The advent of photography and film arose from a desire to capture impressions of our lives and the world we inhabit, giving us the power to record and share our unique perspectives with the world. Developing mechanical functions for photographic exposure meant camera manufacturers would experiment with aperture size and settings to enable control over how much light the iris allows to pass through the lens, resulting in the overall brightness of the image. Early photography and film was developed by and tested on people with light skin; hence image capture technology only accommodates those with a similarly light complexion, leaving anyone with a skin tone outside of that very limited dynamic range at the mercy of technological limitations like less control, comfort, and quality for their images.

In recent years the ability to capture and control our own image has been increasingly acknowledged as an important form of personal empowerment, enabling us to control and curate our public image and perception. It’s no question selfies can empower, but what if the technology used to take them isn’t designed with your image in mind?

Shirley Cards and Colourism

“Here’s a Look at How Color Film was Originally Biased Toward White People” – https://petapixel.com/2015/09/19/heres-a-look-at-how-color-film-was-originally-biased-toward-white-people/

For many, colourism conjures up the antiquated “brown paper bag test”, an antebellum era symbol used to determine whether a slave would work in the house or the fields; if their skin was lighter than a paper bag, then they were deemed fit to work indoors. This class criteria stems from white supremacist ideals that recognize and reward light skinned black people for possessing fairer skin, and thus receiving certain privileges or a higher social standing than their darker counterparts. Centuries-long beauty standards declaring fair skin as more desirable and thus more deserving of praise influenced early photographic and commercial representations of beauty, focusing exclusively on white and light-skinned subjects.

In the mid-1950’s Kodak introduced a discerning skin test of their own, based on the pale complexion of Kodak employee Shirley — namesake of the Shirley Card — the model for standardized exposure for millions of Kodak customers used exclusively by the company and all major developers until the 1990s. Those who failed to meet the standards set by her impossibly pale visage discovered themselves in underexposed, even unrecognizable states when their film returned from the lab. BuzzFeed contributor Syreeta McFadden describes an all-too-familiar experience seeing photos of herself as a child in her article detailing her experiences as a black photographer:

“The clothes were OK — the bright blue vest over a striped blue shirt underneath. The updo wasn’t the camera’s fault. But my eyes looked like sunken holes in a small brown face, and my pupils were invisible.

‘I don’t even look like me.’”

Demands for improvement and accountability from Kodak’s biased standard of film development only began when furniture and chocolate manufacturers sent in complaints about Kodak’s limited ability to capture dark colours. As former head of Kodak Camera Research Studios Earl Kage explains in Ronald Hall’s book The Melanin Millennium: Skin Color as 21st Century International Discourse:

“Manufacturers of furniture were having a good deal of difficulty in demonstrating the subtle differences of certain woods[…] This was also about the same time that we got some interesting observations from chocolate manufacturers who, in displaying Whitman’s chocolate, the subtle variations between the dark and bittersweet and milk chocolates weren’t as discernable.”

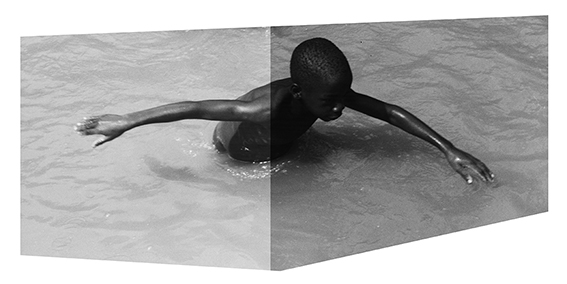

Kodak’s remedy for the negative PR was to roll out new film stock with the improved ability to photograph dark colours, which Kodak jokingly boasted could capture the “details of a dark horse in low light.” Accommodating their equestrian customer base managed to find its way into their list of technical priorities; however, dark-skinned people never seemed to factor into their product design. In 2012, visual artists Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin developed a project named after the company joke exploring Kodak’s history of racist filmstock, photographing a number of subjects with their film and exposing racial bias through their collection.

Strip Test 7, To Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light, 2012

Homogeneity Harms Innovation

Shirley’s status as a decades long symbol of “normal” skin tone and exposure is exemplary of how development and design are shaped by the implicit biases and perspectives of the designers who program and develop technology. Numbers for diversity in tech show that an overwhelming percentage of employees for the largest and most influential tech companies in the world are white and male, meaning when it comes time to develop globally-shipped products, they’re stuck thinking in the scope of themselves as their consumer base — a shortcoming reinforced by media representations placing white men at the default majority. Just as Shirley’s inclusion was dictated by both the commercial appeal of her skin colour and convenient employment at Kodak, companies often use their own employees as their sole focus groups, leaving crucial demographics out of UX and product design considerations.

Without a diverse workforce or quality assurance team to ensure more than one target group is considered during development, underrepresented consumers only interact with a product after it’s too late and has already hit the shelves. And when it comes to design, diversity in the development and testing phase are key to inclusion and accessibility, lest designer’s implicit biases be left to shape their creative methodologies.

Persistent Patterns

“The Quiet Racism of Instagram Filters” – https://www.racked.com/2015/7/7/8906343/instagram-racism

Over the last century, image capture technology has shifted from a professional and hobbyist pursuit to an essential part of digital and social cultures. Hundreds of programs and apps exist to edit, filter and share our photos, but even as personal photography has become essential on a global scale, the tools we use are as unnecessarily limited as some of the earliest photographic tech. Camera and app manufacturers continue to limit their design with a predominantly white userbase in mind, and it has resulted in limiting access to users of colour.

When HP released their MediaSmart webcams boasting facial recognition capabilities, they said they used algorithms that tracked lighting contrasts between different areas of the face for their code. The webcam’s inevitable inability to track dark-skinned users was demonstrated by a black man and his white co-worker, who are shown taking turns entering the frame but only the white coworker is detected. In a more personal and playful attempt to show the difficulty of capturing light and dark skin simultaneously, this couple posted the impossible process of taking a selfie together without one of them being rendered invisible by unaccommodating exposure.

“Racist Camera! No, I did not blink… I’m just Asian!” – https://www.flickr.com/photos/jozjozjoz/3529106844/

With over 400 million users worldwide, Instagram is the most popular photo-sharing platform in the world. Yet even with such a large user base, their built-in filters offered to stylize and enhance images show a disturbing inclination to also lighten their subjects beyond recognition.

Beyond the failure to detect diverse shades of skin, some apps’ obvious lack of user testing ignores other crucial differences based on race. Nikon raised eyebrows when their Coolpix S630’s facial recognition software consistently accused Asian users of closing their eyes before a photo was taken. Joz Wang would see the message ‘did someone blink’ appear on the screen before taking a photo, but nobody had.

All of these cases sadly prove a trend of alienating and excluding diverse users from interacting with image capture technology, an issue that could easily be prevented if systemic barriers affecting diversity in tech and biases in product testing were acknowledged.

From Exclusion to Innovation

Working to equalize the built-in bias of the tools we use for work and in everyday life has mostly been led by creatives of colour making strides in cinematic and photographic progress. Where white professors and filmmakers would offer unhelpful, offensive advice like rubbing Vaseline on the skin of darker actors to reflect more light, black and brown directors and photographers have gone straight to the source — the technology — to produce better images.

Bradford Young — cinematographer of Selma and A Most Violent Year — discusses not being afraid to underexpose a subject if it means ‘increasing the richness of the skin tone.’ Filmmakers Steve McQueen and Ava Duvernay have been vocal about Hollywood’s tendency to underexpose black actors or light them so heavily in scenes shared with white actors that they sweat profusely, like Sidney Poitier’s lighting during the filming of In The Heat Of The Night.

Addressing technological deficits designed by social and institutional bias is the first step towards designing more inclusive tech in the future — an issue diverse creators are taking on to change the technical landscape one photo at a time.