice Cherry:

I heard about El Malo. I think I heard about it…I want to say maybe on it was one of these blogs. It might have been Water or What’s New Atlanta…Tomorrow News Atlanta? Something like that. But I think it’s going to be in Reynoldstown, I think.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, it’s at the Dairies. Yeah, it’s right in that little — not little — in that complex next to the Eastern. Yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, I definitely want to check it out because I heard it’s a rum bar and I love rum.

Branden Collins:

Nice. Okay. Yeah, we’d love to have you, man. I’ll give you a membership. We can just set it up.

Maurice Cherry:

Well, thank you! Yeah, I appreciate that. Let’s talk about your studio, The Young Never Sleep, which you founded back in 2010. I’m looking at the website and it’s described as “a platform for visual experimentation through collaboration and interdisciplinary design services,” which you kind of have spoken about already a little bit with some of the stuff you’re working on. Tell me more about the studio.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, so I started that in 2010. It was originally just the name of my blog on Tumblr. I think I just came up with that. I think rooted in this idea of, just like, the restlessness that comes with youth and with being just insatiable in curiosity, and that being kind of the driving force behind my work. So the name kind of stuck as a blog and then turned into the name I use for my creative practice. And, yeah, I’ve been using it as a platform, a network, so to speak, to collaborate with other creatives to expand our work, the possibilities of our work, kind of leaning on each other’s strengths and then using it as a way to work with clients, with brands large and small. And over time, it’s just continued to evolve and expand as a way to explore my own identity and just do cultural research and archiving. And it’s kind of ballooned into a much, much larger idea, which is exciting. Sometimes overwhelming, but it feels right, so I’m still doing it.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, what would you say kind of sets your studio apart from other studios?

Branden Collins:

I would kind of parallel it with what I appreciate a lot about Zoo. Zoo as Zoo — Ami’s studio — is, I think, we approach it slightly different ways sometimes, but I think we both understand, I think, the impact and significance of not just creativity, but creative thinking. And the way I approach it is, again, through the lens of, like, anthropology, science, nature, and this idea that creativity is something that’s inherent to nature. You know, start talking about technoculture. That’s essentially what that kind of practice and philosophy is about, is that these things are rooted in nature.

Like, when you look out at nature, animals express creativity. They do architecture. Animals have languages and dialects. Animals create technology. They make tools. They have tool use and do mathematics and experimentation. And it’s sort of like realigning ourselves with the fact that we are animals. We’re animals, too. And that’s like a thing to be an honor for us, that we’re a part of this grand story of technology that doesn’t just start with humankind. It actually just starts with the beginning of life itself, and that the creative endeavor is the same thing. It starts the story of creativity, and creative expression goes back as far as time itself. And that, to me, is a profound acknowledgment. It kind of drives the pursuit of the studio.

And I started using this banner — another world is possible — many years ago not knowing that it was an actual term in politics of alter-globalization which seeks to hold on to the positive aspects of globalization while sort of critiquing and, if necessary, discarding some of the negative aspects, which I found to be pretty perfect once I realized that that is what it actually was about. But it’s really rooted in a world building practice and this idea that when we look out at nature, nature has all of these incredibly innovative solutions to so many complex problems. Using that logic, it’s quite simple that the world that we live in, with all of its kind of multitudes of injustices, is just one world. It’s one possible outcome based on things that we all should know about. We know why we arrived to this destination, because our map was constructed in a certain way. So if we start to retell the story and start to change the map, then the histories and the futures that are available look totally different.

And that, to me, is exciting. And that’s sort of the power and potential of creativity.

Maurice Cherry:

As you’re talking about this, you’re reminding me of an interview I did several years ago with Billy Almon. Billy Almon, he’s an inventor also. He’s an astrobiofuturist.

Branden Collins:

Yes. I love that.

Maurice Cherry:

And a lot of the work he does is around biomimicry. Some of what he does kind of speaks to what you’re talking about in that looking to the natural world on ways that we as humans can kind of live in this world or solutions, things like that. His premise is that the natural world kind of has provided all the solutions that we need. If we just look for them or look to them, I should say 100%.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, absolutely.

Maurice Cherry:

And also, your studio is a collective. Like, you’re working with partners. You’re working with other collaborators too, right?

Branden Collins:

Yeah, absolutely. I’m always working with other people. As much as I’m doing independent work, I’m constantly working with other people. Most of the work that is shown on the website and on my Instagram is collaborative, and I try to stress that point that collaboration is really key in certain instances and necessary to actually expand my capabilities and the capabilities of the people that I work.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, and I’m looking at the site…I mean, you have a very impressive list of clients and collaborators. I’ll list off a few of them. Medium, HBO, Nickelodeon, Impossible Foods, and even some, you know I was saying before we recorded, I was like, “I’ve seen your work before. I knew that it was from you.” But like Bon Ton, which was this…I think it’s Bon Ton is still in Midtown. I was thinking of TOP FLR for some reason, but Bon Ton is below TOP FLR. TOP FLR is now something else.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

But also, you did a lot of work for Brittany Bosco.

Branden Collins:

Yep.

Maurice Cherry:

What are the best types of clients that you prefer to work with?

Branden Collins:

All of those clients listed. I don’t think I’ve listed any of my bad clients, now that I think about it. I wasn’t even intentional. I think I just did that. But all of those clients were great clients. I think that the best clients are the ones who see you for who you are and sort of are excited about just, like, applying your capability and letting you do your thing. For the most part, they essentially hire you to do what they hired you to do, right? They let you do what they hired you to do. They are collaborative, and those are the clients that I really appreciate. It doesn’t mean that the work is without criticism and critique. I think the best clients also give good feedback and give a good critique. So it’s a good balance of letting you do your thing and also making sure we achieve the goal together.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, what are some of your plans for The Young Never Sleep in the future? I mean, you mentioned YOO, and I’m looking and seeing that you’ve been working on something called YOO Gen. So I think this is all sort of combined together. What are kind of your plans that you want to achieve through the studio?

Branden Collins:

I’ve been thinking about that a lot. It’s a tricky knot to try to untangle. I think that the way I’m going with things is I think I would love to keep the studio running in its current form as, like, a practice that provides design services and offers a space for creatives to collaborate and express themselves. And as an extension of that, I think I want to push further and further into this world building space, essentially taking all of these stories that The Young Never Sleep has developed over the years and starting to realize them in multimedia formats. So things like gaming, mixed reality gaming, immersive, interactive experiences, simulated environments, physical environments. Yeah, just like, expanding those narratives and making them kind of bigger and more impactive and interactive.

Maurice Cherry:

Now it feels like you’re doing this at a time when I mean, I’d say it’s just at a really good time because of everything that’s going around with AR/VR/mixed reality. There’s, of course, a lot of generative AI. I feel like AI has been put into everything, or it’s trying to be put into everything these days.

Branden Collins:

Right.

Maurice Cherry:

I recently had Carl Bogan on the show, who’s the guy behind Myster Giraffe who does these viral deepfake videos. And we had talked about cultivating media literacy. We talked about critical thinking to help people navigate what’s synthetic media and what’s real media…or authentic media, I should say. I’d love to kind of get more of just your thoughts around all of this — around what’s been occurring with AI, how this feeds into kind of this definition of technoculture that you’ve come up with. I’m giving you the floor to give your thoughts on all that.

Branden Collins:

Okay, cool. Yes.

So technoculture is a term that I started using, which was another one of those things that I later come to find out. It’s an actual term in academia where the idea is to study and understand the relationship between technology and human society and how it sort of evolves over time, how they co-evolve and co-exist together. I’ve taken that same kind of philosophy and practice and kind of expanded it further to just include all of nature and recognizing that nature is in many ways inherently technological.

When you look at evolutionary biology and the behavior of animal cultures, they have cultures, they have social organization, like I talked about before. They make tools, they make technologies and do science experiments of their own. And from that lens, understanding that, again, this technological outcome is just one, essentially, that can exist based on specific context. So the trajectories are really exponential when you look at, okay, what happens when this non-human animal is allowed to continue to evolve, for example, and their technological sort of paradigm starts to expand and evolve on its own. What would that look like, or even from a human perspective, if said indigenous culture was able to thrive instead of being extinguished? What would our technologies look like today? Would they still be gray metal laptops that we stare into all day? Or would it be something totally different? And that’s an exciting thing that is usually taken on by science fiction. But the world we live in is a sci-fi already. So it’s exciting to just think about it that way and also to start putting those things into practice and start actually making these technologies, which is something I’m excited about, this endeavor of technoculture, part examination, part archiving, part practice and research and development.

Underneath that is this vast body of research into the science of information, which has kind of connections to so many different things that helps kind of lay the foundation for that practice. Information science touches everything from quantum physics to the invention and evolution of language to how we organize information in our lives, how information is organized in nature and in art. It’s super interdisciplinary. So I think that’s why I kind of latched onto it. And when we start kind of connecting those things and you start talking about something like artificial intelligence and putting it into context I don’t actually like the term artificial intelligence. I think artificial kind of implies that it’s not natural, which I don’t completely agree with. And intelligence implies that it’s intelligent, which intelligence is always a moving target, just like consciousness. Our idea of it continues to evolve as we learn more. And I think when you start asking questions about what is artificial intelligence? And you put it into the context of anthropology, sociology or evolutionary biology, you start sort of looking a bit deeper and looking at things like capitalism, for example, which I could place under the umbrella of artificial intelligence or white supremacy, which I could put under the umbrella of artificial intelligence or patriarchy, these autonomous systems that operate on agents. You’d be hard pressed to say, like, who has the hand on the wheel in that scenario? Is it the system itself or is it the individual people? And the reality is it’s both. It’s like a mixture of both. So in that context, artificial intelligence more broadly is just about non-human intelligence, quote unquote. So you can look at animal culture and say, how do we define intelligence based on this? Here are obviously conscious beings who don’t have a language like ours, who don’t do things the way that we do, but they are intelligent in their own multifaceted ways. It starts to bring up questions about human intelligence and if certain people are deemed disabled or neurodivergent or so on and so forth, like, is that accurate or do we need to think differently about it in the context of our society? So it just opens up a vast amount of questions. And I’m kind of excited about pursuing the philosophical challenges of it as well as the technical challenges and the ethical challenges. I think they all need to kind of go hand in hand. And it really to me is a provocation to challenge some of the things that we have just accepted as fundamental to our society.

As much as we want to challenge artificial intelligence, we have to, I think, simultaneously continue to challenge our economic paradigm, which is itself a technology, our socioeconomic paradigms, our political paradigms, which are also technologies. So, yeah, it’s an exciting kind of territory, and to me, it’s all connected. So it’s worth questioning all of it and embracing the idea that we have the agency to change it or work with it in a different way.

Maurice Cherry:

Oh, we absolutely do.

Branden Collins:

Yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

I think what I like the most about even what you’ve just described now is you’re taking technology and expanding the definition out of, I guess, what we would consider as computers. I guess that’s kind of the best way to put it, because, I mean, technology really is applying knowledge to achieve a goal in a reproducible way. So, like, the wheel is technology, the printing press is technology, but then food, the telephone, the Internet, et cetera, all of that is technology. And I think certainly the modern definition of tech has been strictly constrained within computers, the Internet, the Web program, like, all that kind of stuff, 100%.

But it’s funny — my mom tells me this sometimes about computers, because I don’t want to say she’s a luddite. I don’t want to put it in such harsh terms, but she’s pretty anti-computer. It took a long time for her to get a cell phone, she doesn’t have a computer at home, and was pretty anti-computer for a while. And she would often tell me humans taught rocks how to think, and we put them in a box and then lost our minds, which is a really kind of an abstract way to think about it, but then you think about the chips and all that stuff is rocks. That’s true. But, yeah, this is all interconnected. Like, none of this stuff is happening within a vacuum.

I think we even see now, just even talking about AI and VR and things like that, these are being applied as layers onto our current reality in ways that kind of make sense and kind of don’t. I think there are still particularly with a lot of AI stuff, there’s infinite possibilities and zero guardrails. There’s no kind of real I don’t want to say legislation, but there’s no sort of guardrails or ethics behind some of this stuff. I think individual entities are putting ethics behind it, behind the work that they do. But now the technology exists and is commonplace enough for you to spoof someone’s entire digital identity 100%. And it’s like, well, what happens in those cases? When that happens, it’s one thing to have identity theft, but then someone has also taken your face and your voice and is able to reproduce things that you could say that sound like you, and it’s like, well, it sounds like Black Mirror. It sounds like science fiction, like you said. But it’s now this is all these are all things which can happen right as this podcast is playing right now.

Branden Collins:

Absolutely, yeah. And I think I mean, even as you described it, I’m working on a story called “Beloved”, which is based on Toni Morrison’s book. And I started thinking about this after watching an interview of hers where she describes the mother taking her infant’s life in order to prevent it from being enslaved. And that story primarily is about artificial intelligence and the ethics of AI from the vantage point of that narrative. Because even as we’re talking, what you just described, someone taking your identity and taking your face and using it to say things that you wouldn’t say or make a caricature of you, these are things that we already have experienced, especially as marginalized people, especially as Black folk. When you talk about enslavement chattel slavery, the identity destruction and reconstruction that had to happen through that process over generations, hundreds and hundreds of years, when you talk about minstrelsy and Blackface and things like cultural appropriation, the artificial intelligence, quote unquote, of white supremacy has already kind of rendered this sci-fi experience of being Black.

One of the great ways to think about AI ethics is to look at the already lived experience of people like indigenous folks and Black folks and queer LGBTQIA people. And really, it’s a mirror of the potential destructive outcomes of a technology like this that is already, as we know, very much embedded with these biases. And it’s also a mirror of some of the potential beauty that can come from that when we have the agency to affect those systems. Because it’s always an evolutionary process. There’s always going to be a tie that comes in and a tie that goes out. Technology is always going to be used in nefarious ways, for the most part. Like you said, the guardrails are off, the cat’s out of the bag, Pandora’s box is open. And, yeah, my mom says to do your best. I think that’s kind of like, the task at hand, is to try to do our best with the information that we have, but we got to do it for sure.

Maurice Cherry:

And now technoculture, the definition of technoculture that you have is the framework for something else that you’ve been constructing called Communion. Can you talk about that?

Branden Collins:

Yeah. So after I left Snap, after downloading all of the information from spending four years there and all of the stuff that I was doing on the side and my own research since, at least I think the seeds of Communion have already been there. But at least since 2015, I did a show in Oakland called “Another World Is Possible: Race and Gender in the Age of Transhumanism.” And that’s, I think, when I started the seed of this framework.

But certainly after I left Snap, I kind of went to a group of thought leaders who are also mutual friends, collaborators, with this idea for a platform that was essentially a new kind of like information Internet and manufacturing infrastructure. And after presenting that and sort of taking a step back and thinking about it more deeply, I realized I needed to do a bit more work on this idea. So I started breaking it out into different frameworks.

So at the base, so to speak, information science kind of sets the stage for technoculture, which is the space that we sort of explore and sort of facilitate the production of different technologies through this kind of philosophical shift and then through that process, Communion, I think of as frameworks.

So one of them, for example, is a legal ethical framework for alternate realities. So when we talk about things like AI, like deep fakes, like AR/VR…this framework specifically is geared around how do you deal with illegal ethical challenges in virtual reality. I’ve read stories about people getting assaulted, like assaulted by groups of people in VR and different types of violence in VR. I’ve read stories about augmented reality and sort of being able to manipulate people’s reality and their perceptions using things like deep fakes. And it’s a vast, uncharted, very complex territory that I don’t think a lot of our institutionalized government authorities really have a sense of how to navigate. To me, it is a very much a grassroots effort that needs to take place. So that’s one of them. I have several others.

One of them is about full systems health and wellness; a framework for that. So thinking about the different dimensions of a person’s individual, collective and sort of global experience of health and what would it look like to actually make a healthcare infrastructure that takes into account how we relate to technologies. How? You use the Internet, how you use social media, the food you eat, your cultural context, what your background is as Black people understanding how deeply systemic injustice is to our individual health and the health of the planet. Kind of connecting all these things together and going like, okay, every person lives essentially in their own reality. And based on that, every single person needs to have a different sort of approach to health that’s specific to them. But it also can be navigated as something that’s beneficial for the collective. So that’s another one. There are several others that kind of, like, are all about different subjects. So communion is just a series of frameworks that could then be applied to a person’s individual life or as a body of research for institutions and things like that. That’s kind of the long and short of that.

Maurice Cherry:

To me, all of this sounds utterly fascinating.

Right around this time last year, I was working at this startup, I was working at this French-based startup and they wanted to make a magazine dealing with product communities. We had already published, or we already had two issues that we had done. It was a quarterly magazine called Gravity. And for the third issue, we wanted to do something on Web3. They had the idea come out like, “yeah, we want to do something on Web3.” This came directly from the CEO because I think he wanted to try to pivot the company into Web3 stuff. And people at work were like, “no, if the issue is going to be about Web3, I don’t want to write about it. I don’t want to have anything to do with it.” And I’m the editor-in-chief of the magazine, so I was like, “okay, fine. We can find some people to write about it. This magazine doesn’t live or die if you don’t decide to do it; it’s totally okay.”

And so we brought in a Web3 ethicist to serve as our guest editor for the magazine. And we put together a slate of different topics and articles. And some of it was on the things that you just mentioned on what does digital identity theft look like, what does safety look like in the metaverse, that sort of thing. And this was like a year ago. Unfortunately, I got laid off along with our entire team, and so they completely not only killed the issue, but killed the magazine as well. So unfortunately, none of that stuff will ever see the light of day.

But I do find it all super fascinating because these are going to be the realities that we have to contend with in a few years. And I’ve been around on the web since the 90s, so I see also the parallels between stuff happening now and stuff that happened back when the Internet for sure started to become a thing. Like, the concept of real estate in the metaverse, for example, was very similar to what I remember the million dollar home page being like the Million Dollar Homepage was like this website where people bought ad space. Like they could buy like an 88×31 pixel web space and put whatever message or something on the very similar to, I guess, like r/place on Reddit. Like, something like that, but people paid for it. And then like, the concept of real estate in the metaverse where people are paying tens of thousands of dollars to have a plot of land — quote unquote, “land” — in a Metaverse that not only is not interoperable, but kind of doesn’t exist really. I literally was in a conference…not last year, this was 2021. It was a metaverse conference in the metaverse, and someone during one of the talks had bought like an acre of land for $10,000. And I’m like, “Why? What are you going to put there?” I don’t understand what that even means. You’re buying $10,000 worth of space in the metaverse. I guess you could put a digital house there and show off your NFTs. Remember when NFTs were a thing? All of this stuff is changing in such a rapid fashion, and then of course, culture is trying to catch up with how this is all happening. And so it just reminds me of the time back when the Internet was first becoming a thing and people were trying to stake their claim with websites. Companies were really skittish about if they should even put their business online. It’s all, I think, connected in that way. Like, I’m seeing those patterns re-emerge.

Branden Collins:

Absolutely. There’s this quote that “history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes,” which I like a lot. And, yeah, you’re absolutely right. There was stuff like GeoCities back in the day, which was very similar to that. The Sims in the 90s, which is obviously the metaverse. A lot of old games that even I used to play, like Age of Empires was a game that I used to play way back when on the computer, where you basically build your own civilization from scratch. There’s all of these things that, yeah, we had and that are kind of reemerging in this new environment. And, yeah, there’s so much of it, and it’s happening so fast that I certainly don’t think aging somewhat archaic government institutions can really navigate this territory. But I think that the people who have had experience in that space, the gamers and creative technologists and creative people, artists do, and I think it’s, again, an opportunity to challenge the institutions that we sort of just accept.

I think your sort of description of the digital real estate is a great example because, yeah, it’s technically not real, but it is real, and it starts to challenge our idea of what’s real or not, which has pros and cons. But when you think about a concept like Manifest Destiny — how the country was conquered and these false deeds that allow people to take land and property and kind of a fabricated legality behind it — it’s pretty fascinating. Because to me, in that context, it’s like, okay, there’s like, a subtle difference between somebody holding a piece of paper that, because of their authority, makes them the owner of a thing that they can just then take from you. And this other thing, which is digital, which is kind of two sides of the same coin, and the physicality of it is sort of sometimes just an inconvenient kind of truth about the way we experience the world. But, yeah, I mean, that’s what I get excited about information science about is when you get into, like, quantum physics and all of the really weird stuff about reality intangibility, but it’s all connected. And I think, yeah, it’s fascinating. I think people should be kind of cautiously enthusiastic about this whole space, this whole kind of new digital environment. And it’s always healthy, I think, to just look at history for examples of how things can go right and how things can go wrong.

Maurice Cherry:

Absolutely. I’m actually taking that approach now as it relates to social media.

So, like, we’re recording this now at a time when Twitter just became X, like, I don’t know, a couple of days ago or something like that, right? And people had already been having kind of, you know, reservations about the platform ever since the new owner took ownership and how things have changed. And so of course, since then, a number of different Twitter-like clones have sort of popped up or they’ve made themselves known, I’ll say I won’t say they just popped up, but like, there’s Spoutible, there’s spill, there’s posts, there’s mastodon has been around for a long time. There’s blue sky. Instagram came out of left field with threads. And people are trying to determine like, okay, well, where should I go next? Well, should I go over here to Threads? Well, Threads does this, okay, well let me go over to Blue Sky. Well, Blue Sky is like this, and can I get an invite? And it reminds me of 2006, 2007 all over again. One with the invites, that’s the first thing, right? But then two with also when Twitter was around, then there were a number of clones that had popped up that was trying to take its market space. Eventually there was Pounce, there was Plurk, there was Jaiku, there was Yammer, there might have been a couple of others. And within a year’s time, most of those didn’t exist anymore. They either got acquired by a company and shut down or they just couldn’t hack it, essentially, or they’ve pivoted to another market. Like, Plurk is huge in Taiwan. I don’t think anybody in the US really still uses anymore. So I’ve been cautiously looking at like, oh, well, do I even want to be on these other platforms? Because even with Twitter, I don’t share a bunch of shit on Twitter now anyway. And I don’t think me migrating my presence to another platform is going to necessarily change that. Like people will say, oh, I’m on Threads, and oh, this reminds me of how social media used to be. And I’m like, look, if Elon Musk is the problem, mark Zuckerberg is not the like, let’s step back here and put this into some context. But also just thinking of like, I remember the Internet when social media was not a thing and it was fun.

Branden Collins:

It was, yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

So even now, especially as I get older, I’m like, I don’t even want to really have a social media presence. Like as a publisher of Revision Path, I have to think, “oh, well, where do I want the show to be so people can find out about it?” So then I have to have those conversations with myself and my team about what even makes sense. But personally, I could give all of this up tomorrow and be fine.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, I feel that it’s kind of like a gold rush, like speculators, like running to whatever the hot town is at the time and trying to stake your claim. So, yeah, it’s definitely spot on and that would be a good archive, actually, is actually all of the platforms that have come and gone in relation to all this stuff. I think it would be like a humbling thing to see just how many of them have just come and gone and only a small few rise to the top because that’s just like the nature of the thing. So as we try to rush from one thing to the next, it’s just like it might be better to just take a minute to think about what it is we’re actually trying to do and get from these platforms. And is there a way to kind of re-claim that sovereignty and autonomy for ourselves? That’s something that I’m really interested in and trying to put into practice more regularly.

Maurice Cherry:

It’s like, what’s the connection? Because one thing that people have been talking about, and I promise we’ll pull this back into talking about Yoo, but one thing with people trying to go to these other platforms is then trying to recreate the social graph that they had on Twitter. So they’re like, oh well, if you’re going to be here, then I need to be here, and where are my people that are also on this? And it’s like, well, you can’t take your network with you in that way. There’s your offline real world network that always stays with you. And then there’s this sort of Ursat, cultivated network that’s been done through this social media platform that now you have to try to recreate and reconstruct on some other platform that may not even exist within a year’s time.

Branden Collins:

Exactly.

Maurice Cherry:

And also with the old platform X, Twitter, whatever it is, if you’ve had people muted or blocked or things of that nature, now that you’ve moved to this new platform, those restrictions no longer really apply. So they can try to harass you somewhere else. They can try to befriend you somewhere else and you’re like, “no, I don’t talk to you on Twitter; that means I don’t talk to you anywhere.” It’s so weird. It’s so, like, it’s very complex, which makes me want to just give it all up. I’m like, this is…y’all can have it.

Branden Collins:

It’s not that serious. Yeah, it gets overwhelming and it’s especially challenging, I think, for people who find a lot of value in kind of distributing their identity or having new identities online that they can’t have in quote unquote, real life, because that is something that’s very beneficial for a lot of people. I would include myself in a part of that. And especially, I think, like, younger generations and queer folks is, like, not generally, but a lot of people find a lot of value in being able to assume a different identity and being able to sort of go to a new town, so to speak, where nobody knows your name, and being able to recreate yourself. And there’s a lot of challenges behind that with all these new platforms, with legacy platforms that fade away.

One of the things that I’m really concerned about with Twitter, and just like these social platforms in general is something called link rot. Link rot. This idea that, I think, we forget that the Internet is very ephemeral and that if a server goes down, if people aren’t there to maintain it, that all of your tweets can just go away or all of the things you’ve saved in Google Drive or whatever other cloud service or all the things you posted on Facebook can just go away one day. There’s just this wealth of knowledge on a platform like Twitter that could be lost not only with the name change, but with the infrastructural changes that are there. And it’s the equivalent of burning down the Library of Alexandria with all of these connections and conversations and this sort of archive of this moment in time that we will never see again. It’s a little like concerning, not a little concerning. It’s pretty like it worries me a bit.

Maurice Cherry:

You know, I did a talk — oh my God, this is maybe two or three years ago — I did a talk called “Content is Subject to Change” about this very same thing; about how the Internet is not an archive. I know there is the Internet Archive, but that is a small nonprofit. It’s an institution, yeah, that one can’t archive the full web because there are certain restrictions around the type of content about the location of said content. It’s not even available in some countries. So you can’t archive the full web, but also just sort of talking about with the advent of user-generated content through social media, Web 2.0, et cetera. We are putting so much stuff on the Internet without thinking about how it is being stored, if it’s being stored, like news articles. Try to find a news article from ten years ago and see if all the images still work, or see if all the links, you know, link rot, like you mentioned, still works. And like, it makes it hard for history purposes, for archiving, et cetera. Yeah, the Internet is very ephemeral in that aspect.

Branden Collins:

Yeah. And that’s like one of the sort of ambitions of you. The platform that I’m working on with Ami is to at least kind of, in our own way, create these tools and allow people to create their own tools where they can create a living archive of at least themselves, of at least their digital self, and try to connect it to their physical self in a way that is ownable, that has sovereignty for them. And reclaiming all that data, reclaiming all of the information that we’ve dumped online and making sure that you are able to house it somewhere that you can access and not lose it. Because all of that stuff is hugely, hugely important. People’s digital stuff is…I don’t think we think about this consciously all the time. We kind of take it for granted. But it’s not until you lose it, it’s not until the house burns down with all your stuff in it that you’re like, “oh man, right. I probably should have saved that somewhere or made a copy of it.

Maurice Cherry:

Yep. Put it on a physical hard drive or something.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, right, absolutely.

Maurice Cherry:

Even as you mentioned that, that kind of reminded me about sort of one of the restrictions of Threads, like when people were sort of looking at different platforms to jump to and sort of the notion you mentioned about people being able to assume different identities on different platforms. Like there’s who you are, maybe in the real world, but then on the internet you can be a different person or a different identity or something like that. And I know there were people like adult industry professionals, sex workers, porn stars, et cetera, who said that they had joined Threads. And Threads, because it’s Instagram and Instagram is owned by Facebook, now links them, their stage name, to their real person identity. And that if you try to delete Threads, then now you delete Instagram. So now it’s like tying together these things. You didn’t ask to be tied together, but because you’ve opted into the platform and no one reads the long ass end user licensing agreements or the terms of service, but now that you’ve opted into it, it’s like this is what you signed on for.

Branden Collins:

Yeah. And you can’t go back and it’s super manipulative, I think, and nefarious and not by accident. And yeah, that’s in and of itself a huge conversation about sex work online and sort of platform and surveillance capitalism. And I have friends who are sex workers. I kind of consider myself to be in that territory, at least online anyway. I have an OnlyFans. It’s a huge issue. Not only the deplatforming, the silencing, all of that stuff, which I think is hugely messed up because in a lot of ways these platforms make a lot of money from the revenue that’s generated by these users, these citizens of their platforms, while at the same time silencing them, even sometimes encouraging violence and disrespect towards them. There aren’t a lot of really safe equitable spaces for sex workers and marginalized folks online and I’m excited about seeing more of that. I think the metaverse — not Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse — but the Metaverse more broadly and gaming and kind of world building environments is at least one space that I feel excited about the opportunity for those things to open up more and just people like making their own platforms. I think back to the era of blogging, like hosting your own platform yourself. I think that’s exciting and I think we’ll probably see people do more of that for sure because I think people are getting really fatigued with all of this stuff.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah, no, absolutely. I feel like we could have a whole other podcast episode just about what we talked about with the advent of technology through porn and sex work. Like a lot of technological innovation, especially like when we talked about synthetic media and things like that. Unfortunately it’s come because of that, that innovation has spurred technological innovation. But we’ve spent a lot of time talking about this. I want to make sure that this interview is also about you. So let’s switch gears here, learn more about you. Now, you’re originally from Cleveland, is that right?

Branden Collins:

That’s right. Yeah. I was born and raised there.

I lived there until I was about 13, and then I moved around in the south quite a bit. I went to high school in Douglasville, Georgia, for about a year. I went to high school in Montgomery, Alabama. That’s actually where I graduated high school. And I ended up going to SCAD in Savannah for two years. I’m a college dropout.

I loved my time at SCAD, especially the people. And just like, that city, I think, is beautiful. Yeah. I was a 3D animation major and an illustration minor. I thought I wanted to work at Pixar at that time. That was my first kind of venture into the 3D space, at least using computers. And I think it kind of stuck with me even though I hadn’t revisited it until more recently. A lot of the ideas, understanding the potential of it definitely stuck with me. I’ve always been interested in science and technology. I would have just as soon went into robotics or something like when I was a kid. I wanted to be an aeronautical engineer. I wanted to be a paleontologist. I had all these kind of aspirations. I think that’s true for a lot of creative people.

I think something that I realized about kind of the world we live in is the unfortunate sort of reality of this kind of reductionist approach to so many things, where you have to choose one thing to be when that’s not really how the world works. And that was definitely a big part of starting the studio, was that using it as a vehicle to do whatever I wanted to do. And I think people feel inspired to rally around that. So, yeah, that’s been the journey with that.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, after SCAD, I saw that you kind of worked for a while as a designer. You worked for Radio One for a while, but then you also started collaborating with other creatives. You started this collective called The Big Up. Tell me about that, because it sounds like that’s kind of been the basis for what you do now through The Young Never Sleep.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, 100%. At SCAD, I met a group of really dynamic people; Bittany Bosco being one of them. Alex Goose, Danny Swain, Lloyd Harold, a number of other amazing people. We all kind of went our separate ways, but stayed in touch. And then after going back to Montgomery for a little bit, I went back to Atlanta. And at that time, I was just doing just like, freelance graphic design, doing club flyers and making people’s album artwork. Fadia Kader was one of the people who —

Maurice Cherry:

Oh, yeah, I know Fadia.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, she’s awesome. She’s one of the people who kind of helped jumpstart my design career. And yeah, I started working with Brittany and Alex Goose and Danny really closely. I’ve done album artwork for Danny. I did some vocals on one of his albums. I’ve done album artwork for Brittany and her show, kind of posters and things like that.

So, yeah, we started the collective The Big Up, and it was essentially like part label, part creative agency where we just wanted to do everything in house. We made the music, we made the art for the music. We did the set design. We did everything. And that was definitely one of the things that I think transitioned me from being an artist to being more of a design thinker, and certainly like a systems design thinker. And then, yeah, I worked for Hot 107.9 for a little while. I actually lived there for a short period of time. I had an experience with houselessness for a brief period of time, and I actually lived at Hot 107.9 making designs for Birthday Bash. And I would just stay in the studio when everybody left and just sleep there. I’d always been interested in computers, like, I had a computer at home. It was really old, and I’d play games on it and do stuff I wasn’t supposed to be doing. But, yeah, at Hot 107.9, just being there for that time, I was like, obsessively going through blogs. This is the time of LimeWire and all of that stuff. And just torrents and downloading just twenty albums at a time and just listening to Japanese prog rock and just cosmic jazz and all this crazy stuff from everywhere. It was incredible. And I remember I saved all this music on a hard drive, and I ended up losing that hard drive. So I think maybe that might be like some trauma that made me want to archive. There might be some trauma there. I’m like, I never want to lose anything ever again.

Maurice Cherry:

Listen, I have a hard drive here now at the house that’s got a ton of music on it that I can’t access for some reason. And I’m like, one day I’m going to crack it and get all my music back that’s on there. So I feel you there.

Branden Collins:

The world needs that.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah.

Branden Collins:

But yeah, The Big Up. Yeah, that was definitely one of the things that was kind of seeded The Young Never Sleep and what was possible through that. You know, it’s been a journey. I still am connected to Bosco. The last time we worked together was a project with Spectacles. It was one of my favorite projects I’ve worked on there, actually. And one of the things that kind of set the trajectory for where I’m headed now with my work. We did her single July 4th or 4th of July. We created this video, which was essentially a concept for a music video game in mixed reality. Yeah, it was a really cool project where we used the AR lenses from a lot of Lens Studio creators, and I made toys based on the characters in a video and made several AR experiences. A really great 360 project. It’s a really cool one.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Brittany was actually on our 2019 honoree list for 28 Days of the Web. Yeah. We have, like, a sister site where, for Black History Month for February, we profile 14 men, 14 women that are doing really interesting, great digital stuff online, whether that’s design, tech, et cetera. That’s something I’ve done for the past ten years.

I’ve been debating on stopping it. This is my first time saying this publicly, by the way, because I’ve done it for ten years. I’m like, ten is a good round number. I don’t know if I want to do it again for next year, mainly because — and I didn’t think this would be the case, but I don’t know, maybe it’s kind of tied into our conversation — some people just don’t want that presence online anymore. They’re contacting us and being like, “yeah, could you take down the profile that you did?” They thanked me when it was up, but then now that it’s up, they’re like, “yeah, can you get rid of that?”

Branden Collins:

Okay.

Maurice Cherry:

Because I’m like…yeah. So I don’t know.

Branden Collins:

All right.

Maurice Cherry:

I’m on the fence about doing it again for 2024, but we’ve done it since 2014, so it’s been ten years. So I don’t know. Maybe we will, maybe we won’t. I don’t know.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, okay. I feel that it’s like that. Things change.

Maurice Cherry:

Yeah. Now, when you look back, art, some of the big places you’ve worked, like, you mentioned, Snap, you were there for four years in L.A. You’ve also been at Cartoon Network for four years here in Atlanta. When you look back collectively at those experiences, what do you still carry with you from there?

Branden Collins:

My experience working at those places, for me was like, my school. I apply myself in these careers as me, like, learning by doing.

At Cartoon Network, I got a deep appreciation for how to apply artistic thinking to design. There’s a fine line between art and design, and sometimes it’s nonexistent. And I think at Cartoon Network, I got an appreciation for how art and design can be the same thing. I got an appreciation for systems thinking again. I tell people we essentially did everything except make the cartoons. So we were, you know, making interstitials, making commercials, print ads, web ads. We did immersive experiences for, you know, we built a booth. I helped make a gigantic inflatable obstacle course in the Bahamas. It was like, so much work that got done making premium clothes and all kinds of things. Working for Cartoon [Network] and Adult Swim, you get a real sense of all of the touch points that have to happen in order to make a project successful or a product launch successful.

So I got a real sense of that there, and I have to thank people like Jacob Escobedo, who got me the job, and for him believing in me not having a degree, just seeing my work. He literally just asked me to bring in a sketchbook. He’d look through my sketchbook and hire me based on that, which I really appreciate him for that. And then Candice House, I have to say, is someone who sharpened my eye for detail and quality. She, as an art director, you know, is exceptional, and is someone who I think just is exemplary of the Cartoon Network brand. So I got that there, and then I left after four years. I graduated, so to speak, and then I freelanced for a while with that knowledge, working on projects for Dolby and HBO and several other kind of higher profile brands, which it’s great for me, I think, to go back and forth to have this kind of independent, self-starting thing, but also to be within the institution. Because I think you just learn different things from those experiences.

And then after a while, I got the job at Snap by working with Larissa Haggio, who’s a fashion designer in L.A. Andrew McPhee, her partner, got me introduced to Snap and the Spectacles team. And at Spectacles, I was there for four years. Another kind of graduate situation. I think the big takeaway there was how hard it is to make tech. I got a much deeper appreciation for the things that I think a lot of us take for granted. When our laptop is on the fritz or the GPS doesn’t work perfectly, it’s easy for us to complain. But I got a real reverence for the complexity and challenge of trying to make a piece of hardware and a piece of software and also trying to get it out into the market in a way that people will embrace it. It’s a very, very hard, complex thing to do. And I was there through four launches, four product launches, doing a little bit of everything with the brand and even influencing the product as well. I got a lot of experience with working with product teams and trying to set the vision and design a product. So I think those two kind of big pillars, Cartoon Network and Snap Spectacles together, I think, alongside my independent work, really set the stage for where I’m headed in the future.

Maurice Cherry:

I love that you kind of referred to both of those experiences as, like, graduation, for sure, because jobs do when we’re working at these places. They do teach us things. It’s not just kind of a particular tenure of employment, like some of the work that you did just looking back, like with Cartoon Network and Adult Swim, when I said before that I’ve seen your work before, I’ve seen your work before I knew it was you. The Adult Swim singles covers and stuff, some of the best design I’ve seen. And I’m like, this is coming out of Atlanta, and I mean, during a time when honestly, and I would probably still maybe say this even now, people don’t look at Atlanta as a design city.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, 100%.

Maurice Cherry:

I think certainly they look at us for entertainment. They look at just the creativity that comes here out of, like, the music scene. But I can tell you, from doing a show for ten years, people do not look at Atlanta for design at all.

Branden Collins:

You’re right.

Maurice Cherry:

Tech, they’ve started to because of the startup scene, but, like, design? Please.

Branden Collins:

Right.

Maurice Cherry:

Do not get me started about some of the design arguments and conversations I’ve had locally trying to help put Atlanta on the map about stuff. It’s just like…man, I don’t know.

Branden Collins:

Yeah, it’s such a shame. It does such a disservice to the culture to not acknowledge that. A lot of us been doing it for a long time. And I appreciate that you continue to advocate. I think it’s true. I’m passionate and committed to Atlanta. I’m not like, an Atlanta loyalist. Having lived other places, other places are really amazing as well. But I think it definitely does a disservice to the city to not acknowledge the design and art and tech and entertainment and all of those things that are very much present here. What I really see is just like an opportunity, actually to continue to foster the kinds of platforms that need to be unique to this city. I think that’s one thing that we’re tasked with, or anyone who’s creative here, is like, if you’re a person who’s committed to this city and committed to seeing it continue to improve, the reference points don’t need to be anywhere else but this place and the people who live here. And that’s it. It has its own thing, and that’s all it kind of needs to be.

Maurice Cherry:

Absolutely.

Branden Collins:

Yeah.

Maurice Cherry:

What do you think it means to be a creative person today?

Branden Collins:

I think it’s like a common thread for me to see creativity as a way of self-affirmation on a really, really deep level. I think it’s a way to self reflect and to obviously connect with other people. I think from that place, when I think about something like a term that’s maybe on the verge of being overused now, this term “world building”, even before coming across the word, I think that our task of world building. As creative people, whether that is world building through writing a novel or doing photo shoots or making video games or creating a space where people can come and enjoy themselves or receive healing. I think world building as a practice is kind of our premier task.

The way that I sort of contextualize this for people is like me as a young black queer kid growing up, the world builders that I knew were my grandmother and my mother and my aunt who, when I stepped into their homes, I was confronted by all of this beauty. Black intellect. My grandmother had libraries about Black people, about Africa and Black dolls, and the walls were painted colorfully and bright, and my aunt’s home is just…you step into this world that’s, like, self-affirming, and it really just nourishes you. And it builds you back up to step out into the world, into a world that is not always so affirming. And to me, I think that’s the premier, I think, task is to continue to build that world and to do it together and bring it all together because we have the power to shape the trajectory of the world we live in and change the outcomes just by making it by making it real. And I’m excited about that. And I think the depth of that pursuit means challenging institutions continuously. Challenging how education is disseminated, challenging how social systems are disseminated, challenging authority kind of at all levels. Yeah. And just, like, affirming ourselves and even making something a little bit better is, I think, a win a victory.

Maurice Cherry:

In recent years, what would you say is one of the biggest lessons that you’ve learned about yourself?

Branden Collins:

I think it’s been humbling and exciting to put my own creative pursuit within the context of this sort of deep time. Being conscious of that. It’s opened a huge window for me as a part of my research. I recognize that, oh, wait…the sort of visual and sonic and conceptual themes that I am tapping into through my work all exist on a continuum and in a network of all these other minds and ideas and sort of questions. And once I step back and sort of look at that in that context, you start to get a different picture. Like, a different picture emerges of, like, okay, we’re all having this collective conversation. Like, touching on this idea of artificial intelligence again, is like this sort of collective consciousness that’s present through history, through this deep time of nature and all these things tracing that thread, it’s sort of simultaneously reduced who I am and also expanded it in ways that are just, like, reinvigorating. And it’s pretty profound to me, it’s felt profound.

Maurice Cherry:

Now, this might be a big question kind of given, I think, the general kind of trajectory of where your work is, but what kind of work do you want to be doing within the next five years? What’s the next chapter look like for you?

Branden Collins:

It’s a little tricky because there’s kind of a duality. I want to be more accepting of where I am, whatever that circumstance is, and in many ways just live small, live in a more small way on a personal level. But at the same time, I want to show people what’s really tangibly possible through the practice of world building and self kind of recreation. We’re living in this sci-fi world, and we watch really entertaining shows, you know, Black Mirror and Marvel movies or whatever, all these things that are really cool, like narratives. But I think I want to kind of take storytelling a little further. I really want to make tangible extensions of myself or of other people or worlds that people can really step into, make that collectively with other creatives.

I think the practice of world building…I take it really seriously because I know that a world has been built for me to live in. I always use Frank Ocean’s line — “living in an idea from another man’s mind.” I think that perfectly encapsulates our current circumstance. That somebody had an idea that one person of a color was less than another person, and now we live inside that idea. And a lot of the things that we now have to contend with as social institutions were just somebody’s idea that they wrote in a book, just proselytized to their group of friends. And then it became a global institution that has industries and infrastructure and military might to support it. And that to me is like fascinating that that can happen from just the seed of an idea.

So the creative pursuit, I think, is not to be underestimated that you as a person who has a concept or has an idea, you couldn’t begin to comprehend what that could look like in ten years, 100 years, 1000 years. And I kind of want to show people that that when we say another world is possible, that no, actually, yeah, the world like, for real, and that it is. And it’s not only possible, but it’s probable and practical as well. That’s what I want to do.

Maurice Cherry:

Well, just to kind of wrap things up here. And I know we’ve covered a lot, but just to wrap things up, where can our audience find out more information about you, about your work? Where can they follow you online?

Branden Collins:

So you can go to @theyoungneversleep on Instagram or theyoungneversleep[.com] online. My Instagram has a Linktree with a bunch of other links as well that people can jump into. Those are the best places to find me.

Maurice Cherry:

All right, sounds good. Branden Collins. Wow. Wow. This conversation was so good. I think one it was just, I mean, first of all, thank you again for coming on the show. But the stuff that you’re covering are the things that I think as designers, as creatives, as technologists, we need to be thinking about because we’re probably best equipped to actually help to shape that future of what things can look like through 100% technology, through visuals, et cetera. And I just thank you for helping to put these ideas out there. Thank you for the work that you’re doing. Hopefully one day we’ll have rum together at El Malo for sure. But yeah, again, thank you so much for coming on the show, man. I appreciate it.

Branden Collins:

Thank you very much. Have a good one.