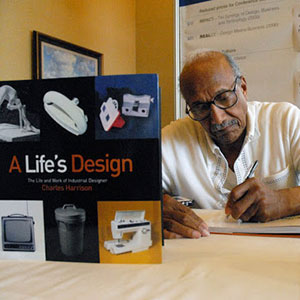

Design is often assumed to be purely about aesthetics; a practice in bringing awareness to an object’s form. Charles Harrison’s work as an industrial designer with Sears brought focus to form as much as function, incorporating practical, life-improving considerations to over 600 products during his career. His ability to consider everyday use into his design resulted in some of the most popular household items still in use today. In 2005, Harrison released his memoir, “A Life’s Design: The Life And Work of Industrial Designer Charles Harrison,” in which he ruminates about his successes throughout his long career creating innovative designs.

Design is often assumed to be purely about aesthetics; a practice in bringing awareness to an object’s form. Charles Harrison’s work as an industrial designer with Sears brought focus to form as much as function, incorporating practical, life-improving considerations to over 600 products during his career. His ability to consider everyday use into his design resulted in some of the most popular household items still in use today. In 2005, Harrison released his memoir, “A Life’s Design: The Life And Work of Industrial Designer Charles Harrison,” in which he ruminates about his successes throughout his long career creating innovative designs.

Despite the universality of his work, Charles Harrison wasn’t widely known outside of the industrial design industry. He began his career as a designer for Sears in 1961, and his focus on practicality and function made his designs particularly popular among consumers. In 1966, Harrison modernized one of life’s most notorious chores — taking out the trash — by replacing noisy metal trash cans with plastic, an innovation of the time.

“When that can hit the market, it did so with the biggest bang you never heard,” Harrison writes. “Everyone was using it, but few people paid close attention to it.”

Throughout his career, he concentrated on the importance of the ordinary, contributing significant updates to items like sewing machines, blenders and hairdryers. Harrison’s approach as a designer is based on what he calls ‘honest design’, which means refraining from adding extra or unnecessary features that do nothing to ensure durability or longevity. As former vice president of Sears Bob Johnson said of his designs, “If you look at his products, there’s really nothing superfluous about them.”

Though he enjoyed a long and fruitful career at Sears, Harrison was turned away when he first applied in the 1950s as a result of systemic racism. It was so prominent that initially getting hired there required working around the company’s informal policy of not hiring black people. Before Sears, one of Harrison’s former professors, Henry P. Glass set out to help find him work. This resulted in Harrison’s position at design firm Robert Podall Associates, where he went on to make his first notable design — updating the popular visual experience toy View-Master. Eventually recognizing his talent, Sears brought him on as a freelancer in 1961, and the rest is history.

Though he enjoyed a long and fruitful career at Sears, Harrison was turned away when he first applied in the 1950s as a result of systemic racism. It was so prominent that initially getting hired there required working around the company’s informal policy of not hiring black people. Before Sears, one of Harrison’s former professors, Henry P. Glass set out to help find him work. This resulted in Harrison’s position at design firm Robert Podall Associates, where he went on to make his first notable design — updating the popular visual experience toy View-Master. Eventually recognizing his talent, Sears brought him on as a freelancer in 1961, and the rest is history.

In observing his success as a designer, it’s imperative to mention the additional struggles he faced as a black male in the South. Growing up in segregated rural neighborhoods in Louisiana and Texas, racial oppression and division was apparent to Harrison from a young age. He shares his experiences growing up in all African-American neighbourhoods where integration with white people was a rarity.

“We were all African-Americans, so there was no segregation. We saw white people only when they came to the hospital or brought us deliveries.”

He went on to attend George Washington Carver High School, an all-black high school that closed when integration laws passed in the 1950s. Keeping in mind the social and cultural landscape in which he was raised, his rise to prominence in a white-dominated field is groundbreaking. As he reflects on his quiet and impactful trash can design, his desire to improve life for those who interact with his work is clear.

“As an industrial designer especially, your audience is neither history nor fame, but a couple who worked hard to buy their first home on a quiet street and would love just one more hour of sleep in the morning, even on trash day.”

With more than just consideration for the average homeowner, Harrison was also concerned with sustainability and environmental impact. His trash cans were designed with space-saving measures in mind, accounting for shipping, warehousing and finally utilizing them in homes. Harrison’s designs appear throughout the home, with improved power tools, kitchen appliances, toys, televisions, and radios.

Photo courtesy of Evanston Photographic Studios.

His breadth of knowledge around product design totaled over 700 products during his career with Sears, until his retirement in 1993. Since then, he has gone on to share his invaluable design knowledge as a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and at Columbia College Chicago. In 2008, Harrison became the first African-American designer awarded the Lifetime Achievement National Design Award by Cooper Hewitt, firmly cementing his long-standing legacy as one of America’s great industrial designers.

In an interview with the Smithsonian, Harrison adds this simple, resonating remark on the impact of design: “What designers do will affect so many people.” For a designer whose work continues to be seen in nearly every American home, there doesn’t exist a more relevant statement.

Purchase “A Life’s Design: The Life And Work of Industrial Designer Charles Harrison” online at Amazon.com or pick it up today at your local bookstore.